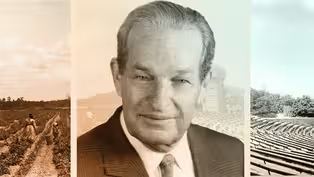

The Playmaker: The Story of Paul Green

7/11/2024 | 1h 19m 12sVideo has Closed Captions

Discover the life and work of Pulitzer Prize-winning NC playwright Paul Green.

This documentary takes a deep dive into the life, creative work and social justice advocacy of the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paul Green. A native son of North Carolina and a champion for racial equality, Green went to Broadway and back with a dream that someday he could write a new ending for the Old South.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

PBS North Carolina Presents is a local public television program presented by PBS NC

The Playmaker: The Story of Paul Green

7/11/2024 | 1h 19m 12sVideo has Closed Captions

This documentary takes a deep dive into the life, creative work and social justice advocacy of the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paul Green. A native son of North Carolina and a champion for racial equality, Green went to Broadway and back with a dream that someday he could write a new ending for the Old South.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch PBS North Carolina Presents

PBS North Carolina Presents is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[piano intro] ANNOUNCER 1: This program was made possible in part by the Paul Green Foundation, celebrating the release of a new essay collection.

Paul Green, North Carolina writers on the legacy of the state's most celebrated playwright from Blair Publishing.

Support also comes from the Stephen King family and from the Stephen Foster Story.

Celebrate American history through music, drama, costumes and dance at the Stephen Foster Story, only in Bardstown, Kentucky.

Additional funding comes from the North Carolina Botanical Garden Foundation, inspiring appreciation and conservation of plants, and advancing a sustainable relationship between people and nature.

Further support comes from these sponsors.

[uptempo bluegrass music] More information about The Playmaker can be found at theplaymakerfilm.com.

[intriguing music] BETSY GREEN MOYER: Paul Eliot Green was a North Carolina playwright, humanist, and lifelong champion of racial equality.

He was faced with a population that went to church on Sunday and went to a lynching on Monday.

- I often say about Paul Green that he's like a chronicler because he was living right there with these people.

- Telling the stories of certain people whose stories are not being told.

- He got early attention on Broadway and won a Pulitzer Prize for his In Abraham's Bosom.

But it was a very, very, very difficult play.

- It's not easy to take racial tensions and put that on stage.

- There's a message to be sent here, and he's sending a message.

MARSHA WARREN: Paul Green used his writing to advocate for people.

- It's interesting how allies are formed, right, and alliances are formed.

- I was fearful that we would get up in the morning and there would be a cross burning on our front yard because my dad's liberal views on civil rights.

PAUL GREEN JR: Redneck legislators in Raleigh considered him to be a bloody red Communist.

I mean, why else would he want to defend the lives of Black people?

- How is this voice-- - He was way ahead of his time.

- Imagine yourself caring-- PAUL GREEN JR: Well, he's an idealist.

Don Quixote, he was an idealist, he and his windmills.

- Some people go to a job and never touch on who they might be, what they might do.

PAUL GREEN JR: I think you'd have to put him down to being a character.

Not everybody agreed with him.

Many people thought he was heroic.

LAURENCE AVERY: He was born in Harnett County on a farm that was right close to the Cape Fear River.

[melancholy bluegrass music] ♪ ♪ MARSHA WARREN: It's a really unique story because he was a farm boy.

He, as a child, as a young man on the farm, was an avid reader.

He'd have one hand on the reins of his plow with a book in his hand.

- He was always learning a language or memorizing poetry, even as a kid.

- That was an age of transformation for North Carolina.

With the end of Reconstruction, conservative southerners retook control of the operations of state and county governments.

They began to re-establish white supremacy, the Jim Crow South.

Slavery was no more.

But there are waves of Klan activity.

[crackling fire] The late 1860s, early 1870s, you see the first emergence of the Klan.

Starts in Tennessee.

Spreads quickly across the south, including North Carolina.

- --you head to North Carolina.

And my name is Roy Will, and I'm not ashamed to be a Klansman.

Amen.

[cheering] - The organizations that were dedicated to white supremacy, they were-- they were terrorists.

- The white man has been the supreme race.

We, the knights of the Ku Klux Klan, intend to keep it the white race.

- That's the kind of thing that Dad grew up observing.

And to me, it's no miracle at all that he either became one of them or he-- he opposed them.

PAUL GREEN JR: He was raised amongst Blacks.

Well, they were his people.

His best friend was this one guy, Rassie.

His mama wanted him to become a Baptist preacher.

Well, why did she want him to become a Baptist preacher?

So that he could change people-- because they can see the injustices, and do something about them.

- He came to school in 1916.

