The Rise and Fall of the Asylum

Episode 3 | 54mVideo has Closed Captions

The fascinating story behind the rise and fall of the mental asylum in the United States.

Until a few decades ago, the United States relied on mass confinement in mental asylums, for the mentally ill, as well as extreme treatments, from lobotomy to coma therapy. Today, at Cook County Jail in Chicago, more than one-third of inmates have a mental health diagnosis. Meet the detainees whose lives hang in the balance and discover the harsh realities of care both in and out of jail.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for Mysteries of Mental Illness is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Johnson & Johnson, the American Psychiatric Association Foundation, and Draper, and through the support of PBS viewers.

The Rise and Fall of the Asylum

Episode 3 | 54mVideo has Closed Captions

Until a few decades ago, the United States relied on mass confinement in mental asylums, for the mentally ill, as well as extreme treatments, from lobotomy to coma therapy. Today, at Cook County Jail in Chicago, more than one-third of inmates have a mental health diagnosis. Meet the detainees whose lives hang in the balance and discover the harsh realities of care both in and out of jail.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Mysteries of Mental Illness

Mysteries of Mental Illness is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Join the Campaign

Share your story of dealing with mental illness through textual commentary, a still image, a short-form video — however you feel most comfortable — using the hashtag #MentalHealthPBS on social media.♪ (indistinct chatter) CATHRYN JOHNSON: What were you diagnosed as having?

JEREMIAH ROBINSON: Anxiety... JOHNSON: Mm-hmm.

ROBINSON: PTSD.

JOHNSON: Mm-hmm.

ROBINSON: Depression, bipolar, and schizophrenia.

JOHNSON: Wow.

ROBINSON: I've been in state penitentiary two times.

And I've been locked up in here, in Cook County, I can't even count how many times.

Not too long ago, I was diagnosed with all those different type of illnesses.

I really didn't buy it at first because I was just thinking, like, maybe the feeling that I was having was more, like, from me being incarcerated.

And when a psychiatrist was asking me personal questions like, what I've been exposed to, what type of drugs I was using, like, how many people I know had been murdered...

They were explaining to me that those are the reasons that I probably have the illnesses that I have today.

When I don't medicate, I don't be in my right state of mind.

So it's like, you know, having that good angel and that bad angel on your shoulder.

I wonder, like, where does it come from?

I don't even know where to find help out there in the world.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Mental illness is rife with mysteries.

After centuries of searching, there are still no reliable cures.

and even diagnoses change over time.

The one constant; those labeled mentally ill have always faced stigma.

♪ ASHWIN VASAN: Stigma is about otherizing people that are different to yourself.

We've done that from time immemorium for people with mental illness.

We have never seen them as fully human, and therefore fully deserving of all of the menu of rights of a human being.

And so the systems we have are simply a result of that.

♪ (bird squawking) NARRATOR: Today, America's largest mental health facilities aren't hospitals, they're jails.

TOM DART: When I first became sheriff here in Cook County, I honestly didn't truly understand what I was getting myself into.

INTAKE SCREENER: Have you ever been diagnosed with any mental illnesses or any mental health issues?

Bipolar 1 disorder.

INTAKE SCREENER: When you felt depressed, has it lasted every day, for two weeks, or longer?

- Give or take.

- Give or take?

- Yeah.

INTAKE SCREENER: What diagnosis qualified you for that care?

- Bipolar.

- Okay... - Interpersonality disorder.

- Okay.

DART: Entire divisions were filled with people who were mentally ill. Our population pretty consistently is 40% with a diagnosed mental illness.

(indistinct chatter, cell door creaking) NARRATOR: About 50,000 people pass through Chicago's Cook County jail each year.

Over 90% are people are color.

♪ SIDNEY HANKERSON: As a result of institutionalized racism, and the legacy of mass incarceration in this country, we know that Black men with mental health problems are more likely to be brought in by police compared to white men.

Now there is an increased awareness of the racial injustice that our country is facing, and the field of psychiatry is at the center of this reckoning.

♪ NARRATOR: Like many here, Jeremiah Robinson grew up on the south side of Chicago.

ROBINSON: It was a pretty okay neighborhood for me, but as I got a little older, it started to be a little bit dysfunctional.

♪ A lot of drug dealing, people getting hurt, violence.

I was an A and B student.

But I kind of messed up a little bit in high school.

I was fighting a lot.

NARRATOR: In high school, Jeremiah was twice referred to a mental hospital.

ROBINSON: They figured that I had a behavior problem, but I didn't realize that I was having a mental problem.

(people speaking indistinctly) NARRATOR: Jeremiah is awaiting trial for parole violation and weapons possession.

This is his 15th arrest.

Past charges include drunk driving and drug possession.

ROBINSON: I definitely know that there's, there's some type of problem that's affecting me.

(people speaking indistinctly) NARRATOR: Jail and prison psychiatrists diagnosed him with schizophrenia, anxiety, bipolar, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

ROBINSON: This, this picture right here, it's like of my daughter, it's just a off-the-head type of sketch.

I ain't finish it up though, I just, kind of get a little... My anxiety kick in a little bit and, you know, and I don't want to...

