The Jewish Journey: America

Episode 1 | 55m 8sVideo has Closed Captions

Trace Jewish immigration to the US over centuries with personal stories and scholars.

Trace Jewish immigration to the US through the centuries. Interviews with top scholars in Jewish history, notable Jewish-American writers, and many immigrants themselves detail the varied stories of migration through the last five centuries, with a rarely explored look at the actual journeys to get here.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

The Jewish Journey: America

Episode 1 | 55m 8sVideo has Closed Captions

Trace Jewish immigration to the US through the centuries. Interviews with top scholars in Jewish history, notable Jewish-American writers, and many immigrants themselves detail the varied stories of migration through the last five centuries, with a rarely explored look at the actual journeys to get here.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The Jewish Journey: America

The Jewish Journey: America is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[Choir vocalizing "America the Beautiful"] ♪ Choir: ♪ America, America ♪ ♪ God shed His grace on thee ♪ ♪ And crown thy good ♪ ♪ With brotherhood ♪ ♪ From sea to shining sea ♪ Narrator: The story of Jewish migration to America begins some 400 years ago in the 1650s, when small groups of Jews arrived, settling in what would become New York and Newport, Rhode Island.

More Jews would trickle in over the decades to such places as Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina.

They played roles in many parts of America's development.

Some even fought in the American Revolution and the Civil War.

In the mid-1800s, a larger migration of Jews arrived from German-speaking lands of Europe.

Some 50,000 came during this period, settling in the Northeast and Midwest.

Jews also went to California for the gold rush.

Famous families, such as the Strausses of Levi Strauss, the Ochses and Sulzbergers of the "New York Times," and the Guggenheims, had their origins in this wave of Jewish immigration to the United States.

As the 19th century went on, more and more Jews came to America, but even as late as the 1870s, their numbers were moderate at just more than 200,000.

That would dramatically change, as millions of Jews would soon call America home.

Man: By the 19th century, the vast majority of Jews in the world were in what we call Eastern Europe and Russia.

They are able to establish communities that exist for long periods of time, for centuries upon centuries.

The idea of living in the same place where your father lived, where your grandmother lived, where your great-grandmother was living, in the same village, the same town, the same city is truly anomalous.

Narrator: Eastern Europe and Russia were the lands that gave birth to the language, literature, and culture of Yiddish.

They were lands of peddlers, tailors, and craftsmen... of religious and political expression... of the Jewish schools known as heders, taught by melammeds.

They were lands of intellectuals, artists, writers, and revolutionaries, where Jews lived in villages, small towns known as shtetls, and big cities.

Few Jews were wealthy.

Most were just getting by.

And some, of course, were very poor.

Anti-Semitism was always there.

But despite it all, the Jews here considered this home.

Man: My father, he was one of 13.

Only seven survived.

And the other kids went to heder, and they had the usual story about the heder and the melammed with the leather belt.

Well, my father didn't go to the heder.

He went to the gymnasium.

He was from a town called Ushitsa.

And the Jews were estate managers for Polish landlords.

See, the landlords owned it.

And so he was caught between the Poles and the peasants.

And it was difficult, but he was not the usual shtetl Jew.

Greenfield: My grandmother was supposed to have been the best cook in town.

Every holiday, even the matzos that we ate were all baked in our house by my grandmother.

It was fresh everything for breakfast, the cake and--ha!

It was a life like you couldn't believe.

Man: I romanticize it to some degree as well.

But when my mother talks about it, she talks about some of the hard parts, too.

My grandfather was so poor, he sent her to work because it was one less mouth to feed.

They had seven, eight kids, and she went to work at 14 in Warsaw.

To be 14 years old and start working-- there's garment factories, which is what my mother did.

Narrator: The events which would bring about the mass immigration to America from Eastern Europe and Russia began in the late 1700s, when the Russian Empire expanded westward, bringing huge numbers of Eastern European Jews into its domain.

Woman: Czarist Russia wants to expand into an empire, so it keeps on annexing more land, but it annexes land with people who aren't Russian Orthodox.

Jews are not seen as part of Russia, because they're not Russian Orthodox.

You don't get to choose.

You are born and registered in a religious community.

You are born as a Jew.

You are born as a Russian Orthodox.

Narrator: The decision by the Russian czars was to confine nearly 3/4 of the Jews of these new Russian territories, approximately a million people, to a specific area known as the Pale of Settlement.

Stanislawski: What they could have said was, "Get out of here.

We don't want you."

One of the czarinas said, "Jews are not permitted in the lands of Christ."

That could've been an option.

Instead of that option, they said, "Look, we're going to magnanimously"-- they used that phrase-- "allow you to remain in this territory where you've always lived."