So '16/'17 was his first year.

And if you remember, that's when Woodrow Wilson decided we had to go to the aid of France in the First World War.

[martial orchestral music] There was a patriotic rally at Chapel Hill in the spring of 1917.

Paul got enthusiastic and patriotic and joined the army.

MARSHA WARREN: This was going to be the war to end all, wars and this was going to be his calling.

And he believed that if it really were "the war to end all wars"-- because he was very opposed to war-- then I'm going.

And he enlisted.

LAURENCE AVERY: He was an engineer.

He was building trenches and laying landmines and stringing up wires for communication.

There were, of course, squadrons of Black soldiers.

They weren't integrated.

But Paul couldn't help noticing that in France, the Black soldiers were treated just like they were white soldiers.

That was the first experience he'd had of seeing Black people with the freedom and the standing and the respect that white people normally had back at home.

And so it really registered with him.

[mandolin music] [cheering] - After two years of the trenches in France and Belgium, he came back to school, and now it's 1919.

- While Green was in France, Professor Fred Koch arrived in Chapel Hill, and he was quite a character-- [uptempo '20s jazz] --a dynamo, a publicity machine, I think.

Just within a year or two, he had organized a theater group that became The Playmakers.

He said, we want to write folk plays, plays about the experience of the people around us in our communities and on our farms.

And so Paul got interested in the theater.

And one of his English professors said Paul should write a play and enter it in a contest that Koch had going.

LAURENCE AVERY: He based the play on an actual historical event.

At the end of the Civil War, the captain of the Yankee forces and the daughter of the president of the university fell in love.

And so Paul called his play Surrender to the Enemy.

MARSHA WARREN: And so when he returned in 1919 and was able to be in the playwriting course with Prof. Koch, there was Elizabeth Lay.

LAURENCE AVERY: She came from a very refined family.

She was extremely talented, and she was sophisticated, and she had elegant manners.

- And then came along this country boy Paul Green.

And of course, she fell for him like a ton of bricks.

PAUL GREEN: She was interested in drama, and I was interested in drama here with students.

And we used to work together.

We'd paint scenery what time we weren't courting.

And the courting business got in the way of the painting.

LAURENCE AVERY: The Playmakers organization had become so elaborate, it toured all over the state.

And there were organizational problems.

I mean, how do we get costumes there?

And where are people going to eat when they go to Timbuktu?

And Elizabeth was very methodical, very capable.

And so she handled all the business of The Playmakers by that time.

Carolina Playmakers became an internationally known theater group and very influential.

PAUL GREEN: Well, the early days of the Carolina Playmakers, nobody knew-- knew anything about plays in North Carolina.

So it was an exciting time.

And we had great ideas.

We thought we were doing tremendous things for the American theater, and we were doing a little something and doing most for ourselves.

We had great fun.

I got a wife out of the movement, so I ought to be happy.

♪ ♪ [projector whirring] When I was a little boy, about 10 years old, I was with my father in Angier, North Carolina, and I stopped by the little old station to watch the locomotive come in.

They came on in, and there was an old wood burner.

And as it struggled up in and stopped, it coughed and so on.

And the engineer got down under that, began to squirt oil on its rusty joints.

And a great Negro teacher came strolling up.

He got off the train, and he walked up.

And he had on a wonderful white shirt.

And he has taken his children to an excursion in Durham.

And he asked the engineer, who was down under the old rusty locomotive, Captain, what time do we get to Durham?

And well, this greasy white man under the-- down underneath and the Negro up above, something infuriated the white man.

And he said from underneath the old locomotive, it's none of your damn business.

And the Negro backed back and said, well, Captain, I didn't mean any harm.

And I stand there, a little boy watching him.

Well, somehow it infuriated him.

The white man came out from under the locomotive, and there was a Confederate soldier standing there, leaning on a heavy cudgel stick.

And he reached around this engineer, grabbed this cudgel, and hit this Negro teacher across the face and split his face wide open.

And the blood flew.

And all that this Negro teacher said was, hey, Captain, you done ruined my shirt.

And he put his handkerchief to his face and he staggered back into the train.

And the old engineer said, all aboard, and crawled up and pulled the cord.

And away it went to Durham.

Well, I thought about this terrible injustice.

And later, when I began to write plays, I thought, well, I'd love to write one about a Negro schoolteacher.

Now, that turned out to be a And all I could do was to write a little play to help maybe bring some light into the world that turned dark when that man hit this other man with this terrible stick.

Captain, you done ruined my shirt.

[train chugging] - He got early attention on Broadway and won a Pulitzer Prize for his In Abraham's Bosom in 1927, which really put him on the national stage.

["bosom of abraham"] ♪ Yessir, rock my soul in the bosom of Abraham.