I tend to, like I say, I can't stay focused on one thing for too long, so I wind up doing something else.

So that's why I didn't complete the drawing though.

♪ JOHNSON: I kind of think of the jail as almost the emergency room; here's where we stabilize you, right?

So you're going to need some long-term care after you're stabilized.

There isn't any one place that we can send them to, to make sure that they're cared about once they leave the jail.

It just doesn't exist anymore.

♪ NARRATOR: How did this happen?

How did prisons and jails become a front-line treatment for the mentally ill?

♪ "What to do with the mentally ill?"

is not a new question.

Cures have always been elusive, and societies have often viewed those living with mental illness as a burden and treated them as disposable.

For centuries, families paid to confine relatives to "madhouses" which provided shelter but little treatment, while prisons and hospitals-- like the infamous Bedlam in England-- locked them in cells.

GEORGE MAKARI: Bedlam was a tourist attraction.

Patients were gawked at.

They were treated in deeply inhumane ways-- as deviants, and morally deficient.

Essentially like they're criminals.

NARRATOR: The line between treatment and punishment often blurred, with exorcisms, blood-letting, and even extreme mechanical devices.

ANDREW SCULL: They're two different moral universes.

One sees this as entirely appropriate, exactly what you need to do with violent madness.

And the other sees it as, as we might, as intolerable cruelty.

♪ NARRATOR: One American woman who found it intolerably cruel was schoolteacher Dorothea Dix.

ANNE HARRINGTON: Dorothea Dix was a very unlikely reformer.

She wasn't highly educated.

She was a woman in a time when women had very little, if any political power.

NARRATOR: In early 19th century Boston, Dix founded a school for girls.

She taught the poor for free.

But her own struggles with depression eventually led her to England and a new kind of treatment.

HARRINGTON: She made the acquaintance of Quakers.

They created the first alternative to the madhouses called the Tuke's Retreat, the place where benevolence as opposed to harsh treatment predominated.

SCULL: It's a very different kind of approach known as moral treatment, which tries to coax the madmen back into reality, tries to encourage his or her ability to control themselves rather than be externally coerced.

♪ NARRATOR: Inspired by this idea of "moral treatment," Dix returned to the U.S. She taught at a women's prison and saw mentally ill inmates chained to walls, in unheated cells.

Her outrage earned her the nickname "Angel of the Madhouses."

MATTHEW GAMBINO: She saw it as very much her moral mission to petition local legislatures, state legislatures, and ultimately the federal government to create facilities that drew from the United Kingdom, where patients would be treated as human, and would be brought into a small social order.

ROBERT KIRKBRIDE: But she was not permitted as a woman to debate or present her ideas.

It had to be men representing her arguments among other men.

NARRATOR: On June 27, 1848, Dix sent a proposal to Congress requesting a vast system of federally funded asylums.

It concluded: "May it not be demonstrated "as the soundest policy for the federal government "to assist in diminishing and arresting widespread miseries "which mar the face of society, and weaken the strength of communities?"

After much debate, the government rejected Dix's appeal for national reform.

(projector whirring) But many states were drawn to her compassionate approach.

RALPH DIDLAKE: Dorothea Dix visited Mississippi as she did many states, and she was successful in getting the Mississippi legislature to appropriate money to build an asylum.

And it was indeed, in 1855 when it opened, a state-of-the-art facility, a so-called Kirkbride structure, using what was then state-of-the-art care for the mentally ill. NARRATOR: Thomas Kirkbride-- a Quaker doctor-- laid out detailed plans that were the basis for the Mississippi asylum and many others across the country.

Dix embraced his belief architecture could support moral treatment.

Robert Kirkbride is Thomas' distant relative.

KIRKBRIDE: Kirkbride built these structures as places for people who had no other place.

These were castles that were built for those who are not aristocracy.

They were intended for people who were dispossessed.

MAKARI: The notion of asylum, of a retreat from the world, was not just, like, a place to rest.

It was a place to be cured.

The idea was if you had a curative environment, you could actually cure mental illness.

NARRATOR: The buildings had a distinctive bat wing formation.

KIRKBRIDE: The further you went out into the wings, the more extreme the cases became.

The cases that were the most likely to return soon to the world were closest to the central main administrative building, where often the superintendent lived.

NARRATOR: Kirkbride believed natural light encouraged healing, so there were large windows and high ceilings, wide hallways for socializing, and large rooms for occupational therapy.

KEITH WAILOO: Dorothea Dix and hospital reformers saw these institutions as places of moral order where the new regimens that could be created for the mentally ill were themselves therapeutic.

DIDLAKE: There was not a lot of specific treatments, certainly not pharmacological treatments, other than calming the patients, and occupational therapy, allowing them to walk on the grounds.

NARRATOR: Kirkbride's asylums were to be set off from the rest of society, so quiet and nature could calm the mind.

JEFFREY LIEBERMAN: Even the term that was used to describe the doctors who were responsible for these places, they were called alienists, because they were alien to society.

And people with mental illness were alien to society.

They existed in this other world.

♪ NARRATOR: The goal was to rehabilitate patients and send them back to society as productive citizens.