The population of Jews in Eastern Europe multiplied from around 1 million in 1800 to 6 million in 1900.

That's a six-fold increase.

That's an enormous increase.

How are you going to feed that population?

How are you going to house that population?

How are you going to find work for that population?

So over the next century, as the vast majority of Jews are still living in this territory, there is simply no way that they can survive.

There's no--not because anybody's cutting their throats.

There is this huge economic and social crisis that needs a solution.

People start leaving, start migrating.

A lot of non-Jews are migrating for the same reason.

Woman: The Jewish migration to the United States is, on some level, a kind of continuous story.

So the migration begins small in Bavaria, and then it moves to encompass Jews in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Galicia.

By the 1870s, it starts into the czarist empire, first in Lithuania, and then ultimately encompasses Ukraine and southeastern Russian Empire.

What's important is that, as it moves east, the snowballing confronts larger and larger Jewish communities.

So the Jews of Germany are a tiny community.

But by the time it gets to Galicia, Lithuania, Ukraine, you're talking about millions and millions of people.

Narrator: For some Jews, the choice to leave Eastern Europe and Russia was to escape persecution and pogroms.

For the overwhelming majority, however, the decision to leave came down to economic opportunity.

Stanislawski: They're leaving, overwhelmingly, because of economic circumstances.

The idea that Jews came to America to flee pogroms, for example, is a--is a kind of catchphrase, a cliché, of American Jewish history.

This literary mythology of a Cossack on a horse with a whip beating Jews and then the Jew flees to America is a literary construction.

Narrator: While the attraction to America was strong, many religious Jews saw things differently.

Here were the parents telling their children, "Don't go to America.

"You'll stop being Jewish.

"You'll give up your traditions.

"You'll throw your tefillin away, "your prayer shawls away.

"You'll stop keeping kosher.

You'll stop keeping the Sabbath."

Diner: To put it very bluntly, America was an impure land.

It was impossible to remain religious in America.

They talked about how in America, even the air is full of pork.

There was this attitude in America, "You can do whatever you want.

You're free.

"You don't have to follow rules.

This is the Wild West."

[laughs] "You can be an outlaw."

And it was intoxicating.

So it wasn't freedom of religion; it was freedom from religion.

And people were afraid of that.

Narrator: While many religious Jews chose to stay behind, others were too poor to afford the journey.

Diner: It's an interesting historical irony that the most successful Jews never came.

They had no reason to come to America because they were doing OK.

But it was the poor ones, although never the poorest, they were the ones who went to America.

Man: There was a mental shift in people's way of thinking.

"Why do we have to accept life as it's given to us?

"Why do we have to just do what our grandparents "and great-grandparents had to put up with?

"We don't have to do that anymore.

There's America."

My great-great-grandparents never would have imagined that there were choices.

You're--there's fate.

You're born into that situation.

That's where you're gonna live.

That's where you're gonna die.

Diner: What do you do once you get the idea that you want to go to America?

Your relative will send you money, and you have to then make your way from whatever little town you're in to the West, where there are railroads, that they could hop onto a railroad.

Kobrin: It is illegal to leave the Russian Empire unless you have the proper papers.

Most Jews do not have the proper papers, so many sneak over the border.

It's called "stole over the border."

They didn't go during the day.

They went at night.

And then they would travel to the ports.

Narrator: In the early 1800s, there were no actual immigration boats to America.

Instead, Jews purchased tickets to travel on sailing ships transporting cargo for a journey that could take up to three weeks.

While some could afford tickets on the upper decks, the majority of immigrants traveled in the spaces between decks or at the bottom of the ship.

This was known as steerage.

Kobrin: Everyone is living there.

It smells in a nauseating way.

The ship--it moves all the time from side to side.

It was just crowded, unpleasant.

People were sick on the boat.

And if you were sick, you were all sleeping together in one area.

That's why many people would catch illnesses.

If you were sick and you died on the boat, you would die, but then you would be thrown overboard.

[Horn blows] Diner: When it really has a huge bump, starting in the 1870s, is not surprisingly, because we have the transition from sail to steam.

The steamships carry enormous cargo of immigrants.

And, in fact, the immigrant trade by the 1870s and 1880s becomes big business.

And so it's in all sorts of people's interest-- the steamship companies, the rail companies-- and also, by the way, the Americans, because they want white people to fill the continent, as it were-- to fill the steerage with immigrants, and they almost don't care where they're coming from.

Marrin: I know a lot about that journey directly from my mother.

The boat she was on was called the "Zealand."

It had four levels, three for the higher-paying passengers, and the fourth level at the bottom of the boat, the steerage level, was for people like her.