♪ ♪ You rock my soul in the bosom of-- ♪ - I didn't know what New York meant.

I didn't know what Abraham's Bosom meant.

♪ Lord, you rock my soul.

♪ ♪ Why don't you rock my soul?

♪ ♪ Well, you rock my soul-- ♪ - Well, all of a sudden, he was famous.

♪ You rock my soul in the bosom of Abraham.

♪ ♪ You rock my soul.

♪ PAUL GREEN: Winning the Pulitzer Prize or getting some plays on in New York didn't change my life.

And maybe it should have gone to Maxwell Anderson for one of his plays.

- His modesty was everything.

And he said he only won the Pulitzer Prize because Eugene O'Neill and Maxwell Anderson hadn't written a play that year.

[chuckles] That's the kind of person he was.

BETSY GREEN MOYER: He was proud of the play because it tells the struggle of a Black man who aspires to become a teacher and meets problems along the way.

♪ --bosom of Abraham.

♪ ♪ You rock my soul in the bosom of Abraham.

♪ ♪ You rock my soul ♪ in the-- - It was such a harsh play.

It's a very, very difficult play.

In Abraham's Bosom was able to give flesh and blood characters.

Putting those on the stage-- it was not a shuffling servant.

BETSY GREEN MOYER: Of course, the play catapulted him into fame.

However, I'm sure you're aware of the controversy that surrounded it.

This was the first play ever to win a Pulitzer Prize about the Black man.

It's not only about a Black man, but the downfall of a Black man.

♪ Lord, you rock my soul.

♪ BETSY GREEN MOYER: White people in the story are not given a very good image, and there was great controversy about it.

People who said that he-- he didn't deserve the prize, no prize has been ever been-- blah, blah, blah, blah, you know, the usual.

- (SINGING) You rock my-- why don't you rock my soul?

[applause] - The difference between theater then and now in the 1920s and such, the stories that were being told were mainly white stories for white audiences.

Of course, everything was segregated back then also.

Any Black theater or Black stories were being told within the confines of, you know, the Black community.

[light piano music] JOHNNY JONES: Blacks were just starting to get opportunities on Broadway and things like that.

It's between the '20 and '40s.

So there was kind of, like, budding interest of different characters and different stories starting to develop.

It's kind of a no-man's land.

It was sort of an unknown.

[light piano music] - Any Black stories that were being told were at the expense or humiliation of Black people at the time.

ACTOR: Mr. Tambo, how do you feel this evening?

WHIT WHITAKER: You know, you had minstrel shows or, you know, whites dressing up in blackface.

It was used as a as a power structure of sorts from Jim Crow to jazz.

ACTOR: What's the trouble, Mr. Tambo?

- I appreciate Paul Green humanizing Black people at the time.

He was probably trying to endear himself to white people, you know, feed it to them like medicine, get them used to it.

But I also think if you were really genuinely wanting to tell, you know, African-American stories, the stories of the people, you would have just allowed them to tell their story.

And if they weren't able to tell them in a white theater or white venue, so be it.

I think it's important that he did try to get the stories out.

I can't speak on how honest or earnest he was or his motivation for doing it.

♪ ♪ - Man, a human being is faced with the burden of his own sense of duty, sense of what he has to do.

And if he's a fool-- I've been foolish enough on plenty of things-- but if he's deep down a fool, he'll mistake some good happening as a kind of an ultimate recognition of something accomplished, and his job is done.

But no, all those things are only encouragement to persist in your endeavor if it's good.

And I thought mine was good, and I was trying to write about the people that I knew, trying to put their dreams forth, say words that they would like to say maybe, and talk about where are we going in this world.

- Dad was inspired by the folk.

He grew up with the folk.

The people whom he admired and he identified were just ordinary, ordinary people.

Wherever there was a person, he thought he had a story.

PAUL GREEN: Since I was a boy, I've been interested in what people say and what they believe.

And I think in a way that the playwright has a duty of trying his best to say things that are true about human beings.

[uptempo bluegrass music] [laughter] - My mother and he, they spent many hours traveling all over North Carolina.

They heard of somebody who had a story to tell, they'd pop in the car and go down and hear it.

- At 15 years old, I started taking notes, and meeting people, and listening to what they say, and then go home and write it down.

If they told a story, "write down the story."

I can use the new phrase.

- He'd run into a game or a song or a joke, and he would write it out on these cards.

And we've got those cards now.

There are thousands of them.

- This man knows about people.

He cares about people.

He's gone inside and listened and felt and watched and got into the gristle of folk.

- This is one of many volumes of folklore notes with incidents, expressions of all sorts of things.

And some of them I've used in plays and some in stories.