VASAN: The history of moral treatment is grounded in that intrinsic human truth, which is that people need things to do that are of their own choice in places where they feel safe and to build up experiences that help them overcome their disability, or at the very least, manage the disability that arises from chronic serious mental illness.

NARRATOR: Dix's call for compassionate care swept America.

But her utopian vision soon collided with harsh realities.

♪ Across the country, ruins are among the last remnants of these palaces for the dispossessed, designed to cure mental illness a century and a half ago.

♪ What happened to these places of healing?

KIRKBRIDE: Kirkbride was specific.

From the very beginning, he said 250 patients at a time in a state hospital, and do not go above that.

That almost immediately was outstripped.

♪ NARRATOR: Just as moral treatment took hold, the Civil War ravaged America.

♪ It siphoned resources and drove thousands of traumatized people to asylums like the one in Mississippi.

DIDLAKE: Like many institutions in the state, it suffered in the immediate postwar period.

There was overcrowding and under-resourcing.

And it was almost immediately overwhelmed by the need to care for the mentally ill. NARRATOR: After the war, in Mississippi's segregated wards, Black patients were often forced to sleep on the floor, and they died at twice the rate of whites.

♪ Over decades, some 30,000 patients came through.

Many never left.

The asylum's cemetery was only recently discovered.

♪ MOLLY ZUCKERMAN: In the fall of 2012, construction work was happening on the University of Mississippi Medical Center's campus.

And they stumbled upon a burial.

♪ In total, 68 human skeletons were excavated from the site.

So we used ground-penetrating radar to map out where burials might be in the remainder of the area.

We've estimated approximately 7,000 burials on the site.

There are no institutional records that allow us to determine with any certainty who is buried in what particular part of the cemetery.

NARRATOR: Of the 7,000 burials, not a single one has been identified.

(birds chirping) And there's no trace of the grand Kirkbride asylum that once stood here.

♪ But records in the state archives reveal why many were admitted and how many died.

LIDA GIBSON: You have to be careful with them.

ZUCKERMAN: Yes... Do you want to follow this one?

GIBSON: Yeah, sure so let's see who this is.

This would be... John Ross, and he was a farmer from Holmes County.

Chronic mania and then... ZUCKERMAN: Is the form of mental disorder?

GIBSON: Is the form of mental disorder.

ZUCKERMAN (voiceover): The assumption was that people would recover quickly and be able to be released.

GIBSON: Here's a dementia praecox, which is now called schizophrenia.

Epileptic mania, acute mania, recurrent mania, depressive mania.

ZUCKERMAN (voiceover): But there were extremely limited treatment options, so a lot of these people were going to be there for the rest of their lives.

GIBSON: Here's a man named Willis Barnes, and, my goodness, he had 20 kids.

And the reason he was admitted was worry.

NARRATOR: Hardships outside the asylum often led people to its doors.

And poor nutrition was one common culprit.

ZUCKERMAN: A lot of people who were involved in cash crop agriculture, so primarily cotton production, were not able to produce agricultural products on their farms that they could eat and instead they were dependent on what they could buy, which was primarily processed corn meal.

Those really protein-deficient diets resulted in pellagra, which is a vitamin B deficiency.

"Pellagral insanity."

GIBSON: Mm-hm.

ZUCKERMAN: Died from pellagra.

GIBSON: Huh.

NARRATOR: Pellagra could led to dementia, and was a common cause of admission and death.

ZUCKERMAN: Everybody on this page died of pellagra.

(voiceover): It wasn't known exactly what caused pellagra, and so it wasn't something that could be effectively treated.

GIBSON: So this is quite a run here.

We have, syphilis, syphilis, unknown, TB-- tuberculosis-- and syphilis.

NARRATOR: Nearly a quarter of asylum patients had syphilis-- the sexually transmitted bacterial disease-- a leading cause of psychosis.

GIBSON: Then their form of mental disorder is acute mania.

ZUCKERMAN (voiceover): The increase in cases of syphilis into the early 1900s is really, really dramatic.

And you would not have recovered from this disease.

So we have kind of burgeoning populations in all of these asylums and an inability to provide caretaking that is necessary for them.

GIBSON: Here's a teacher from Warren County, which is Vicksburg, and her form of mental disorder was nymphomania.

NARRATOR: Patients could be admitted if a family member merely claimed they were insane, and two physicians backed it up.

GIBSON: She was there for 11 years, six months, and 20 days, and then she died.

♪ WAILOO: The idea that people could die in institutions and just be buried there without any public accounting, without any public awareness, and that these stories could be unearthed many, many decades later highlights one of the fundamental problems with asylums.

People were literally out of sight, out of mind, and in many instances, forgotten.

(film music playing) FILM NARRATOR: Sanctuary, refuge, hospital-- this is no snake pit.

The doors are locked, but it's not a prison that we enter.

For these locks are meant to protect patients.

WAILOO: One of the major problems was that there was this sense that they were evolving outside of any public view, outside of any political oversight, and in a world by themselves.

The practices there were unaccountable.