And they all slept in hammocks.

The trouble is, when the sea got rough and people started throwing up, if you were on a lower hammock, you were in trouble because it landed right on you.

They would not have left if it wasn't awful.

They left.

They were in steerage.

So clearly, they weren't very rich.

If I were them, in a not-so-great life, in a place that hated my people, I, too, would have taken whatever shekels I could pull together and jump under a boat and get to America.

Narrator: While the overwhelming majority of Jews came from Eastern Europe and Russia, a smaller number, some 50,000, came from Greece, Turkey, and Syria.

Rabbi Marc Angel: The situation in those parts of the world was terrible.

There were wars.

There was poverty.

There was discrimination.

And, more than anything else, there was a new dream: America.

And suddenly, word came to the Old World, "You know what?

In the United States, "you can get jobs, you can make money, "you could have a family, you could go to school.

You have opportunities.

You don't have them here."

And so a number of the young bachelors and young single women had the idea, "Why don't we try a new life?"

My grandmother, Romey, used to tell us when she left and she said good-bye to her parents-- and she knew then she would never see them again-- and the parents said, "You have to go to America because there's no future for you here."

And the parents knew they would never see their children again.

Those people were made out of material that-- you don't see that anymore.

They were gutsy people.

They were people who wanted to make the world a better place for themselves and do everything in their power to make it better for their children and for their grandchildren.

It was--it was awesome.

Woman: My grandmother was born in America, so her mother came here.

I never thought beyond her mother, my great-grandmother.

And now I think about the generation before that.

I think about my great-grandmother's parents, who saw their daughter leave with her children from Warsaw to get to America.

That's what I think about.

And I think about how they had no idea that there would be any future for their family, for their bloodline, or for the Jewish people.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield: No, I can't imagine what it must've felt like when you stood at that rail siding or you stood at that port and realized it was the last hug and the last kiss you would probably ever get.

Maybe that was the way even the group that stayed kept faith with the future, is they offered their kids to go on that journey that they couldn't take.

Narrator: By 1920, some 2 1/2 million Jews had come to America, each one with a story, arriving to face a new world and a new land, exhausted from travel, with a future that was entirely unknown.

Stanislawski: It's very scary.

We tend to think it's so easy.

They come, and then they're workers in a sweatshop, and then they own a penthouse on Fifth Avenue.

It doesn't work that way.

It's a horrible, dislocating experience to move to a place, to leave everything behind and move to a place where you don't know your way around, you don't know the language, you don't know the culture, and you don't have the moorings of traditional society.

It was really a fending-for-yourself kind of situation in the earlier decades.

Slowly, there grew up these immigrant aid societies that began to provide services to the incoming immigrants in order to help them survive.

And those serve as an enormous bulwark against this alienation.

You get synagogues.

You get loan societies.

You get a whole network of agencies that are there to help you.

Narrator: Many of the first to arrive became peddlers, calling on connections from their old hometowns or the communities they'd found in the United States.

Others worked in the garment industry, known then as the needle trades.

Almost all of them would send money home to their families.

Diner: Every letter that contains money is the biggest advertisement for America.

It's not only that they're sending back money in their letters, but they're paying the fare of brother number one and then brother number two and then brother number three.

And then they'll bring over sisters, and they'll bring over cousins.

And so they reconstitute pretty significant elements of their family.

Woman: People were receiving letters from people who had already gone to New York, for example, or maybe they'd even gone to Milwaukee or they'd gone to St. Louis.