LAURENCE AVERY: Paul's plays in the 1920s especially, were the first depictions of the actual experience of Black people by anybody who knew what those experiences were.

- He got into a feeling of people, who these people are, what they do, why they do, where they're from, what their need is.

- The popular literature of a generation or two before Green was the kind of romanticized Old South.

And he celebrated the culture in many of his works, but he also recognized the-- the sins, the-- the harsh truths in other works.

He was pretty brave with his topics, in particular In Abraham's Bosom and The House of Connelly.

Both plays, he deals with miscegenation, and this is on stage.

These people are going and they're going to hear stories about white brothers and Black brothers and their conflict with each other, with their father.

- This, of course, dates back to the pre-Civil War slave era, when some slave owners raped female slaves.

They produced offspring where the child was a slave, but whose father was actually not.

[intriguing music] - Writers were dealing with the harsher truths about the Old South.

What made it not so great after all, that all these codes of honor and morality and loyalty and-- they were empty codes.

These women were raped by their owners, and children were produced who were not recognized by their fathers.

BARBARA MONTGOMERY: He found the inside, the workings, the feelings, the frustrations, and the equality of these other people-- my people.

BYRD GREEN CORNWELL: Seeing is believing.

And he saw intolerance at work, observing how differently the Blacks were treated from the whites-- undeservedly different.

MARSHA WARREN: He's like a chronicler.

He's like a reporter.

He's telling these stories because he was living right there with these people.

He was recording all of those things that were happening to people.

- I think he viewed life as a drama.

That's the way he interpreted life, and that's the way he wrote about it.

PAUL GREEN: I wrote Negro plays.

I wrote articles.

It was no great accomplishment on my part because that's just the way I was.

I felt it was just nonsense.

- This was a story that had to be told, and he was going to tell it.

[inspiring music] ♪ ♪ He found his path, his goal, and he went after it.

- He was striving to say something.

That's why he wrote.

And there were some of the leaders of Chapel Hill.

He was just way ahead of them.

PAUL GREEN: Professor Williams came to me once or twice and admonished me about my attitude.

[uptempo '20s jazz] - Dad was preaching racial equality and all that long before it became the word of the day.

He was felt to be kind of a firebrand.

[cheers and applause] [insects chirping] [wistful piano] - This South of ours is a land of violence.

And violence is somehow means a great clashing of wills, oppositions of endeavors, and fervors and mutilations in certain places.

And we always had the Negro.

So the raw material was here in the South.

Theater is part fiction.

You'll never find in life a plot.

You find the raw material in the characters' incidents.

Then you have to arrange them.

[wistful music] ♪ - The Group Theater grew out of the Theater Guild, which was one of the big producing organizations in the professional theater.

They said, let us do The House of Connelly.

- The Group Theater took the play for a summer and went up to Connecticut, I think it was, and practiced.

And they worked out how they were going to do the play.

Paul Green observed.

He kind of found it amusing, from what I can tell.

It was this method acting.

He thought some of their exercises were silly.

- The Group Theater wanted to use the theater to improve society.

Some of them were communists.

All of them were socially conscious.

And it turned out they didn't like the way the play ended.

Two of the Black women who worked for the family of this rich landlord resented their mistress, you might say.

And so the play ended with them choking her to death.

But that didn't seem to improve society very much, so they persuaded Green to give it a happy ending where she doesn't get choked to death.

- I was so surprised by it, when I first discovered the play, that there were these two endings, that he had changed the ending.

But then the changed ending doesn't change what the play says, because in either case, the play is saying the South has to change or it will die out, this particular culture will die out.

And in one version, they reject change, kill the agent of change.

And with her, goes the next generation of the House of Connelly.

And then in the play where she lives, you assume there will be another generation, and it will be different because she's different.

[applause] ♪ [chuckles] When I auditioned for House of Connelly, it was the first Paul Green play I had ever done, and was just totally enamored of it.

I loved it.

When I first read it, I thought, my goodness, this is-- this is-- this is great.

This is-- finally get to do something of the Old South, you know?

[chatter] It's not easy to take the racial tensions, you know, and put that on stage.

One of the women to play a big sis, she couldn't do it.

An African-American woman, she just said, I can't-- I just can't do this.

I can't.

And it got quite-- it got quite a bit of, you know-- there was a lot of hoopla about what was going on, and the language that was used.

And for an audience of this particular 21st century to hear the n-word used quite often.

- No, this is their home, Patsy!

Their home!

And I'm not running from it!

- I was watching from backstage, and you could see people doing-- moving in their seats.

It stirred up what theater is supposed to do.

It's supposed to stir you up.

It's supposed to get you excited.