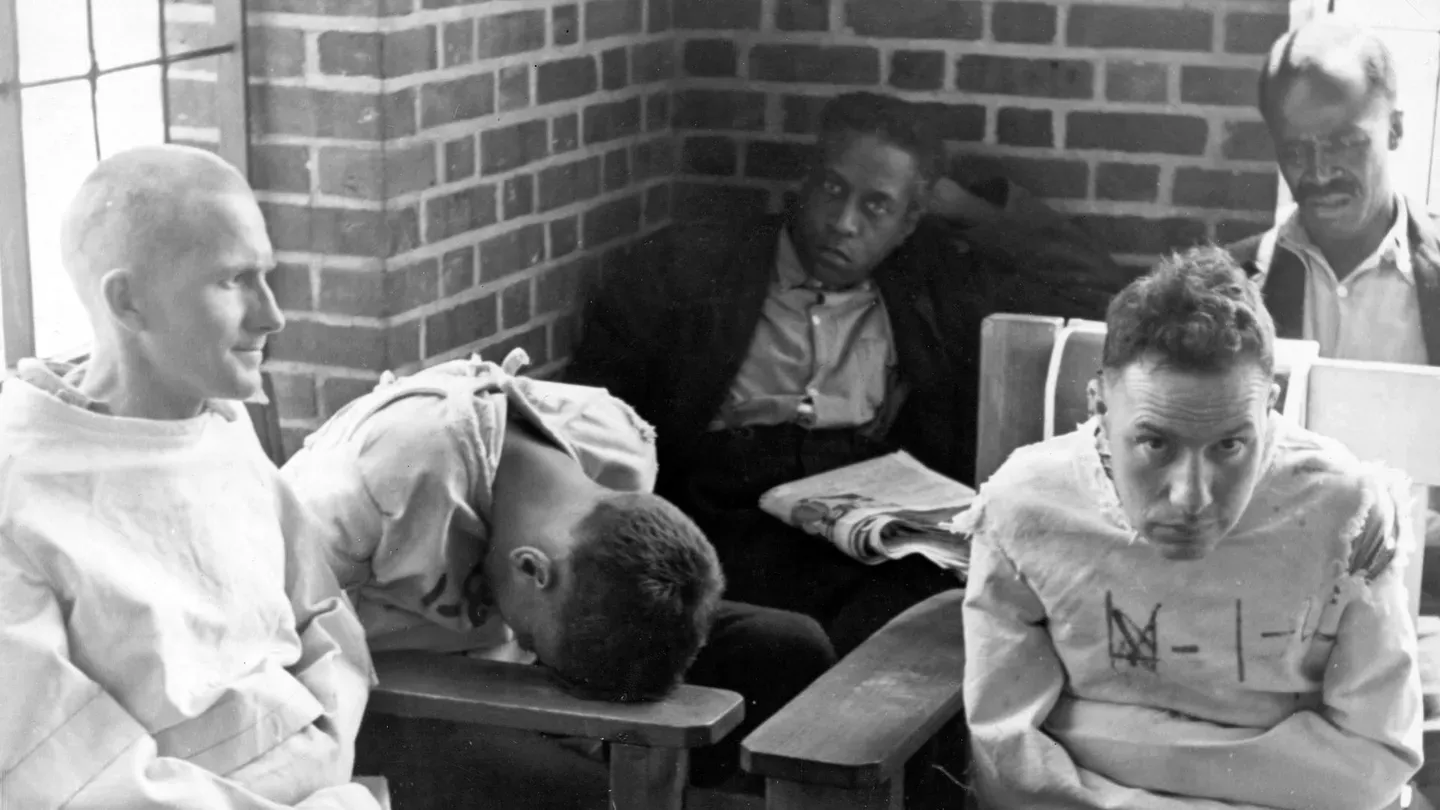

NARRATOR: By the early 20th century, asylums overflowed with patients.

Some Kirkbride facilities housed nearly ten times more than originally planned, with only one doctor for hundreds of residents.

♪ And these doctors understood little about how to cure mental illness.

LIEBERMAN: We didn't know very much about the brain, how it worked, and what happened to cause someone to become mentally ill.

I mean, we knew that the brain was an organ, and we knew it resided inside the skull, and we knew it was really an amalgam of many, many cells called neurons that were wired together.

But we didn't know how they fit together, we didn't know what functions they served.

And so, we could do nothing to really treat people with severe mental illness.

NARRATOR: To handle the ever-growing patient population, states expanded Kirkbride buildings and constructed new, giant asylums-- including the world's largest hospital of any kind-- "Pilgrim State" in Long Island, which held more than 13,000 patients.

Out of view from the public eye, desperate doctors experimented with new treatments.

SCULL: There are a lot of experimental therapies that now strike us as quite bizarre, even sadistic.

It's important to understand that the people doing these things were very often true believers in what they were doing.

They sincerely thought that their interventions were therapeutic... and well-motivated.

♪ LIEBERMAN: The treatments that were attempted were based on speculations.

And in most cases, they proved to be wrong.

♪ NARRATOR: In 1927, an Austrian doctor won a Nobel prize for his radical approach to treating patients with psychosis-- so-called "malaria therapy."

LIEBERMAN: He had observed that when patients in his asylum developed a fever, it often made them better.