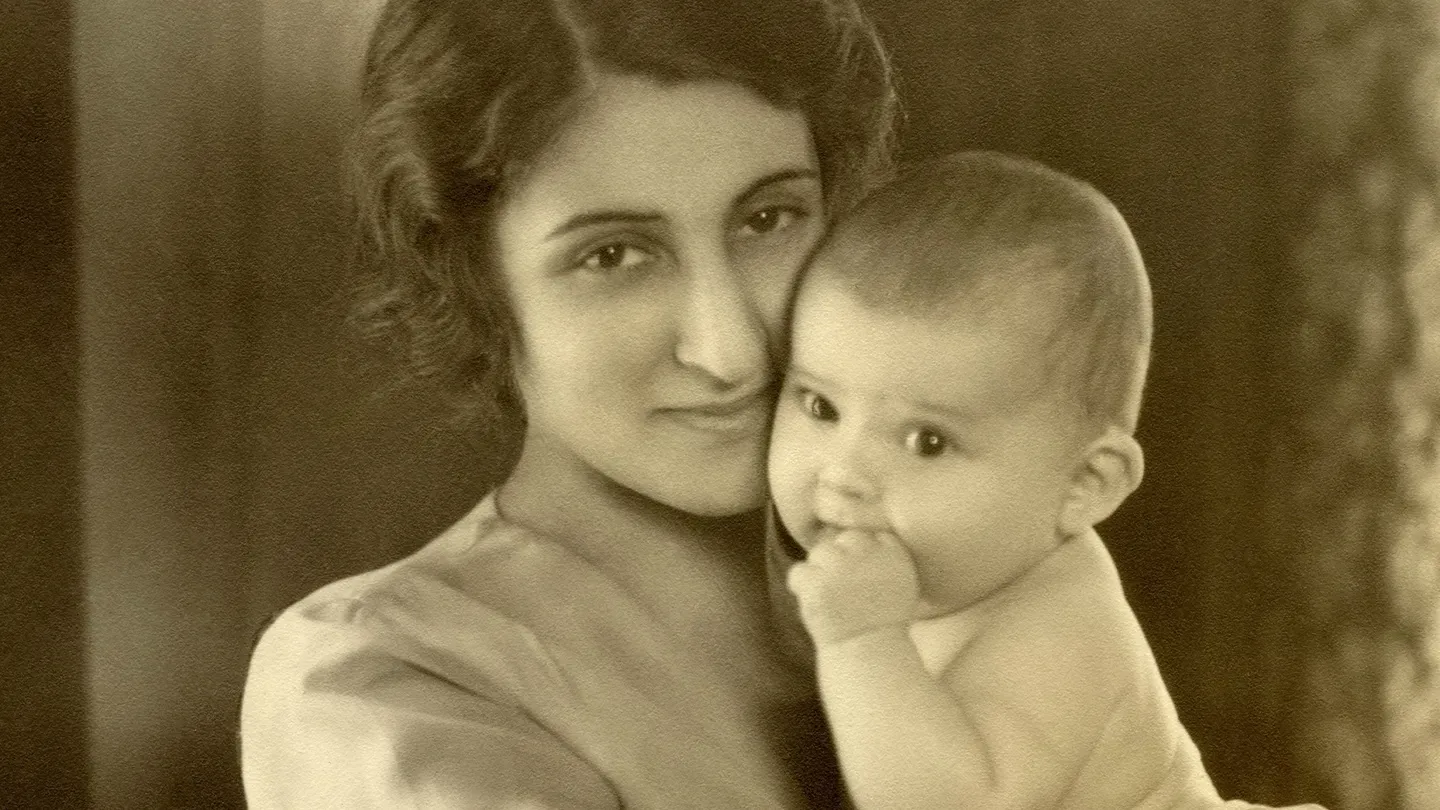

And these are relatives, these are neighbors who took themselves to a photography studio, borrowed a set of clothes and a nice hat to put on, had a nice screen behind them, took a beautiful picture of them in America, sent it home.

And so people thought, "Wow."

[chuckles] "They look great.

They look like a prince.

I'm going there."

Little did they know that once the guy was done with his shoot at the photography studio, he would put on his regular old clothes and his rags and walk out.

But that was a business.

You wanted to tell the people back home that you were doing well.

Rabbi Malka Drucker: My great-grandmother came penniless, illiterate, not knowing the language-- to this country with eight children-- my grandmother started working when she was four years old, doing work in the house of threading little Christmas cards to put on presents.

And my other grandmother went to work in a tobacco factory when she was 12.

On my dad's side, they got into textiles and dead people.

They started a cemetery that's still thriving in New Jersey, still family-run.

They got into shmatas and dead people.

Seems like two things that will never go out of style.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield: My mother's father's mother, she came here and very quickly sized up that life in America was going to be different than life in Hungary.

She separated from her husband.

They got a divorce.

She went into the real estate business for herself.

If she could find a room to rent for 50 cents, she'd rent it, and then she'd go on the street and find someone who'd rent it for 75 cents.

She'd take the 75 cents and find a 75-cent room.

And then she'd be on the street looking for someone to rent it for a buck.

Marrin: My grandpa, Zaydeh Gershon Leyb, was very...exploratory in how he thought of opportunity.

He had a candy store.

And it bored him.

And all of a sudden, I don't know what he did to create this opportunity for himself, but around that period, there was a Baron de Hirsch Fund.

It was to give Jewish people the opportunity to be landowners.

My zaydeh said, "A farmer?

I want to be a farmer."

And he accepted land, about 25 acres, and Zaydeh had a dairy farm-- not a whole bunch of cows--12-- in Ulster County.

I think they were the only Jews.

But here was the strange thing that I could never answer: they had left Europe to a new land, new opportunity, and yet, when they settled in Ulster County, it was as if they were in Russia.