That's part of history, of-- of the supreme, bigoted human being.

But that's part of history.

The treatment of other human beings, it's been there.

Look.

So people should be reminded, I think, of those things-- where you come from.

Yeah, it's important that it should be done.

And it should be done more than it is.

And it should be done at the pinnacle, the mecca of theater-- Broadway.

[applause] [projector whirring] - Yeah, there were a lot of people in Chapel Hill that thought he was off the rails.

And in the run up to World War II, and after World War II, in the McCarthy era, people equated propensity to defend the Black man and try to make things better for him with socialism, if not worse-- communism.

- There was a leftist perspective in his work that, I think, at the same time, spoke to African-Americans, and particularly, African-American radicals.

- And so he had his share of-- of redneck legislators in Raleigh and others who considered him to be a bloody red communist.

Then why else would he want to defend the lives of Black people?

Why else would he want to celebrate their culture, their civilization, their music?

It was clear to all of us young Greens that we had a very notable father.

We were very nervous around school at being singled out, either positively or negatively.

- I was always fearful that we would get up in the morning and there would be a cross burning on our front yard because my dad's liberal views on civil rights.

- He was in the country where there were lynchings every once in a while.

We never talked about it.

He never wanted to talk about that stuff.

But when he got mad, I can just remember, he came home one day just absolutely apoplectic.

And he went into a funk for many days.

And the next thing I knew, he was furiously at work at the typewriter.

And in no time-- at least my recollection-- he'd cranked out this electrifying, just devastating one-act play about the cruelty of the North Carolina Chain Gang.

- Jim Crow's segregation extended into the criminal justice system at every level.

African-Americans, of course, could not vote, so their voice was not heard in the selection of county officials.

In most court systems in the South, African-American defendants did not have the same rights as whites did.

And this included things like not being able to testify against whites in a court of law.

You're only hearing one side of the story.

The harshest punishments were reserved for African-American defendants who were much more likely to get the death penalty.

- They read in the paper about two North Carolina convicts who-- who were in a chain gang and had been left out in the cold, and their feet had frozen and had to be amputated.

[melancholy bluegrass] BETSY GREEN MOYER: The newspapers were full of this kind of report.

I mean, horrible, horrible things like that.

My dad was incensed by this.

He went around and collected money to hire a lawyer.

- So he complained about it up the line, basically explaining to the governor that if something wasn't done, he would take his national reputation and he would talk about it beyond North Carolina.

- The story is told that he went home and wrote this play, The Hymn to the Rising Sun, in one afternoon, just bang, bang, bang.

You can hear that old Underwood typewriter clacking away.

- He still told the story beyond North Carolina in his work.

He just put it into literature so we could pretend it was fiction.

[melancholy bluegrass] ♪ PAUL GREEN: Yeah, the Chicago Federal Negro Theater production Hymn to the Rising Sun banned-- - Paul Green came to me at a very good time in my life, doing many plays, the Negro Ensemble Company at La MaMa, Joseph Papp.

I had done Broadway, I think.

I had toured a lot with Cafe La MaMa.

A friend of mine introduced me to an anthology of Paul Green's plays.

And I read these plays and felt Paul Green.

I felt him.

And he-- Well, I felt him because he spoke to me through his words.

And how he spoke to me got to me inwardly, how he formed-- how he forms his words and how he says-- and then when he-- what he gives the characters to say to each other about each other.

Hymn to the Rising Sun was a great experience for me in that I had all these actors that were in the stockade.

In rehearsal, I spoke with each one as to what their crime was and also how they individually felt, Black and white, about being in this stockade with the other.

[melancholy bluegrass] I had the audience come in, and rather than to go right to their seats, and the set was here, I had them go along that side wall and come in through the back of the set, closed-in space with bunks and chains.

The ugliness, sadness, and the fear that permeates the-- a place like that.

Later on, as they would view the play, they'd have another feeling.

They'd have a sense of having been there a little bit.

- Well, these two have been put together.

This is a much older picture than this one.

But this is Dad standing in front of one of his cabins, a building on the property that he could use as a study.

He did not ever write in the home with the family, even very early on.

PAUL GREEN JR: He wanted to get away from four screaming kids, and visitors, and so forth, and he would hole up there and write.

- You wouldn't bother Dad.

I mean, we weren't afraid of him, but we respected him.

[projector whirring] - Well, he was a man of very wide range of moods.

When he was happy, he-- the placed just burst with his big personality.

But he was often very sad.

[bluegrass music] The awful things that were going on in the world in the '30s, '40s and '50s just saddened him.

He'd read the papers and get down in the dumps about some things that he read.

- I think he was a guilt-ridden person.

He was sensitive, very sensitive to other people's pain.