So he thought, "If I induce a fever, this will be therapeutic."

So he would take the blood of malaria victims and inject it into mentally ill persons.

But he wasn't actually alleviating the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia, he was curing or improving people who had syphilis of the brain, and the high fever was killing the microorganism.

NARRATOR: While "malaria therapy" did help treat some psychoses caused by syphilis, the treatment didn't work for other ailments, and could be deadly.

SCULL: When they had to explain away the fact that they'd originally promised they'd cure all these people they put into asylums and then they couldn't, they said, "Well, really, "that was because they were biologically defective.

They weren't fully human, they were degenerates."

The language became extremely, extremely harsh.

GIBSON: "It is for the best interest of the patients "and of society, that any inmate of the institution "under his care should be sexually sterilized.

"Such superintendent is hereby authorized "to perform the operation of sterilization on any such patient confined in the institution."

DIDLAKE: In 1928, the Mississippi legislature passed a law allowing sterilization of the mentally ill without consent.

NARRATOR: Similar laws swept the nation, fueled by eugenics-- a theory that categorized both the mentally ill and the mentally deficient-- as inferior.

MAKARI: Eugenics is a kind of discipline that was founded by Francis Galton, who was related to Charles Darwin, where the idea was that the genetically feeble should in some way be winnowed out of the population.

♪ That was an idea that was favorable to both conservatives as well as progressives who really looked forward to a bright future.

♪ NARRATOR: Over decades, tens of thousands of men and women in state-run institutions were sterilized against their will-- often without their knowledge.

ANGELA COOMBS: You go in for a different procedure, you come out, and you're not able to reproduce.

So this was happening in the context of eugenics being looked at as some legitimate science, so that you could then justify not allowing people to reproduce.

(man in film speaking German) MAKARI: This eugenics program in the United States kind of looped back to Nazi Germany, where the Nazis oversaw the murder of over 200,000 psychiatric patients in what was considered to be a prelude to the murder of then the disabled, and then of course the Jews.

NARRATOR: Why were the ideals of moral treatment set forth by Dorothea Dix no longer upheld?

♪ While American eugenicists didn't go as far as the Nazis, psychiatrists were desperate to control the number of mentally ill. After World War II, asylums were reaching their peak, housing more than half a million patients.

MAKARI: The notion that these were curative places transformed into the notion that they were hellholes, that they were huge institutions that warehoused people.

SCULL: People condemned to the back wards of a mental hospital were going to be there for life.

And it was an almost inhuman existence.

So anything you might do that would rescue them was perhaps worth trying.

MAN: Six centimeters above the zygoma, in the coronal suture, the opening is made.

Turning now to the brain, the frontal lobe is bounded by the Sylvian fissure... NARRATOR: The workings of the brain remained mysterious, but after observing patients with head injuries or strokes, a theory emerged-- that damage to an area of the brain called the frontal lobe altered personality and behavior.

Some wondered, could surgically severing the frontal lobe cure mental illness and possibly even make asylums obsolete?

SCULL: The idea was that madness emerged because the frontal part of the brain, the most distinctively human part of the brain, had somehow gone awry.

And the connections between the front and the back of the brain had become twisted and distorted.

And if we could somehow interrupt some of them, we could interrupt the madness.

NARRATOR: In 1936, Washington, D.C., neurologist Walter Freeman performed the first lobotomy in the United States.

SCULL: It was widely seen as a kind of miraculous intervention in the course of psychosis.

There were some patients who were clearly damaged, but nonetheless had lost their obsessions and their involvement with hallucinations and delusions, and were able to function more or less, perhaps even be discharged from the hospital, as quite a number of them were.

Many of them became vaguely happy all the time.

And so, in the context, some people saw that as a trade-off worth making.

♪ There was a huge lobotomy program at Harvard, at Yale, at Columbia.

It spread everywhere.

NARRATOR: Even far outside the asylums.

In 1941, 23-year-old Rosemary Kennedy-- younger sister of future president John-- became one of Walter Freeman's patients.

Rosemary was developmentally challenged from birth.

HARRINGTON: She had been very carefully trained and kept on a very, very tight leash, but there was growing concern, particularly by Joseph Kennedy, the father, that Rosemary was starting to rebel.

She wanted to be like everyone else and have a life.

It was felt that, you know, she could end up pregnant.

And this would be a great embarrassment.

It was suggested to Joseph Kennedy to lobotomize her.

It would make her docile.

MAN: The first mark is made three centimeters behind the lateral rim of the orbit.

NARRATOR: Rosemary would be unable to walk or speak after her psychosurgery.

MAN: Another mark is made in the midline, 13 centimeters from the glabella.

NARRATOR: Her parents would send her to a privately run institution and keep the details of her procedure secret, even from her siblings.

MAN: Operations can be performed under local anesthesia if the patient is sufficiently cooperative.

ANDREA TONE: Women tended to be lobotomized more than men.

In part because husbands reported back saying how happy they are that their wife has been restored and will now do housework and leave their home cleaner than it ever was.

SCULL: Because each operation took an hour or two and involved a very scarce commodity, a neurosurgeon, well, you know, this was not good.