The clothing was still the same.

The language was Russian.

The language was Yiddish.

English wasn't heard.

The only two English words that my grandfather knew was "nice girl."

When he patted me on the head, he would say, "Nice girl."

Narrator: As more and more Jews came to America, they fanned out across the country, building synagogues, getting educations and jobs, starting businesses, and creating communities.

In the 1920s, things changed.

A recession after World War I and the Red Scare led to a wave of xenophobia across the nation.

In the public discourse and among politicians, Southern and Eastern European immigrants were considered ethnically inferior, a drag on the economy, unable to assimilate into American culture.

What followed were a series of laws passed in 1924, which brought Jewish immigration to a near halt.

Jews who had hoped to come to America saw the doors close, and American Jews who'd planned to bring over extended families could not.

1933 marked the rise of the Nazis and, soon after, severe persecution of Jews in Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia.

In 1939, World War II would begin, and Jews would be persecuted across Europe, forced into ghettos, and shipped to concentration camps.

Despite frantic attempts by Jews in America to help Jews in Europe find refuge, the U.S. made few accommodations.

In the end, the effect on American Jews was marginal, but for those seeking escape from Europe, it was a death sentence.

During the war, by some estimates, fewer than 150,000 Jews were allowed into the United States, while some 6 million were killed by the Nazis.

Many consider this period to be the darkest chapter in America's immigration history.

After the war, America continued many of its firm policies on immigration, allowing in only 150,000 more Jews.

Can you imagine us?

OK, we went bananas.

We were all so excited seeing the Statue of Liberty.

This happened to be a beautiful day.

You see Manhattan on one side; you see New Jersey on the other side; or you're on the river, on the Hudson River.

It was just unbelievable.

Berger: I remember getting off the boat, and I remember a car ride to our hotel.

And I remember my mother not being quite happy because she thought she was coming to the city of Oz.

She didn't use those words, but, you know, she thought it was going to be the Emerald City.

And instead, she saw clotheslines hanging-- I think they probably went through a tenement area, and she saw tenements, and she saw dilapidated buildings.

Said, "This is what I left Europe for?"

Holocaust survivors are always depicted as grim and gloomy, and they were that way at times.

How could they not be?

But my memories are of refugees getting together, telling stories of the Old World, laughing a lot, having a schnapps.

And they would talk and tell stories about the Old World, about their families, and then I remember a lot of laughter.

Narrator: While the years following World War II brought much of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe and Russia to a close, the same period began a new chapter of Jews coming to America, this time from the Islamic world, across the Middle East and North Africa.

These were lands where Jews had lived for centuries.

Woman: Jews settled in communities throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

In some cases, for instance, in the case of Iraq, which is probably the oldest Jewish community in the Middle East, they were there for thousands of years, since biblical times.

It's difficult to generalize about the experience.

It just really differed from place to place, from time to time.

In Morocco, Yemen, Jews lived in relative security, but lived more simple, traditional lives, sometimes in small, rural hamlets, with traditional professions as craftsmen, as peddlers.

In some cases, notably Egypt and Iraq, Jews were very assimilated.

They were integrated into government.

They held positions of power.

They were ministers.

They were journalists.

They were writers.

They were musicians.

They were filmmakers.

Egypt and Iraq are often looked at as the most successful examples of Jewish integration into Arab society.

Woman: Baghdad through a child eyes, was beautiful date trees.

And I could see from the window the dates falling on the windowsill.

And we used to sleep on the rooftops in Iraq, and I used to count the stars.

The sky was clear.

And my father was very superstitious.

And he used to tell me, "Sanuti"-- because that was my nickname-- "stop counting stars.

It's bad luck."

When things were still good, the Jewish community used to take out the boats along the shores of the Tigris River at the crack of dawn, when it's not too hot.

And the river had a very distinct, delicious smell that I still can remember.

I don't know what it is, but I think smell etches the memory, because I still can smell it, and it wasn't just a few years ago.

Woman: There were, once upon a time, 80,000 Jews who lived in Egypt.

And they were a part of every sphere of society.

They were bankers.

They were lawyers.

They were even Pashas.

They'd been advisors to the kings.

When you think about the years, the 1930s, the 1940s, when my own parents were coming of age in Cairo and when so many Egyptian Jews were flourishing, that was precisely the time when, not so far away in Europe, Jews were experiencing horrific persecution-- pogroms, attacks, ultimately, the Holocaust.

But here in Egypt, it had been relatively safe and embracing.

Man: It was a wonderful world to grow up in because it was totally multicultural, multinational, multilingual, multi-everything.

How everybody tolerated everybody else-- I have no idea how they did it.

It's--there was no melting pot ideology.