He saw what he hadn't accomplished as much as what he had-- more so.

Of course, when we were kids, we always thought we'd done something bad.

And mother would say, oh, don't worry, Byrdie, he's just gathering goat feathers, which was the way she put when he was pondering over his next-- what he was writing.

- He was a perfectionist.

And we just were in awe of him, but he was not in awe of himself, I'll tell you that.

PAUL GREEN: I've never written a play yet that I've been satisfied with.

I do the best I can, but my talent is limited.

And I keep maybe consoling myself by saying, well, like in the Bible, this man, this master went away and he gave one two talents and another one 10 talents.

And when he come back, the two-talent man, if he's done as well as he can, he gets the same reward.

- Paul Green, we know him so much as a playwright, but he was very interested, as I've already said, the chain gang and other-- the problems with people not having representation when they needed it.

He was also totally opposed to the death penalty.

LAURENCE AVERY: In the early 1930s, a murder case came up that was a good bit like the murder in In Abraham's Bosom.

A sharecropper, a tenant farmer kills the landlord.

That same situation happened in real life.

Green found out about the case, and his sense was that the Black man was not getting a fair trial.

The jury was biased against him, and it was all white.

And so Green helped hire a better lawyer.

Nevertheless, wound up with the Black man being convicted, and within a few months, electrocuted.

He became an ardent opponent of capital punishment.

PAUL GREEN JR: His way of demonstrating about something was to expend some of his standing in the state by quietly ridiculing what it was doing, or quietly weeping over it.

When there was an execution going on in Raleigh, he would go to the prison and stand outside.

- He would stay there until-- I don't know what signals that a person has died.

Maybe a bell rings.

[bell pealing] And one person, at least, was out there protesting.

BYRD GREEN CORNWELL: A one man-opposition or expression of defiance for this injustice that was being committed.

MARSHA WARREN: As the years went by, more and more people would join him.

Now hundreds of people are out there.

PAUL GREEN JR: And I think he'd be pleased to see how almost never do you read about an execution in North Carolina anymore.

And when I was a kid, they were frequent.

- My skin makes me the enemy, so that's why I know the death penalty was designed in mind to be the end of me.

Most of us wanted to see college, but America gives us the penitentiary.

And that's been the American way of life since the turn of the 20th century.

- He did push the pendulum a little bit towards a more liberal stance on that issue.

But that pendulum has a way of swinging back.

- No justice!

CROWD: No peace!

- We're fired up!

CROWD: We're fired up!

- We're fired up!

CROWD: We're fired up!

- Won't take it no more!

CROWD: Won't take it no more!

- Won't take it no more!

CROWD: Won't take it no more!

PROTESTER: Won't take it no more.

- I think people probably didn't like to see Paul Green coming to their front door, because they knew that he wanted to get money for some cause.

If it wasn't to hire a lawyer to defend someone on death row, it was to gather money to start the North Carolina School of the Arts.

Any good cause, he was right out there.

His wallet was talking as well as his writing.

[chuckles] - I needed money awfully bad.

I was getting $2,500 a year here at the university as assistant professor.

And I had a growing family.

[chuckles] And I had two suits of clothes, and the seats of the breeches were thin.

I couldn't even-- I had to face the class all the time and write backwards on the blackboard.

So when I got this offer from Hollywood to pay me enough in two or three weeks more than I could-- or a week, two weeks, more than I could make in a year, I got a leave of absence.

But at the same time, that was the great love of the motion picture medium.

It's one of the great mediums of artistic expression in the world.

It's a universal medium.

[captivating music] I went out there with great hopes.

[camera shutter] - When film came out, he was very excited about it.

He saw movies as a chance to bring the stage to everyone.

- My dad saw a golden future.

All these wonderful things would be possible to share.

ANNOUNCER 2: We'll see, for the first time, the beautiful panorama of the fabulous city of Hollywood.

LAURENCE AVERY: Green got a contract to write for the motion pictures.

The first movie he wrote was called Cabin in the Cotton.

It attracted his attention because it was about a sharecropper's family.

It was a social situation that he could relate to.

Green went to Hollywood with high aspirations.

But then, in the movie business, it wasn't the writer, it was the producer who would-- who would cut things, and leave things out, and change things.

MARGARET BAUER: Whatever he did, it was too literary.

And they would chop it all up and make some vacuous movie.

LAURENCE AVERY: Green very quickly got extremely frustrated with Hollywood.

But he was making so much money, that he-- he would go to Hollywood for two or three weeks or a month or so and make thousands of dollars, and then spend the rest of the year doing what he wanted to do.

