Watery Habitats

11/16/2023 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Saving the Cape Fear shiner, oyster farms, saving seabirds and a NASA water study.

Learn why NC organizations have partnered to protect a tiny fish, the Cape Fear shiner; how oyster farms impact estuarine habitats; and why scientists are trying to save fledgling oystercatchers from ghost crabs. Also, a UNC professor talks about his role in a NASA project measuring how much water is on Earth.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

SCI NC is a local public television program presented by PBS NC

Sci NC is supported by a generous bequest gift from Dan Carrigan and the Gaia Earth-Balance Endowment through the Gaston Community Foundation.

Watery Habitats

11/16/2023 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Learn why NC organizations have partnered to protect a tiny fish, the Cape Fear shiner; how oyster farms impact estuarine habitats; and why scientists are trying to save fledgling oystercatchers from ghost crabs. Also, a UNC professor talks about his role in a NASA project measuring how much water is on Earth.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch SCI NC

SCI NC is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Hi there, I'm Frank Graff.

How do oyster farms affect coastal habitats, restoring an endangered fish to a major North Carolina River, and just how much water on earth is there?

Get your swimsuits, we're diving into watery habitats next on Sci NC.

- [Announcer] Quality public television is made possible through the financial contributions of viewers like you who invite you to join them in supporting PBS NC.

- [Announcer] Funding for Sci NC is provided by the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

[upbeat music] [upbeat music continues] - Hi again, and welcome to Sci NC.

The Cape Fear Shiner is a fish that's only about that big, but it's an important indicator of the health of the Cape Fear River Basin.

The fish is endangered, but scientists are bringing it back.

Producer Michelle Lokter shows us how.

- I'm out on the Cape Fear River.

Somewhere in the water under this boat, there's a tiny little fish called the Cape Fear Shiner.

It's actually endangered, and scientists are working to help boost populations.

The Cape Fear Shiner is endemic to the Cape Fear River Basin, meaning it's the only place in the world where they live.

So that's where scientists like Brena go to collect and study them.

Cool, we can see the river.

Is this the Deep River?

- [Brena] Yeah, so this is the Deep River running along here.

And what you can see coming in right there is the Rocky River.

- [Michelle] All right, let's get down there.

Besides the hike into the river, it's not always easy to find these tiny fish.

- It's really challenging because you kind of have to learn what feels shiner-y, so to speak.

And this is the type of habitat that they really like.

These rocky areas with scattered pools, there's some riffle areas, some little runs.

They'll find an area behind a rock where it's kind of sheltered, and they don't have to work very hard.

And they'll hang out there, wait for some tasty food items to go by, jump out and grab it, and then go back and hang out in their little resting area.

- [Michelle] There are several types of shiners in these rivers, but Cape Fear Shiners stand out, sometimes literally.

- It's a small shiner that gets maybe about that big maximum size.

They are a little silvery fish with a dark stripe down its side, but then when they're in their breeding colors, they turn brilliant gold and yellow.

And they're really amazing looking fish, like things you only think of on a tropical reef or something.

But there's all kinds of species like that in our rivers in our backyards.

- [Michelle] But it's not just what's on the outside that counts.

Compared to other shiner species, they have extra long intestines that allow them to digest both insects and plants.

- That probably gives them the ability to be a little more adaptable.

These rivers are really changeable in terms of water levels and the types of conditions, so that would be an advantage to them.

- [Michelle] Despite this advantage, their numbers are small.

Human history in this river basin has impacted today's populations, and their future within this ecosystem is threatened.

The Cape Fear River Basin spans the fall line, a geological line of erosion between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain.

Rivers that flow over this drop in elevation have been used in the past as a source of energy.

- So there are lots of little old hydropower dams scattered throughout this area.

During that time period, one, there was lots of effluent and chemicals going into the river from mills and other industrial efforts.

And also dams created barriers for a lot of aquatic species like fish and crayfish, preventing them from moving between their habitats like they would have.

- [Michelle] Not being able to move between different parts of the river to mix with other populations decreases genetic diversity, which makes the whole population more vulnerable.

- Just by nature of being an endemic species that's only found in one place, if something were to happen, say we had a big chemical spill upstream in the Deep River that flowed down, this species is really open, really vulnerable to being just wiped out by one event.

So that's one of the reasons why we want to try to bolster the populations in the Cape Fear and the Haw.

So if something like that were to happen, or even if there was a big storm event and they weren't able to deal with that very well, we would have those other populations to provide what the service calls redundancy.

- [Michelle] In order to create this redundancy, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission partners with other organizations to catch adult Cape Fear Shiners and bring them to the National Fish Hatchery on the coast in Edenton.

It's open to visitors and there's an aquarium on site where you can see some of the other species they've worked with since the hatchery was established in 1898.

- Since then, we've produced about 12 different species and literally millions of fish from this facility.

- [Michelle] The hatchery was created to work with fish like American shad and Atlantic striped bass, but they've started working with non-food fish species like shiners and even gopher frogs.

- We are definitely moving into more conservation of endangered species and threatened species.

I think we are all recognizing that there's more work to be done to help these guys out.

And so we just wanna be a part of it.

- [Michelle] The Cape Fear Shiner is a recent addition to the hatchery, and Brandi is in charge of rearing these precious, shiny babies.

Starting with a new species, it's like whole new, again.

- Yeah, you have like a clean slate and it's challenging.

- [Michelle] Figuring out how to successfully breed a wild species in captivity takes trial and error, and they've gotten creative about how to make them feel right at home.

This is meant to simulate where they would nest in the wild?

- Correct.

They will spawn over slow moving pools with gravel, cobble and all, and they do enjoy vegetation.

So our vegetation is yarn, green yarn.

We glued some rocks around this Tupperware, and there's a quarter inch mesh so the eggs can just drop right in, and we can easily pull out and collect.

- People say that scientists aren't artists, that they're not creative, but I think this is evidence that's not true.

- Very true.

- [Michelle] They check the nests for tiny transparent eggs every morning.

- See the two right there?

- [Michelle] Yeah.

There's little baby Cape Fear Shiners, future shiners.

- [Brandi] But that's the beginning.

- [Michelle] The hatchery team raises this new generation of fish until the fall, and then they release them back into rivers in the Cape Fear River Basin.

[gentle music] The project started in 2020, and the first few years didn't yield many new fish, but once the setup was dialed in, they started to see results.

- We went from 0 to 517 fish released into the wild last year.

That's just science, you know?

Working with nature is you're always learning, you're always learning.

- This little fish, it's tiny, it might seem kind of insignificant.

Is it an indicator species of the health of these river systems?

- Yeah, so all of our aquatic species are basically serving the purpose of, you know, what we traditionally think of canaries in a coal mine.

They're indicators, they live in our water supply, breathe in it, eat in it, try to survive in it.

So if they're in trouble, that tells us that our communities are in trouble too.

But vice versa, if we have rivers that can support healthy native communities, diverse species, that means they can support our communities too.

So it's really important to pay attention to these animals.

- [Brandi] They're special, they're special to our state, and I mean, we don't wanna lose them.

It's somewhat of our prize possessions.

- Still in the water but now to the coast.

There are more than 220 oyster farms along North Carolina's coast.

It is a $30 million industry.

The farms are in public waters leased from the state, but until now nobody was first certain what effect those farms had on coastal ecosystems.

[gentle music] - A lot of people, they don't really know what a oyster farm is.

You know, sometimes people ask me, do I grow oysters in Durham, or, you know, do I grow oysters where I live in New Bern?

So people don't know that an oyster farm is just a, it's a lease, it's a part of the water that you just, you know, lease from the state that's out here with all the wild oysters.

- [Frank] This story is not just about oyster farms.

- Oyster culture industry nationwide has been growing really fast, and it looks like it's gonna continue to grow.

It's a really important source of aquaculture, local seafood.

- [Frank] It's about measuring change.

- Essentially, when you put these oyster farms in, you're transforming the estuarine landscape to some extent.

You're taking area of the estuary, which is important for natural resources, and you're converting it into a mariculture operation.

- [Frank] But the effects of oyster farms on fish habitat isn't known.

- [Jim] Do the fish like it?

You know, does it destroy the habitat?

You know, what are the costs and benefits of it?

- [Frank] Researchers wanna know how oyster farms are changing North Carolina's estuary coast.

- You're taking what is probably a semi featureless bottom.

Most oyster leases are on muddy bottom, sandy bottom, and you're putting in your oyster bags, right?

All these pilings, you're putting in ropes, you're putting in buoys, right?

So you're adding huge amount of structure to that area, right?

And so clearly, you know, fish are gonna act differently in a highly structured environment than the way they would act on just empty bottom.

- [Frank] So this is also a story about how scientists got creative to answer an important question.

- The initial project that we did was build our own miniature oyster farms.

And measure them continually over the course of four years and record how many fish are in these areas.

We recorded fish abundance before we put these oyster farms in, and then we continued to monitor them for three more years to see how the fish abundance has changed over time.

- So this is an Aris and this is an acoustic imaging system.

So basically, what it allows us to do is it shoots sound, right, kind of like an array, a beam coming out of here of sound into the water.

And what we were able to get from that is essentially like a video of what's in the water column.

- We can sample, you know, across an oyster farm and look right past all of the oyster gear and not have to worry about entangling nets and things like that.

Additionally, it allows us to watch the movements and the behaviors of the fish without interrupting them with fishing gear.

So we get an idea of the natural behavior of fish on oyster farms using this technology.

And we had one of our technicians basically pretend to be the oyster farmer, flip the bag and shake it, and we would record with a sonar in real time.

And a lot of times it was just a swarm of fish because when you disrupt the oysters, a lot of these, you know, small crustaceans and particles are showering off of the oysters and the fish are just gobbling it all up.

We find that the abundances of fish are about twice as high on oyster farms as compared to a nearby on, you know, tampered control habitat.

- [Frank] North Carolina has strict rules about where oyster farms can be located.

For example, oyster aquaculture can't be located in seagrass meadows.

But there's also the question of what the fish are doing on the farm and how the farm is connected to the surrounding habitat.

- To address that question, we did a tagging study.

We used acoustic transmitter tags.

We tagged about 30 fish, and we tracked their movements on a minute-by-minute basis.

- [Frank] Researchers captured and tagged sheepshead, a fish that lives around structures such as docks, or in this case oyster farms.

Tiny electronic tags were surgically implanted in the fish.

After recovery, the fish were released back into the estuary.

- So we had nine transmitters just like this kind of surrounding the farm.

And then we had a bunch that were sort of farther placed away.

Each of these transmitters pick up the pings from those acoustic tags, and each fish has a unique tag, so the actual acoustic signal it sends out is unique for each fish so we can identify the individuals.

And based on the difference in when each receiver picks up that signal, we can actually triangulate the exact location of each fish each minute.

So we can track the fish on a meter by meter scale as it moves through this area.

- [Frank] And it turns out the oyster reefs and surrounding estuary became one giant habitat for the fish.

The population appears to thrive.

- They're not just kind of showing up and leaving quickly.

They're staying in the area, and they're using surrounding habitats, and then coming back to the farm.

- [Frank] And then there was the aha moment.

- Soon as the sun sets, right, they basically stop moving, they come back to the oyster lease or some associated structure, and they basically stop pretty much all night long.

And then sunrise, they all start moving again, right?

And I mean like all perfectly in sync, right?

They're all sitting completely still.

Sun comes up and they're all just like all over the place.

- [Frank] So the fish are sleeping, do fish sleep, I guess?

- Yeah, and so that's like an interesting question, but I think you can at least assume that they're resting, right?

And that they're resting on the oyster lease because it's a good place of refuge, right?

- [Frank] Or they're watching TV and streaming something.

- [Andrew] Yeah, or hanging out, yeah, watching Netflix.

- Step to the water's edge, and you'll witness an interesting conflict between the oystercatcher, a bird, and ghost crabs.

Producer Rossie Izlar on why scientists are watching that encounter closely.

[upbeat music] - [Rossie] This is what the commute looks like for a coastal biologist off the coast of North Carolina.

- See the taller dunes with the vegetation?

When we get there, kind of just come through following our footprints, okay?

- It feels like a spy operation.

- It may have gone, it may have somehow gotten out of here.

- [Rossie] These bird nerds from Audubon are trying to find and band an oystercatcher chick here at Lea-Hutaff Island off the coast of North Carolina.

- It's really difficult to tell individual birds apart, but when you band a bird and give it something identifiable, it suddenly becomes an individual.

And for scientists, it helps us learn about their demographics, their movements, parameters that help us to understand how they're doing and what we might be able to do to conserve them, protect them, make sure that they're doing well.

- [Rossie] Oystercatchers look a little bit like a bird version of a clown, and they're a beloved shorebird that serves as a bellwether for other species.

- What's affecting the oystercatcher is probably affecting the least terns and the Wilson's plovers and the common terns and the black skimmers that are out here as well.

So we focus our efforts on monitoring them.

- [Rossie] But in order to monitor them, they have to find them.

- My sense is that maybe it's not in this clump of vegetation.

It does happen that, you know, you have to come back out and try again.

Oh, Kimmy, Kimmy, Kimmy, look, it's right here.

It's literally right here.

- That's the chick!

- It was just right there the whole time?

- It was right there the whole time.

- [Rossie] oystercatchers are unusual in that they're one of the few positive stories about birds right now.

- [Lindsay] So we're gonna go band them and give them back to his parents.

- [Rossie] Globally, shorebirds are on the decline.

Many species have lost more than 50% of their populations over the last three decades.

Oystercatchers were on the same trajectory, but after years of targeted conservation, the oystercatcher population has increased by 23%.

- [Lindsay] It turns out that if you focus your management on a species, work to improve their productivity during the breeding season, try to protect their roosting sites in the non-breeding season, it turns out that you can turn their trajectory around.

- Here's the thing, oystercatchers and other shorebirds breed in the same areas that humans and their dogs like to play, barrier islands.

Crucially, they lay their eggs among the dunes, completely exposed to the heat.

The parents shield the eggs from the sun with their bodies.

And when humans or dogs scare the parents away, that egg can literally cook.

- So 10 or 15 minutes exposed without the care of the parent can spell doom for them.

And that's why disturbance, people often say, "Oh, well I know what the eggs look like, I'm not gonna step on them."

It's like, yes, but you've separated the parents from the eggs of the chicks, and when the parents are separated from their young, just like we feel when we lose our kids at the mall, or we're not sure where our kids are, we're very nervous and because bad things could happen to them.

They need us to look out for them, and these guys need their parents to look out for them as well.

- [Rossie] That's why Audubon uses fencing to prevent people from stomping all over these dunes.

But they're also intentionally removing another threat to these birds, ghost crabs.

- [Lindsay] Oystercatcher chicks are not very big, and a ghost crab can kill them with a single blow from its claw.

- [Rossie] Oystercatchers have high sight fidelity, meaning they often return to the same spots year after year to raise their young.

That's why Audubon's Anna Cheshire traps ghost crabs in those spots and puts them somewhere else while the birds are too young to defend themselves.

- So you have to have enough of an angle that they can climb in, and then they get to the end of the tube, and then they drop into the bottom, and then they can't get back into the tube to go back in.

- [Rossie] So this is a lot of management, protecting land, fencing off dunes, manually removing ghost crabs.

We asked the team what keeps them motivated to do this work.

- I'm in it for the money.

[laughing] - I want everyone to be able to like be like, "Oh yeah, when I was young they had all these birds and I want when their kids grow up to be like, 'Yeah, I had these birds too.'"

And, no, I mean, I love this work.

I love looking at the chicks and seeing my nest, and it's always something new.

- [Lindsay] They're just part of what makes our planet, our planet.

It just seems like it would be a pretty poor place if this was quiet, like if we weren't sitting here listening to the least terns and hearing the occasional willet or the common nighthawk.

It would be a much poorer place if we didn't have them around.

- All right, little guy, go live your best life.

- Now to the really big question.

In a program focused on watery habitats, you gotta ask just how much water is there on earth.

Producer Evan Howell explains.

[energetic music] - [Pavelsky] Water is fundamental to everything that we do as a society, as a planet.

- [Evan] Most people would agree with Dr. Tamlin Pavelsky water is important.

We need it to drink, we need it for food, and we need to know when it just might be a threat to us and where we live.

- But surprisingly, we don't know very well how much water we have in different parts of the world.

And maybe just as importantly, we don't know how that's changing.

- [Speaker] Two, one, engine ignition, and the liftoff.

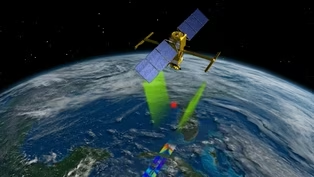

Liftoff of SWOT, our first global- - [Evan] In December of 2022, NASA, in partnership with the French Space Agency CNES and other nations, launched a satellite to answer that basic question about water.

It's called the surface water and ocean topography mission, or SWOT.

For three and a half years, SWOT will measure all the water on the planet.

- [Pavelsky] SWOT is gonna give us a completely new picture of where the world's water is and how it changes over time.

- [Evan] To find out how much water there is on earth, SWOT will measure its topography.

That's right.

It's gonna study the height of those bodies of water.

And scientists don't have a full understanding of how much water is flowing or where it's going.

And it's not just rivers and lakes, it turns out the ocean has topography too.

- There are places in the ocean that are a little bit higher, places that are a little bit lower, and that actually has a lot to do with ocean currents.

So for example, here in North Carolina we have the Gulf Stream offshore, and you can have a difference in elevation easily of a meter from one side of the Gulf Stream to the other side of the Gulf Stream.

That's ocean topography that we can hopefully detect from space.

- [Evan] For the mission to succeed, SWOT must take lots of very precise pictures.

That's a challenge.

Pavelsky says the measurements on the satellite must be just as exact as those on the ground.

- [Pavelsky] So SWOT, it's a radar satellite mission.

So it's sending radar waves down from space, bouncing them off of the earth, measuring how much comes back and how long it takes to come back.

And that in combination can tell us the topography of all of the world's surface water.

- [Evan] He and other scientists have been validating data since launch, measuring water height on the ground in spots like New Zealand.

- [Pavelsky] Over a certain area of river, we have to have a certain accuracy in terms of the elevation of the water surface, in terms of how well we measure that.

And that accuracy is 10 centimeters, right?

So that's on the order of four inches.

What we have to do is we have to go into the field and use really high precision GPS equipment to make those same kinds of measurements.

- [Evan] You could say Pavelsky started preparing for the SWOT mission as a child.

He grew up just north of the Denali National Park in Alaska with no electricity, running water, or even a phone.

He says he had an acute awareness for change, particularly in Arctic rivers.

So he went to school to learn about it and found SWOT.

- I went to my first meeting about SWOT in 2004 when I was a graduate student.

So from 2004 to 2022, that's 18 years, so this is almost like raising a kid.

And then we, you know, rather than sending it off to college, we send it off to space and, you know, please, phone home, please send data.

- [Evan] Pavelsky says SWOT is the most advanced satellite of its kind.

And when the mission is completed, SWOT will have measured the water height of around 6 million bodies of water on the planet.

But it's not just about telling how much water we have.

Data from SWOT will be able to tell us about hazards as well, like flooding, easily the deadliest natural disaster we have.

- [Pavelsky] We want to do a good job of being able to understand where we have flooding, how much flooding we have, how deep it is, and do a better job of predicting the future.

We need to have exactly the kind of data that SWOT is gonna provide.

- [Reporter] More than 17,000 people are being evacuated in the region.

- [Evan] SWOT got its first test in early June of 2023 when news outlets worldwide were reporting on the sudden failure of a major dam in southern Ukraine.

It had just unleashed flood waters, inundating large swaths of urban and rural areas.

Darker purple colors mean lower elevation, yellow and green mean higher.

- [Pavelsky] In early June of 2023 the Kakhovka Dam, which is a big dam on the Dnieper River in Ukraine, collapsed catastrophically.

We were lucky enough that the SWOT satellite was passing over this area every day during this time period.

And so we actually captured what this river looked like beforehand and then what the flood wave looked like on multiple different times.

This is an image from June 4th, which was before.

You can see that the river is relatively flat, and there's definitely some wetlands.

A few days after the dam broke on June 8th, it looks pretty different.

You can really see a lot of the flooding going on here.

These green colors are about 5 to 10 meters higher.

- [Evan] A new United Nations report points to the importance of SWOT.

The study shows one quarter of the world's population lack access to safe drinking water and nearly half don't have access to basic sanitation.

Pavelsky hopes SWOT can make a difference.

- [Pavelsky] We depend on it for drinking, we depend on it for irrigating agriculture, we depend on it to keep our ecosystems healthy.

Satellite data has been so incredibly important in making discoveries about our planet.

- And that's Sci NC for this week.

I'm Frank Graff, thanks for watching.

[upbeat music] [upbeat music continues] [upbeat music continues] - [Announcer] Funding for Sci NC is provided by the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

- [Announcer] Quality public television is made possible through the financial contributions of viewers like you who invite you to join them in supporting PBS NC.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 11/16/2023 | 20s | Saving the Cape Fear shiner, oyster farms, saving seabirds and a NASA water study. (20s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

Support for PBS provided by:

SCI NC is a local public television program presented by PBS NC

Sci NC is supported by a generous bequest gift from Dan Carrigan and the Gaia Earth-Balance Endowment through the Gaston Community Foundation.