It was just that everybody happened to be living together.

So you knew, among other things, what a church was like.

My Christian friends knew what a temple was like.

Everybody knew everybody else's language, so you spoke many languages, which was wonderful.

Man: We went to synagogue maybe three days a year, and we were not really a kosher family.

For us, Judaism was a lot more about the culture, a lot more about the family values.

My father spoke the Judeo-Persian dialect of Isfahan, my mother's family, that of Shiraz.

And so it was much more of a cultural identity than a religious one.

I mean, there were pockets of difficulty, pockets of anti-Semitism, that have a deep root in the Iranian culture.

But it was possible to grow up and be sheltered from it.

Aciman: In the family, especially among my grandparents and my great-aunts and uncles, they spoke Ladino.

It was a language that was spoken by the Spanish Jews.

And so, though they left Spain, allegedly in 1492, they continued to speak their own kind of Spanish, which is the equivalent of, you know, the Yiddish for people who come from Eastern Europe and Germany.

My grandmother used to call me... [speaking foreign language] Means "Beautiful child of mine."

Narrator: 1948 marked a change for Jews across the Middle East with the creation of the state of Israel.

While the new state was greeted with enormous enthusiasm, the countries in the Islamic world were enraged, and the Jews who lived in these lands began to see the decline and, ultimately, the decimation of many of their ancient communities.

That is the moment when it seems as though it's no longer going to be possible for Jews to stay in their ancestral homes throughout the Middle East.

In Iraq, for instance, almost overnight, it seemed, anti-Jewish legislation was passed.

Jews were fired from civil service jobs.

In most cases, they had to forfeit their property.

And so this entire group, they were essentially rendered destitute overnight-- just lost their life's work.

Narrator: While many Jews left their homes in the Islamic lands after the creation of Israel, the exodus continued in the years and decades that followed, as Jews fled persecution, political upheaval, and sought economic freedom.

I was playing hopscotch with my sister, who is two years older than me, outside, and two men passed by and said, "You Jews, we will slaughter you soon."

I remember my sister writing, "Israel."

And I remember my father having such a fit, and he said, "Don't you ever-- "If you want us killed, then write that name.

"Don't you ever articulate it or write it ever again."

Lagnado: You have to imagine Cairo as this very family-centric place.

You lived near your loved ones.

You lived near your relatives.

You lived near your grandparents.

And suddenly, almost overnight, it was over.

Nasser decided that Egypt was only a country for Egyptians and that we weren't Egyptians, even though we lived there, even though I was born there, even though my father thought of himself as completely 1,000% an Egyptian.

We had only the equivalent of a few dollars and were forced to sign a piece of paper saying we were leaving and we would never, never come back again.

And that's what we did.

And it was almost as if there was an erasure, an erasing of the life of the Jews of Egypt.

Most of our pictures we had burned even before we left, because if there was anybody on the picture that was, in the past, accused of being a spy, we would not want to be seen with them.

We left dressed as Arab women.

We were covered.

My parents specifically told us not to speak, because we had a Judeo-Arabic accent.

We were hoping to get over the border to Iran with a Jew-friendly shah.

A taxi driver came over to my father, and that taxi took us straight to the police station.

Altogether, we were in different prisons about five to six weeks.

Eventually, we did get a passport.

And I do remember, when that plane took off the Tarmac, that there was a sigh of relief, that we were free.

Lagnado: And that's one of the searing memories-- being in the harbor in Alexandria, waiting and waiting for our ship to come so that we could board it.

And pretty early in the voyage, my father, who I was sort of with, started screaming.

And he would scream these sort of two Arabic words... "Ragaouna al-Masr," which means, "Take us back to Egypt."

[crowd chanting] Narrator: The immigration from Iran came later, in 1979... as the Islamic Revolution arrived with its new leader, the Ayatollah Khomeini.

Under his regime, many Jews were seen as loyalists to the shah or as Zionists.

A mass exodus ensued with thousands of Iranian Jews fleeing, many to the United States.

Sarshar: My father got an anonymous phone call, telling him that it's time for him to pack up his family and leave because "he was a filthy Jew, and the country no longer had any room for Jews."

That night, my mom came to my room.

I'll never forget it-- she was crying and told me that I have to pack because "We're leaving tomorrow," and I'm not allowed to call any of my friends to say good-bye.

And that was the last time I was in Iran.

Narrator: Whether fleeing lands where they were no longer welcome or seeking better lives, the Jews from the Middle East and North Africa all had to start anew, learn a new language, a new culture, and new way of life.

But indeed, this has always been the story of America.

Aciman: I came to the States, and immediately, I found a job as a mail boy at Lincoln Center, and I just realized that this is amazing.