- I think one of Green's problems with movies was he thought any audience could handle these tough truths and these tough stories, and that we were short-changing movie audiences by wanting to give them just vacuous entertainment instead of thoughtful stories like the kinds he had written for the stage, and ruining this opportunity to reach the masses with drama-- real drama.

He redirected his attention to communities having theater, and ultimately to outdoor drama, that would gather people in a particular area to find out about that particular place.

And I mean, first he was called on to help start the Lost Colony.

NARRATOR: There is a narrow strip of land that juts out to sea near Fort Raleigh, runs down to the cape, which the Indians named Hatteras.

And we may wonder what the first colonists thought of this desolate and beautiful beach.

- The Lost Colony, and the story surrounding it, is one of the most fascinating and discussed aspects of North Carolina history, even though we don't know a lot about it.

In the 1580s, the English made their first real attempt to establish a settlement in North America.

And today, the initial settlement is on Roanoke Island, part of the Outer Banks.

We don't know what happened to those 112, 113-- something like that-- settlers who were left on Roanoke Island.

And they become known as the Lost Colony.

Initially, the-- the whole mystery wasn't an enormous deal until much later.

People became increasingly interested in what happened.

There's this idea of developing an outdoor pageant, an outdoor drama to tell the-- a romantic, mysterious story of the Lost Colony.

[uptempo jazz] ♪ PAUL GREEN: Well, we started in 1936 with the WPA.

It was the time of a depression.

And we had one mule and a scoop and about 100 CC Camp boys digging and hauling sand here with the connivance, really, of Uncle Sam and the local citizens.

We were, able, finally to build this.

It's important to build the amphitheater where they'd be produced in the environment where the characters live.

And so the audience feel that these living beings walking on this stage are brought to life in the actual setting of those people who, as I say, perished here.

[bell ringing] - Paul Green is the creator of the outdoor symphonic drama.

This is a genre that began right here in North Carolina, and he was the first.

- He incorporated dance, music, words-- everything.

PAUL GREEN: Song, old hymns, folk tunes, music, music.

Well, I usually call these plays symphonic dramas because the music and the spectacle, the dance all interwoven, it sounds like a symphony.

[inspiring bluegrass music] ♪ - It was first produced in 1937, and it was attended by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, actually.

And it's been playing ever since.

- He knew that this was the medium that he was meant to do.

And he loved history.

And he wanted to bring theater to the people.

- The life I knew was the people-- the folk.

I grew up in Eastern North Carolina, and that's the-- so I wrote about the folks I knew.

I felt that there was a great storehouse of dramatic material in the history, the legends, the myths, and so on, of our people.

- He went on, then, to write 16 more outdoor dramas across the country, going to the very place where this particular history had taken place.

PAUL GREEN: That's been a sort of philosophy all the way through, to try to build these amphitheaters in different parts of the country where great events represent real struggle on the part of the people involved.

WHIT WHITAKER: It's a genre that can bring people together from different walks of life.

It can make you feel good as far as making you feel historically proud.

- This play in this amphitheater, night after night, the people come here, and I think they get renewed.

- The people of America were out in the theaters.

They didn't have to be dressed up like you have to be when you go to Broadway.

You didn't have to have fancy clothes.

You could come and see theater.

And he was very pleased about that.

- I'm looking forward to seeing it twice.

And there are not many shows of mine that I can sit through even once.

[chuckling] And that's the truth.

BETSY GREEN MOYER: The Lost Colony was still being played every summer.

In fact, there are four of his plays that are being produced every summer-- The Stephen Foster Story in Kentucky, Trumpet in the Land in Ohio, The Lost Colony, as I mentioned, in North Carolina, and Texas in Texas.

- You can't afford, from the point of view of the artist, not to make your work come first, to put something on the stage so that people will feel it in here.

And we're going to do all we can to help.

But it's up to you.

And God bless you.

If there isn't a god, if he isn't one, well, bless you anyhow.

Thank you.

[applause] [projector whirring] - All right, this is Paul Green and Richard Wright, I'm pretty sure.

And there was hell to pay because Paul Green had brought an African-American to Chapel Hill.

They were collaborating on the dramatization of Wright's book Native Son.

- Richard Wright had written a novel called Native Son, and it was really quite harsh, very, very harsh.

Richard Wright wanted to have it dramatized for the stage, for the Broadway stage.

- Green was shocked when he read the novel and thought it was too, too violent to be of interest to him.

PAUL GREEN: It offended me, yeah.

But I guess I had a real feeling for Wright.

MARGARET BAUER: They met on terms, and then Green brought Richard Wright to Chapel Hill.

And I think he really wanted to help because he wanted to desegregate the campus, if only for a couple of weeks or a summer.

♪ - And they found a room at the University of North Carolina to work together.

This was a very unusual thing, a Black and white man working together.

- It was the two of them, and they worked on it on a segregated campus.

- He was here about two weeks, I think.

And they worked every day, talking about the script and working out elements.

How would we do this and how would we do that?

- The last days, they're wrapping things up.

The chancellor, I believe it was, called the office and said, aren't you finished yet?

There's a mob growing at a drugstore nearby, and they're planning to lynch Richard Wright on the UNC campus.

MARSHA WARREN: Paul Green was very worried about him.

And so he followed Richard Wright over to his rooming house and hid in the bushes with his baseball bat.

[car horn] MARGARET BAUER: So they collaborated in Chapel Hill, and everything went OK. And then they went up to New York and joined with Orson Welles and Houseman for the actual play.

And that's when things got interesting.

[intriguing music] - They had worked pretty amicably together, but Welles and Houseman had different ideas for the ending.

Probably, it looks like more in line with what Wright had wanted to do and Paul Green had changed.

- I was listening to these interviews.

Twice or three times I heard Green comment, he called me Mr Green.

I called him Dick.

Why didn't I say, call me Paul?

I thought, this really bothered him.

He knew that there were limits to, apparently, his own liberalism.

So I don't know what the story is, but whatever it was, it really bothered Green, that he had not treated Wright as an equal.

[melancholy bluegrass music] REPORTER: You grew up in Eastern North Carolina at a time when most Blacks were hardly better off politically, economically, legally than they had been under slavery.

How did you happen to develop your concern for-- for the conditions of Blacks?

PAUL GREEN: And there was a Negro family living in that shack.

And they had a little boy, and this little boy was Black as the ace of spades and he was same age as I was.

And I met up with him when we were four years old.

And so Rassie and I became very good playmates.

And I learned that, maybe with some embarrassment, that he had more sense than I had.

He knew much more woods lore.

He knew how to spit between his teeth.

He knew how to put dogwood berries up his nose and blow them out like a pop gun.

I can still see his face.

He had a way of wrinkling his nose when he laughed.

Well, to make a long story short, he and I grew up, and at 10 years old, he got typhoid fever and he died.

My father and I built a coffin for him.

And we were talking about it on the way back.

And I got some cotton and put it in the-- for his head to rest on.

And we took him up in the field and buried him.

[SLOW AND STATELY BLUEGRASS MUSIC] - There is so much to idolize about Paul Green, but he was also very human.

And that's the Paul Green that I liked.

You know, I-- if you have an idol, you can't strive to be like that person.

You just kind of put them up on a pedestal and say, nice we have this sometimes.

But if you have someone who's worked really hard, and done some amazing things, and made some mistakes along the way, then it gives you hope that, you know, maybe you can do something too.

[projector whirring] [intriguing guitar music] ♪ - In North Carolina.

Paul Green is pretty well known.

But because of what he did ultimately with his writing, he's not as known nationally or internationally as some other writers that were writing at the same time.

BETSY GREEN MOYER: Why isn't Paul Green remembered?

The things that my dad wrote before 1940, they're uncomfortable.

It's-- he's talking about uncomfortable truths that were existent in-- in that time and during his life.

- Now theater is supposed to challenge.

It's supposed to remind you of where we came from.

- If they walk out yelling and screaming, maybe they didn't get the whole idea of what was happening.

- In America, we live in this sort of this space where race is prevalent, where difference is prevalent.

We are on an ongoing journey of defining what America really, really is.

From Richard Wright to Paul Green, different artists show the full landscape of what our nation represents.

We're still basically on that journey.

[music intensifies] - He was writing at a time when these ideas of equality and all were swept under the carpet everywhere.

And all he was trying to do was get them out where people could see them.

He never stopped stating his point and fighting for it.

I really respect that.

[music intensifies] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [captivating music] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [captivating bluegrass music] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: This program was made possible in part by the Paul Green Foundation, celebrating the release of a new essay collection-- Paul Green-- North Carolina Writers on the Legacy of the State's Most Celebrated Playwright, from Blair Publishing.

Support also comes from the Stephen King family and from The Stephen Foster Story.

Celebrate American history through music, drama, costumes, and dance at The Stephen Foster Story, only in Bardstown, Kentucky.

Additional funding comes from the North Carolina Botanical Garden Foundation, inspiring appreciation and conservation of plants, and advancing a sustainable relationship between people and nature.

Further support comes from these sponsors.

♪ More information about The Playmaker can be found at theplaymakerfilm.com.

Preview | The Playmaker: The Story of Paul Green

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 7/11/2024 | 30s | Discover the life and work of Pulitzer Prize-winning NC playwright Paul Green. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

PBS North Carolina Presents is a local public television program presented by PBS NC