NARRATOR: So Freeman found a way to streamline the operation.

Instead of accessing the frontal lobe by drilling holes in the skull, he took a shortcut through the eye socket using a tool modeled after an icepick.

SCULL: That enabled lobotomy to be done very fast.

Most patients were confined in mental hospitals against their will.

When that happened, they lost their civil rights, they lost any access to the outside world.

Their wishes were considered to be the product of their psychosis.

So doctors certainly performed many lobotomies on patients who had no say whatsoever.

♪ NARRATOR: But by the early '50s, a new revolution would end the lobotomy craze and change asylums forever.

MAN: This real chance for many of us to get well again is due to research in mental illness.

And one of the most hopeful contributions of that research is new drugs.

It says over here you heard voices-- is that true?

- Yes.

- Hm?

ALLEN FRANCES: All of the drugs in psychiatry were discovered serendipitously by accidental clever clinical observation.

SALLY: This is me when I came to the hospital.

I was very upset from many worries.

- What did the voices say to you, Sally?

(unintelligible) FRANCES: Thorazine, the first antipsychotic, was discovered because it was being used by surgeons as an antiemetic, so people wouldn't throw up during operations, and it calmed the patients down.

SALLY: This is me after the doctor gave me some medicine to help me.

DOCTOR: And you were telling me there was something wrong with the neighborhood, is that right?

- Mm-hmm.

Now I'm not so mixed up.

I talk to him okay.

LIEBERMAN: There's no question that in the scope of history, when it comes to understanding mental illness, the real turning point came with the introduction of Thorazine.

NARRATOR: The effects of these drugs on Sally and patients like her led scientists to a new theory: that antipsychotics alter levels of a chemical in the brain called dopamine.

Dopamine was one of dozens of neurotransmitters discovered over time.

LIEBERMAN: In identifying these, seeing what parts of the brain those were operative in, we developed drugs and used them to treat various types of neuropsychiatric conditions.

NARRATOR: To this day, how exactly changes in brain chemistry lead to changes in thought and behavior remains unknown, but in the 1950s, antipsychotics let asylums do the unthinkable: send patients home.

DOCTOR: What's the difference?

- I feel like I talk just to myself.

I don't feel like talking to nobody else, just to myself.

Patients who were hitherto unmanageable or untreatable or who had resisted all other forms of treatment now have been helped.

SALLY: I am very happy to go home.

TONE: When Thorazine first came onto the market, it was advertised as a chemical lobotomy.

The idea that patients who may not have had much hope before could take a pill and be discharged from a hospital, it was quite miraculous.

NARRATOR: Antipsychotics had serious side effects, but almost immediately reduced the need for mass institutionalization just as it reached its height.

SUSANNAH CAHALAN: The height of the asylum population was about 1955.

And at that point, I think 550,000 people were, were hospitalized.

This was a major part of the fabric of society.

You probably knew multiple people who had been hospitalized.

NARRATOR: The advent of pharmaceuticals fueled deinstitutionalization.

But as patients left the asylum, they also left the institutional safety net Dix's moral treatment had provided.

GAMBINO: One of the things that we often overlook is how much agency patients themselves had about their lives and creating the world in which they lived.

They formed relationships.

They wrote institutional newspapers.

They found forms of self-expression in an otherwise impoverished and brutal environment.

MAN: But suddenly now, there is new hope for all.

For you, the public, who pay the bills, and for us, the mentally sick.

VASAN: People with serious mental illness who were leaving psychiatric hospitals said to themselves, "We need a place to go.

"No one really wants us.

"No one will employ us.

"Where can we go that's safe, "and actually rebuild our lives in some fashion, to whatever degree we can do that?"

NARRATOR: Patients and advocates worked to build a patchwork system of locally based community care.

Some leaders paid attention, and looked for alternatives to institutionalization.

MAN: ...John Fitzgerald Kennedy, do solemnly swear... KENNEDY: I, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, do solemnly swear... NARRATOR: When John F. Kennedy became president in 1961, he'd only recently learned about the disastrous outcome of his sister Rosemary's lobotomy.

FRANCES: Kennedy himself had a strong, I guess, guilt and desire to improve the life of the mentally ill in the country.

So help me God.

(applause and cheers) NARRATOR: Like Dorothea Dix more than a century before, he called for America to treat the mentally ill with greater compassion.

KENNEDY: The mentally ill and the mentally retarded need no longer be alien to our affections or beyond the help of our communities.

Under this legislation, custodial mental institutions will be replaced by therapeutic centers.

♪ NARRATOR: Congress passed the Community Mental Health Act of 1963 to fund the alternative programs patients and advocates had initiated.

This was Kennedy's last legislative victory.

He was assassinated three weeks later.

KENNEDY: I think that in years to come, that those who've been engaged in this enterprise can feel the greatest source of pride and satisfaction and that they will recognize that there were not many things that they did during their time in office which had more lasting imprint on the well-being and happiness of more people.

So I express all of our thanks to them, and I think it's a good job well done.

CAHALAN: In that speech, JFK saw a vision of the future where 50% of the population would no longer need to be hospitalized.

FRANCES: The promise was great.

It was an era of democratization.

The patients were very much involved.

We were not only going to be changing the world for the severely ill who were discharged, but we also had high hopes that we could help improve the whole mental health of the communities.

♪ NARRATOR: Then, in 1965, President Johnson signed Medicaid into law to cover medical costs for low-income Americans.

But psychiatric hospitals with more than 16 beds were not covered.

One goal was to steer money into community care and away from asylums.

♪ These castles, optimistically built to cure the mentally ill, hadn't fulfilled their promise, and opposition to them reached a crescendo.

DOCTOR: When were you admitted to the hospital?

WOMAN: It was about five weeks ago.

DOCTOR: And who actually brought you to the hospital?

My husband.

And six policemen in three police cars.

FRANCES: It began to be expressed that any form of involuntary hospital commitment was a crime of the state against individual liberty.

SCULL: And then came the Hollywood movie "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

Did Billy Bibbit leave the grounds of the hospital, gentlemen?

SCULL: Which really portrayed psychiatry in an extremely negative light.

I want an answer to my question.

SCULL: As fools or villains or both.

NARRATOR: The film captivated America in 1975, the same year the Supreme Court ruled the mentally ill could not be forcibly committed unless they posed a danger to "self or other."

WARREN BURGER: There is no constitutional basis for confining such persons involuntarily if they are dangerous to no one and can live safely in freedom.

NARRATOR: This landmark victory allowed patients to refuse care, but in many ways backfired.

♪ WAILOO: The deinstitutionalization movement was driven by a true and beneficent, progressive ideal for providing a better chance at life and health for people who had been locked away.

To the extent that many of those people were freed and have gone on to live full and complete lives, right?

Those were really progressive developments.

But this is difficult, because to refuse care also puts the onus on you to care for yourself.

And society has to figure out a way to deal with that.

NARRATOR: The 1970s brought new freedom for patients, but also a financial crisis that drove a conservative backlash against social programs.

WAILOO: The history of American mental healthcare is a history of liberal, expansive projects to provide progressive care, and recoiling against the costs and the nature of the social commitment.

CAHALAN: This dream of being treated in the community never came to fruition because the money did not follow the patients.

VASAN: You've got the federal government basically saying, "We're going to close down a system "that is pernicious and punitive and inhumane, "but we're not gonna make enough of a durable investment into communities."

RONALD REAGAN: We'll continue to search for ways to cut the size of government and reduce the amount of federal spending.

WAILOO: The Community Mental Health Act hits the rocks with the Reagan-era conservative revolution, which argues that, you know, government isn't the solution to your problem.

Government is the problem.

He took the money that had been allocated specifically for the mental patients in the community and instead gave them to the states as a block grant, which the state could use for the mentally ill, or use to reduce taxes, or increase other programs, and eventually to build prisons.

♪ NARRATOR: At the same time community care was defunded, money for prisons flowed.

And the treatment of the mentally ill began to resemble the punitive systems of the past.

MAN: ♪ Go tell it on the mountain (indistinct chatter) COOMBS: You have people being incarcerated at rates that are surpassing other nations during this time.

Such that you get the mass incarceration of folks with mental illness.

This is happening at the same time as mass incarceration of people of color.

So, if you have both a serious mental illness and you are a Black American, that risk of you being incarcerated is that much higher.

FRANCES: The irony was that the mentally ill were not really deinstitutionalized.

They wound up in nursing homes or in prisons, or homeless.

Next two gentlemen, step up.

CAHALAN: Today, 90% of the beds available with JFK's Community Care Act are no longer available.

As bad as many of these institutions were, I can't think of a worse place to be than a prison or a jail when you are acutely psychotic.

LIEBERMAN: States by and large have reduced the number of state hospitals they have and reduced the number of beds they have, and made it more difficult to admit people to.

MR. BO: Who's been diagnosed with PTSD?

Okay.

Depression?

Okay.

Anxiety?

Bipolar?

MAN: Yeah.

- Okay.

And schizophrenia?

VASAN: Black Americans are three times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, but only one out of three Black Americans actually get access to mental healthcare that they need once they receive a diagnosis.

Share-- will you share with me, my brother?

- Since I've been coming out of the jail system, I never had no type of help, no type of support or nothing, but... NARRATOR: Untreated, mental disorders can worsen, and those with mental illness are more likely to enter the criminal justice system.

Once there, they accumulate diagnoses.

They diagnosed me with bipolar and schizophrenia.

FRANCES: The more psychiatrists you meet, the more likely you are to get a new diagnosis.

Then it's so easy to write a diagnosis, so hard to erase it.

My mother for my father, to her mother and her father, this, they have bipolarness, PTSD, and anxiety.

DART: In the criminal justice system, we're supposed to incarcerate people because they present a danger to us and to society.

In grade school, like, I always had a short attention span.

I was always, like... DART: But I cannot tell you how many detainees said to me, "I just can't believe I had to go to a jail to have this help."

MR. BO: Mr. Robinson, I've been working with you for a while.

Can you share one of the diagnoses that maybe, that you struggle with the most?

- I would say the PTSD.

(voiceover): In a group session, it's kind of hard for me to expose myself like I can talk to you right now, in a one-on-one.

And if I'm in a more of a group, I don't really want the next person to know the type of problems that I'm having, you know?

I kind of feel ashamed of them.

Because I've been around certain type of environments and violence, been exposed to it, and...

It was just, it became the norm to me after just dealing with it for so long.

MR. BO: Thank you for sharing that, because so many men do the same thing.

NARRATOR: Jeremiah was diagnosed with several disorders, including PTSD and schizophrenia.

His most consistent mental health treatment has been in jail, including these group sessions, counseling, and medication.

The pharmacy at Cook County distributes thousands of doses of psychiatric medication every day.

ROBINSON: They got me a pill called Buspirone, Zyprexa, and Remeron.

- Mm-hmm.

- So that's three different medications that I take.

When I first began speaking with a psychiatrist, they told me the symptoms I was giving of schizophrenia, they say, was me hearing voices.

- Mm-hmm.

Like, feeling as if I'm always triggered to do something wrong to somebody, and me having to tell myself, "No, that ain't... That ain't how I need to go about it."

- Okay, this medication, is it helping to give you the strength to not listen to the voices?

- Yeah, most definitely.

- Most definitely?

- Yeah.

- Okay.

JOHNSON: The vicious thing about mental illness and medication is, as long as I take the medication, I don't have the symptoms.

Get your I.D.

Sign your name.

NARRATOR: Detainees are not allowed to leave the jail with medication in hand, so on their way out, they're given prescriptions.

WOMAN: As far as the psych medication, do you know you can go to Stroger?

- Oh, I don't, I don't take psych medication.

- You don't?

- No, ma'am.

They just legalized weed.

- (chuckling): Well, just in case, you know it's West Harrison, to the pharmacy on the first floor.

- Okay.

JOHNSON: When I leave here, there is nobody to make me take the medication or no one to check up.

If I'm not taking the medication, the symptoms reappear, then the behaviors that accompany the symptoms also reappear.

WOMAN: What were you charged with?

- Uh, domestic battery.

JOHNSON: And it's a vicious cycle.

It is vicious.

GUARD: Next man who needs a jacket.

- Sometimes you get locked up when it's hot outside, and you get out, and it's the winter.

Thank you.

♪ NARRATOR: In America, the treatment of the mentally ill has always swung between compassion and punishment.

But future approaches may emerge, as new tools provide greater insight into the brain.

RACHEL YEHUDA: What these tools can do is help us move the needle forward in terms of telling us that we're on the right path with our understanding of what the fundamental disease processes are.

♪ NARRATOR: To unravel the roots of mental illness, scientists look to genetics and brain imaging.

And find evidence Dorothea Dix and Thomas Kirkbride may have been right: environment and experience are key.

YEHUDA: Every experience puts some kind of an imprint on us, and then we walk around as a collection of those experiences, and that collection is encoded in a biology.

And what we've come to understand is that environmental events can really change gene expression and contribute to why people feel so utterly transformed by a traumatic experience.

NARRATOR: Genetics do play some role in mental illness, and recent studies suggest experiences can switch key genes on or off, affecting who actually develops disease.

YEHUDA: So you don't even have to worry only about your own trauma history-- the experience of your parents and your ancestors, this whole chain of intergenerational responses contribute to how you approach your current life circumstances.

♪ NARRATOR: After six months behind bars, Jeremiah Robinson has been released for the 15th time.

He's living with his four children and fiancée.

ROBINSON: It's been kind of rough, trying to take care of the kids, you know, trying to find me a source of income, but, um, I've been maintaining, you know, staying focused.

♪ MAN: What's your dream for her?

To...

Put her in a better environment.

That's my dream, man.

Have her grow up with some stability, you know?

Not as many worries and problems that I've had.

(children calling) COOMBS: What would it look like if we lived in a world where fewer people are traumatized, where fewer people have to live in a way that continues to propagate a lot of suffering?

Will we see serious mental illness at the same rates?

Maybe not.

♪ ANNOUNCER: Next, on "Mysteries of Mental Illness."

MAN: The neurosurgeon is going to implant two electrodes in my brain.

MAN: People might say it's a little creepy that we're actually going to manipulate someone's brain, but these are very ill patients.

I'm so desperate at this point.

TIMOTHY LEARY: Turn on, tune in, drop out.

WOMAN: After taking a psychedelic, people didn't want to go to war.

It is a tool that facilitates healing.

MAN: E.C.T.

is by far the most effective treatment in psychiatry.

MAN: You're introducing electricity into the brain.

MAN: For people who have very severe depressions, it's a lifesaver.

WOMAN: It's critically important to give people a choice.

MAN: Surgery, it's a gamble.

This is the final frontier in psychiatry.

It's my best and last hope.

ANNOUNCER: To order "Mysteries of Mental Illness" on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

This series is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

For more about "Mysteries of Mental Illness," visit pbs.org/ mysteriesofmentalillness.

♪

Support for PBS provided by:

Funding for Mysteries of Mental Illness is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Johnson & Johnson, the American Psychiatric Association Foundation, and Draper, and through the support of PBS viewers.