And I would speak to all these people.

I saw Leonard Bernstein, who I got to know.

I got to know William Schuman, the composer.

I mean, it was really amazing.

And for three months, I was a mail boy and loving New York.

It helped me adapt here in the easiest possible manner.

My mother had a job as a clerk in an office at a very elementary level, and my father worked as an employee.

He had never been an employee in 40 years, so he felt very uncomfortable, very resentful.

But they put up with it, and they cobbled lives for themselves, and invented some kind of way to continue being who they were without necessarily confronting the world outside of their apartment.

My family ended up in this little, remote part of New York called Bensonhurst.

It was kind of an entire universe of other immigrant Jews.

My family began, I think, deteriorating from the time we arrived.

And, you know, that's what-- these memories make me look askance at the notion of the American dream, because the American dream is not supposed to be about the dissolution of a family.

But in my case, it-- in our case, it happened so quickly.

My sister was in America, and what do young girls do in America?

Well, they leave home.

You don't do that in the Egyptian Jewish culture.

You don't do that.

So to the horror of my parents, she moved out.

She left home.

She didn't move very far.

She moved to Queens.

But she might as well have been light-years away.

My parents, I think, never made their peace with America, certainly not my father.

Sarshar: There was many, many years with everyone just heartbroken over the fact that we were a community in forced exile.

Everybody wanted to make sure that you always told everyone that we're not here by choice, that we were kicked out of our country, we had no option but to come here.

Parents were petrified of the value systems here, that their children were going to grow up without the strong family connection and the bond that assured their comfort at an older age.

Aciman: Despite the fact that most of our children will not be able to find jobs and may come back home after college, it is still a country where opportunity is at least perceived as present.

In the rest of the world, it's not there, certainly not in Egypt.

The sense that the future is not closed and locked to you is very important.

It's a very liberating feeling, and I've always had it in America.

Being here really provided the whole community with a tremendous amount of opportunity, you know, things that were not necessarily possible back in Iran.

All of a sudden, we all-- we came to a country where there were no limits.

Some of the members of our community here have acquired a kind of business and financial success that they couldn't have possibly dreamt of in Iran.

And others were able to educate themselves in a way that was probably not really possible for them back in Iran.

And they've had the freedom to be Jewish.

I mean, we--we are now-- my generation is a generation who is unburdened with the concern of whether we can tell people we're Jewish or not.

Narrator: In the late 20th century, and now in the 21st, America has become home to many more Jews.

Despite often restrictive U.S. immigration policies, these new immigrants have come from the Middle East, Asia, even as far as Ethiopia.

In the late 1980s, more than 100,000 Jews immigrated from the collapsing Soviet Union.

Today, America is home to nearly 7 million Jews who live throughout the country.

The Experience of the Jews in America is unprecedented in Jewish history.

Nowhere in Jewish history, at no time in Jewish history, have the Jews been so successfully-- economically, politically, social-- have the Jews been so integrated into the society on all levels.

Berger: I always felt America had been a haven for my parents.

You know, they had come from a Europe where they were murdering Jews.

They came here and didn't experience that.

It really was a country that-- maybe "welcome" isn't the right word, but certainly accommodated immigrants and understood them, because everyone has an immigrant in their background, so there was always an understanding of the immigrant plight.

My grandparents, they-- they wanted us to speak English.

They didn't want us to be Old Country.

They wanted us to be successful American people.

But at the same time that our grandparents wanted us to be Americans, they wanted us to retain the loyalty to our traditions.

But many have not--do not.

The American power of assimilation is very, very strong.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield: You have to remember, I grew up in a home in which I heard almost no Yiddish.

It was very American.

My mother grew up in a home where Christmas trees were put up, not menorahs, in which Easter egg hunts were a bigger deal than Passover Seders.

But I want to be clear, that had nothing to do with not loving being Jewish.

They were passionately Jewish.

It's who they were through and through.

I think there is a very strong gastronomic memory and a gastronomic identity.

And, you know, some people say, "The only part of me that's Jewish is, you know, is gefilte fish" or whatever.

What comes back, you know, are the smells and the tastes and the food from my apartment and my mother's kitchen and all that stuff.

I mean, the-- the chopped herring, the p'tcha, the verenikas, the borscht-- fleischkuechle borscht was like ambrosia.

Rabbi Marc Angel: I first came to New York in 1963 as a freshman at Yeshiva University.

We have dinner in the dorm cafeteria, and there's a little brown glob on my plate-- so I ask the guy next to me, "What is that?"

"What do you mean, what is that?"

"What is it?"

"It's chopped liver."

I never saw chopped liver in my life.

Next day, they served us this cholent.

I never saw cholent in my life.

They served us a kugel.

I never saw kugel in my life.

All the food that we had, everything was brown.

The roasted chicken and kugel and cholent and gefilte fish and-- honey cake for dessert and tea, everything's brown.

[scoffs] In our world, everything was colorful-- bright vegetables, salads.

When I first brought my wife to meet my parents in Seattle, my wife counted, at one meal, she had 13 different vegetables, half of which she never saw before in her life.

I have to tell you that the meals I lusted for the most, to my embarrassment, are Swanson dinners, TV dinners.

Those things never existed in the rest of the world, but you've always seen advertised-- those meals advertised in magazines.

You had no idea what they were, and eventually you can go out to the supermarket and buy them.

So how could you resist?

So first of all, it is a miracle that after a number of generations in America, Jews are still Jewish.

How observant?

You know, there's-- there's a variety of levels.

But Jews are still Jewish, which is an amazing thing.

That deserves a whole-- a whole show on its own.

But the fact that the observance is growing and the study of Torah is growing, nobody expected that.

My grandfather didn't expect that when he came to America.

He gave up on me.

[laughs] Rabbi Malka Drucker: My family, personally-- I knew I was a Jew.

I knew it was a good thing to be a Jew.

It was purely ethical.

To be a Jew meant to be a Democrat.

To be a Jew was to be against McCarthy.

To be a Jew was to believe that life wasn't fair and that we were here to make it more fair.

Do you hear the word "God" in what I'm saying?

No.

"Torah"?

No.

"Ritual"?

No.

That wasn't what it was to be a Jew.

It was to behave in this highly ethical way.

And it wasn't till much later in my life that I came to appreciate ritual.

Marrin: Zaydeh was a man with a big, gray beard dressed like a Russian peasant.

One day, I was looking through the doorway as he was praying.

And the light was coming through the window above the stand where the Torah was and lit him up.

He glowed.

I stood there next to him.

Nobody else was around.

And I absorbed that spirit at a level that I didn't realize was happening until I got older.

I love being part of something.

Even if we've never met, your last name is Goldberg, my last name is-- ambiguous, Greenleaf, but we know that we're Jews, and we know that there's a similarity there.

And I like being part of something bigger than I am.

Now I face an interesting situation because my husband's Catholic.

People say things like, "Well, how are you going to raise your kids?"

I don't even know where to begin.

In my case, it's further complicated.

They're adopted.

One's Cajun.

One's African-American.

There--there's a lot of things there.

But I want to make sure that being Jewish isn't lost on them.

Greenfield: I was born a Jew.

My family died because they were Jews.

And my father's words saved me more than any words I ever spoke.

My father should rest in peace.

He said, "You survive.

"You honor us by living, not by crying.

"The future "you think about every minute.

That would be our greatest honor."

And I live by that.

For my great-grandparents, it was like that old song says, "We got to get out of this place if it's the last thing we ever do."

For my grandmother, it was, "We're going to make this place home.

"For the first time in 2,000 years, we're going to feel at home in the Diaspora."

And for my mother, it was, "I'm going to be so at home that I will take pride "even in those rituals I don't practice, because that's what I can give my kid."

And for me, it was to embrace some of those rituals, but never at the cost of failing to appreciate the depth of Jewishness, the depth of faith, the depth of everything good in those previous generations.

Federbush: I am thanking God almost every day for being here.

Almost every day, every time I think of it.

And I'm trying to impress upon my children how wonderful this country is, and they know it.

And there isn't a moment that does not change the fact-- the love of my country-- of this country.

And this is the way I'm going to-- I'm going to die this way, and--and on my-- and on my tombstone, it will say, "Melvin loves this country."

Hirschfield: I remember when I chose to start wearing a kippah.

Right?

Yarmulke.

Skullcap.

Call it anything you want.

We walk in to my great-grandmother's home, and she was like the queen of the family.

She lived to be 104 years old.

And I'm now 12, and have decided to start wearing one of these.

I bend down to kiss her.

And as I do, I feel, like, two talons grab onto my head and tear the kippah out of-- bobby pins and all-- right out of my hair and throw it on the ground.

And she looks at me, and she says, "I did not come to America for that kind of silliness."

And I'm now 12 years old, newly observant, surrounded by a mother, a father, a grandmother, a grandfather, three siblings, two great-aunts, and my great-grandmother.

And I'm like, "What am I supposed to say?"

My mother stepped in, and she said, using one of the few Yiddish words I ever heard growing up, "No, Bubbe!"

That's the Yiddish word.

"You came to America so he could choose to if he wanted to."

♪

Support for PBS provided by: