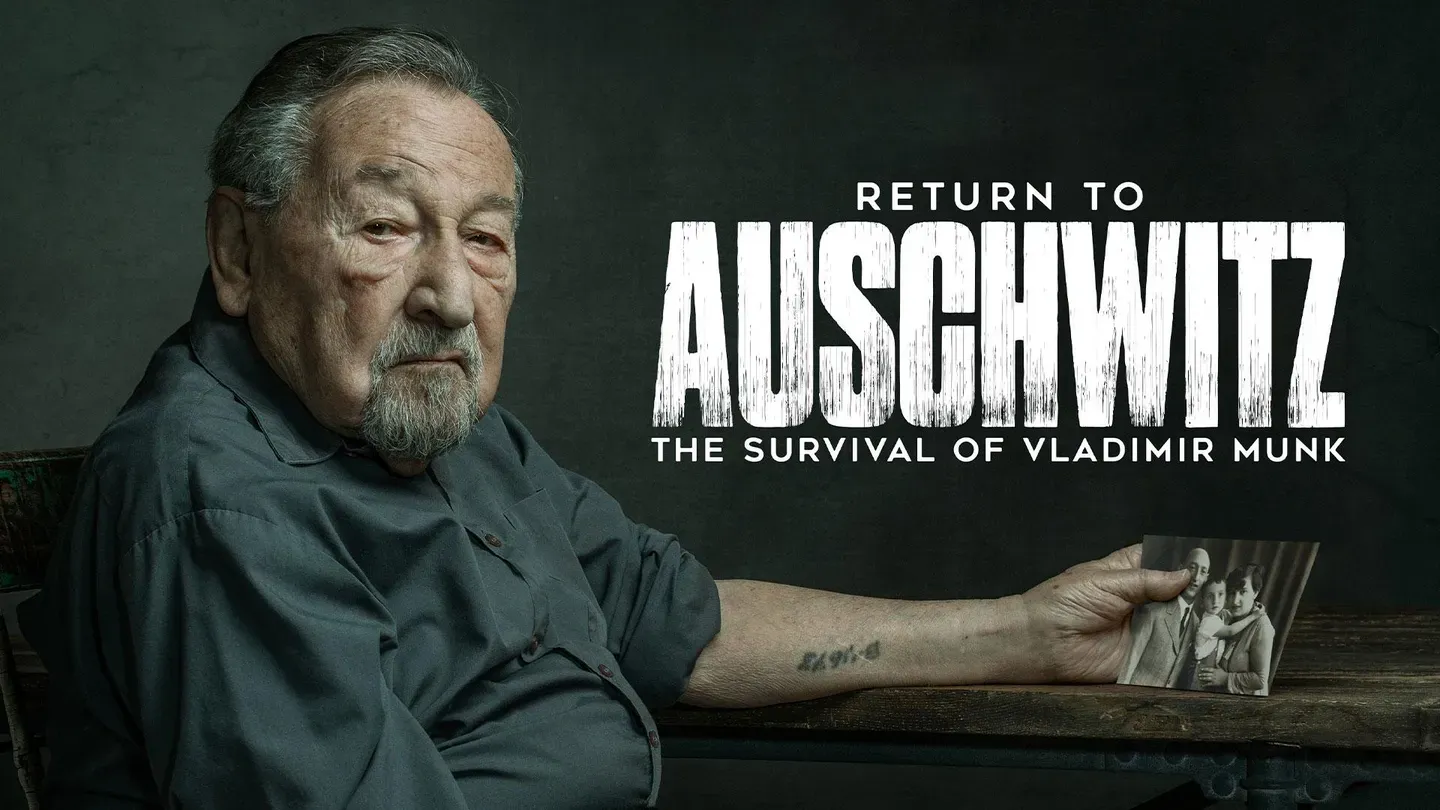

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk

Special | 56m 30sVideo has Closed Captions

Holocaust survivor Vladimir Munk returns to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk is a moving documentary of Czech Holocaust survivor and retired U.S. professor Vladimir Munk. The film followed Vladimir in 2020, at age 95, as he returned to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp, one of the camps where he was held prisoner during World War II.

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk

Special | 56m 30sVideo has Closed Captions

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk is a moving documentary of Czech Holocaust survivor and retired U.S. professor Vladimir Munk. The film followed Vladimir in 2020, at age 95, as he returned to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp, one of the camps where he was held prisoner during World War II.

How to Watch Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(soft sorrowful music) - I have never been in Auschwitz since 1945.

I don't know how I will feel when I'll be back.

Not that I try to forget, but I try to suppress the thinking about the Holocaust and of my past.

I try to live a normal life.

Sometimes when I am thinking about the past, it's difficult thinking.

I am a little bit afraid that when I'll be standing there and realize that over 30 of my really close relatives, including my parents, perished there, I'll feel a little bit low.

I think that for people, it's important not to only realize that it happened, but to preserve the memory of it for the future generation who do not know anything about it, to learn about it, to see that it really existed.

I'll be 95 next month.

Sure, there is some risk because people of my age die for no reason at all, just for the age.

I may die there.

That's a risk that I have to take.

(intense poignant music) Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk was made possible in part by the generous support of the following people.

(soft piano music) (keyboard typing) - What makes any one person a survivor?

Is there a characteristic, an idiosyncrasy that might lend itself to survival through one of history's most horrific campaigns of mass genocide?

I wrote these words as the introduction to Vladimir Munk's biography, which ran in a New York state newspaper in 2019.

He told me about his childhood growing up in Pardubice, Czech Republic, his life as a Jew during German occupation, and his family's deportation to a concentration camp.

When he was tired of talking, we threw back a shot of Slivovitz, Czech plum brandy, shook off the darkness, and laughed and talked of lighter things.

I first met Vladimir at Lake Forest with his wife Kitty at the time.

My singing partner and I used to play there for the seniors.

And Tim introduced us, and Vladimir invited us back to his apartment for his standard hospitality, a shot of Slivovitz.

That was the beginning of our friendship.

I realized that my friendship with Vladimir was getting a little deeper.

When I started going on my own, we started discussing the Holocaust.

I knew six million people had been murdered.

I had never known one person that had survived.

- When you come every Sunday afternoon to talk and drink a little bit, you become good friends.

- [Julie] One day, a letter arrived inviting Vladimir and a companion to attend the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi extermination camp in Poland.

He would be part of the survivors' delegation.

It seemed perfectly natural for him to decide that, yes, he would attend this historic event.

- Julie, would you like to go to Auschwitz?

I'd love to.

That was it.

- [Julie] It was a place he thought he would never return to, a place of horror and sadness.

- My father decided to go back.

And my first reaction to that was somewhat negative, to be perfectly honest.

I feared for his health at his age of 95, and I also feared for the emotional impact a visit like that might make.

- [Julie] I was honored that Vladimir asked me to accompany him on this journey.

I knew there would be challenges.

As his companion, I would have to be mindful not only of his physical safety, but also of the emotional toll returning to that horrible place might have on him.

I had to make the trip.

His life story needed to be told.

(upbeat polka music) Czechoslovakia grew to be one of Europe's most prosperous states between the First and Second World War.

In that golden era on February 27th, 1925, Vladimir Munk, the only child of Karel and Hermina Munk, was born.

- My mother didn't have to work, and she has a maid, and she joined a lot of social clubs and sport clubs, played tennis, taught me how to ski.

My father, every Sunday morning, he went to a coffee house.

There he met his old friends, and he read magazines and newspaper, drink coffee, and enjoy life.

- [Julie] Vladimir's father, Karel, had been a distinguished member of the Czech Army.

After completing university, he was appointed head chemist in an industrial distillery.

The family made their home in a comfortable apartment on the property.

- My parents, I don't know for what reason, they bought a fox terrier.

The dog's name was Chiggy, and it was the only member of our family who survived the war.

I met with the dog after the war.

My family was traditionally religious because their parents were religious.

So they were religious, but their wedding was not in synagogue.

It was in city hall.

They belonged to the Jewish community in Pardubice.

They had many friends who were Jewish.

I had to have bar mitzvah because I belonged to the Jewish family.

- [Julie] And so young Vladimir, in his first hat and long pants, his aunts and uncles in attendance, completed the ritual coming-of-age for Jewish boys.

The world outside the bucolic corner of Pardubice was filled with unrest.

Adolph Hitler had been threatening to take the Sudetenland, a region of Czechoslovakia occupied primarily by ethnic Germans.

To appease Hitler and prevent war, leaders from Germany, France, Italy, and Great Britain signed over the territories to be annexed by Germany on September 29th, 1938.

Prime Minister Jan Syrovy announced, "We are abandoned."

Vladimir and his family would soon feel the same.

In January of 1939, Adolph Hitler proclaimed that if a world war were to break out in response to his domination of Germany's neighboring countries, it would result in the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.

This threat drove many Czech Jews to flee their homeland.

More than 14,000 fled before the German tanks rolled into Prague in March.

- [Vladimir] Jews were not permitted to attend any public actions.

We couldn't go to the movies, to theaters, to the sport events.

We were not even permitted to be members of any clubs.

- [Julie] Reinhard Heydrich was a high-ranking Nazi in charge of the Czechoslovak region.

He directed the first round-up of Czech Jews transported to concentration camps in November of 1941.

He was known to Hitler as the man with the iron heart.

In May of the following year, members of the Czech resistance made an attempt on Heydrich's life.

Critically wounded, he died a week later.

(explosions roaring) In retaliation, German forces destroyed entire Czech villages.

The fallout was felt throughout Czechoslovakia.

Vladimir's father lost his job at the distillery.

- I was not permitted to go to the school.

I had to start working as a laborer.

And then we had to move to a small apartment.

There were problems with food because we were not permitted to buy butter, to buy eggs, to buy milk, to buy some types of meat.

- [Julie] Isolated in a ghetto without walls, Vladimir and his family endured discrimination, racial slurs, and a growing fear of what would come next.

- In 1941, we were forced to wear the Jewish star.

Some of our so-called friends stopped talking to us.

- [Julie] A diary started by Vladimir's maternal grandmother, Emily Gesmay, survived, which tells the story of what became of Vladimir's family.

September 9th, 1942 is marked with this passage: "This was a fateful year for the whole family, terrible persecution of the Jews."

Emily was deported at age 78, totally blind.

Entire families were sent to Terezin concentration camp or destinations unknown.

In December, 1942, the youngest child of the Gesmay family was deported with her family, Hermina Munkova, husband, Karel Munk, and son, Vladimir Munk.

Terezin, renamed by the Germans as Theresienstadt, in the Czech Republic was a military fortress built in the 1800s.

It consisted of a citadel called the small fortress and a walled town for protection against invading troops.

Years later, the German SS would find the town quite well-suited for their needs, a holding place for Jews from Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Austria, and Germany.

The small fortress was used as a prison in which inmates would be tortured and executed.

- We arrived to a railway station that was about one mile away from Terezin, and then we marched slowly in the direction of Terezin.

We were assigned some work.

My father disappeared in Magdeburg Barracks, and Magdeburg Barracks was the central administration for Terezin.

He never talked about what he was doing.

Later, from a group of Soviet historians who immigrated to Israel and studied Terezin, that my father there was underground movement in Terezin and that my father was in the central cell.

And apparently that was why we were protected so long because most of the people from Pardubice transport were a long time before they were sent to Auschwitz.

- [Julie] Vladimir was assigned a job as a locksmith.

The walled city with a pre-war population of 5,000 needed constant upgrades to its infrastructure to accommodate as many as 55,000 inhabitants at the height of the war.

One year passed and another began for Vladimir Munk and his family in Terezin.

The cycle of life occurred within its walls just as it did in the outside world.

Couples married.

Babies were born.

People died.

People fell in love, including Vladimir.

Kitty Lowi was born in Teplice in the Sudeten region.

Her parents and her brother, Hans, were sent to Terezin by special transport on February 16th, 1943.

Kitty was sent to work in vegetable farming, forced to work outside in all kinds of weather.

The only perk were the vegetables she was able to smuggle under her dress at the end of the work day.

- My parents did meet in Theresienstadt when they were quite young.

I think my dad was 17.

My mother was about 14 at the time.

- I was young.

For me, it was adventure.

I was not hungry because my mother was connected with the kitchen.

And it was my first girlfriend there.

So we had a lot of fun.

Terezin was basically a place of young people because the old people didn't survive.

The government decided very early the most important thing is to save the young.

So the children had two special houses.

They had certain education there.

They had better portion of food.

Finally, they died too, because toward the end, they sent everybody to Auschwitz.

But during that life in the Terezin, they had certain advantages.

- [Julie] Through a beautification program, they created images of the camp for an International Red Cross inspection and a propaganda film that could not have been further from the truth.

In the film, Jewish residents appear healthy, happy, and well-nourished, enjoying cafes, sporting events, and a children's play.

- [Vladimir] About 140,000 people was deported to Terezin.

Out of these, about 33,000 died in Terezin and about 88,000 were deported, most of them to Auschwitz.

Less than 10% survived.

On October 1st, 1944, my father and I were told that we are going a little bit farther from Terezin to build another labor camp.

About 70 hours later, we ended in Auschwitz.

(haunting music) Auschwitz, I said, "Oh."

I knew that Auschwitz is a bad concentration camp.

Train stopped, and then the kapos came, opened the door, came in, said, "Out, out, out.

Leave everything, leave everything."

My father was in the front of me stopping in the front of Mengele and answering him something.

And then Mengele moved his right hand to the right.

So my father walked to the left.

That was last time that I saw my father.

I walked to the front of Mengele.

He didn't ask anything, showed to the left.

So I walked to the right.

It was like in another world.

We were marched, and on one side were a high-wire fence, and behind the fence were wooden barracks for women.

And women were running out.

They were all in the striped dressed.

They were shouting on us, "Bread, bread, bread."

And the moment they came close to the fence, the guard from the tower started to shoot them.

Terezin was like a spa compared to Auschwitz.

- [Julie] Vladimir's belongings were confiscated.

His head was shaved.

He was crudely disinfected, forced to shower, and given rags for socks.

There was one final indignity.

- Spelled your name.

He wrote your name on the index card and told the other guy the number.

And he had something like a needle in a piece of wood and very fast pricked many little holes in the front of the number on your forearm and then smeared it like with this Indian ink, black ink.

See?

Every morning we were forced to go out between the barracks and stay there, stay there, stay there.

They counted us and counted us again and counting us again.

We were freezing.

It was raining.

We didn't do anything, no work, no labor.

And there was a smell, a sweet smell all around.

And then there were, in the background were three huge chimneys, and a huge amount of black smoke was coming out of them.

And it smelled like burning meat.

And I asked a guy, "Do you know what happened to the people who are separated?"

You see the smoke there?

He went up the chimney.

So in Auschwitz, you didn't die.

You just went out up the chimney.

And that shocked me so much that I just got in depression.

My mother was sent to Auschwitz about October 14 or October 16, as I learned.

I believe that she went directly to the gas chambers because she was helping her sister-in-law with a small child.

They automatically sent a bunch of sweet little children to the gas chamber.

(haunting music) ♪ Ah, ah, oh ♪ ♪ Oh, oh, oh, oh, oh, oh ♪ ♪ Oh, oh, oh ♪ ♪ Oh, oh, oh, oh, oh, oh ♪ - [Julie] Vladimir was sent from Auschwitz to Gleiwitz, a slave labor camp, to repair rail cars damaged by Allied bombs.

Gleiwitz was known for its harsh conditions and low survival rate.

- What I remember from Gleiwitz is cold and hunger.

The German scientists calculated the food portion for the people who are working in these satellite camps.

They shouldn't last longer than three months.

And I stopped grieving because I was so hungry.

At the time, we didn't think about anything but food, and the second thing I thought about was I hated the Nazis.

I always thought, I have to survive.

I have to kill the Nazis.

I have to kill the Nazis.

- [Julie] Gleiwitz was evacuated as Soviet troops drew closer.

On January 8th, 1945, Vladimir and the other prisoners were led on a death march to Blechhammer concentration camp.

- [Vladimir] We marched for two days.

When you fell, they shot you.

They didn't let anybody stay behind.

- [Julie] At Blechhammer, having barely survived the death march, Vladimir fell into a deep sleep.

He awoke to an empty camp and the sound of machine-gun fire.

The Germans had evacuated, leaving Vladimir and a handful of prisoners behind.

- And there was totally empty concentration camp, but we couldn't find any food.

Everything was taken.

- [Julie] Venturing outside the camp, Vladimir came upon an abandoned house.

- We opened it, and we found fresh bread on the table.

I ate after two years, find a nice, good, fresh bread.

- [Julie] He made his way to Krakow, where he was hospitalized with pneumonia.

He recovered and was released without a penny to his name.

- And we made living by begging.

We took one street after the other and ring on the house.

We are from concentration camp, you see.

They invited us inside.

They gave us food.

They gave us some money.

(train chugging) When I was in the train coming back to Pardubice from Krakow, we stopped, I don't know what city it was, and there was a line of girls and young women who were sleeping with the Nazis.

So now they were punishing them.

When they caught some SS men or something, they shot them.

It was fine with me.

(suspenseful music) - [Julie] Vladimir reunited with his beloved Kitty in Prague, honoring the pledge they had made in Terezin.

They were married in 1949.

He enrolled at the Technical University in Prague, where his passion for biochemistry and microbiology would be ignited.

He graduated in 1950 with an MS in chemical engineering.

Three years later, he was awarded a PhD.

Vladimir accepted a position in the Central Research Institute for Food Industry and later moved to the microbiology department.

It was here that he began his research on microbiological production of enzymes useful to the food industry.

The department was soon recognized as one of the best in the world.

Vladimir would go on to file over 20 patents.

- My first memories of finding out that my parents were concentration camp survivors, I was about 10 years old.

My dad, while washing windows, cut a main artery in his arm, and he had a tattoo on his arm.

And I noticed the tattoo.

Up until that point, I really didn't think about World War II much.

It's not something that we discussed in the house very much.

When he was taken to the hospital to fix the cut and have some surgery, he was asked whether he wanted that number removed.

And he said no.

- In 1963, Vladimir joined the Czechoslovak Academy of Science, founding the laboratory of applied microbiology.

For his work on the production of microbial proteins by growth of yeast on hydrocarbons, he was awarded the State Prize of Czechoslovak Republic in May of 1968.

Three months later, the sound of tanks rolling into Czechoslovakia brought back flashbacks of the German occupation.

In August of 1968, Soviet Union and Warsaw-Pact countries invaded Czechoslovakia, cracking down on democratic reforms.

Vladimir was offered an opportunity to join the faculty of the State University of New York in Plattsburgh.

In 1969, when the new Czech government ordered Vladimir and his family to return, he refused.

The university supported his decision and changed his status from visiting to full-time professor.

Vladimir had left behind the country he once called home, this time for good.

He became a respected professor and mentor to many of his students.

He was recognized by them with the university's most prestigious Chancellor's Award.

When he was teaching, I think that he wanted the focus to be on teaching.

He wanted the students to learn, and he didn't want any distractions.

He didn't want the focus to be on him or his story.

- And I started to go to the schools only several years after I retired from the teaching.

Over 25 years, I visited local and regional schools.

I talked usually to the middle school and high school students.

I have hundreds of letters from them.

Some of are pretty nice letters when one students write, "I read a lot about Holocaust, but there is nothing like to get it from the horse's mouth."

- In 1996, Vladimir and Kitty were interviewed for Steven Spielberg's Shoa Foundation as witnesses and survivors of the Holocaust.

In 2015, Kitty passed after a five-year battle with Alzheimer's disease.

In January of 2020, Vladimir thought about this chance to finally return to Auschwitz.

- So it will not be very pleasant.

I mean, it will be depressing, We have to get a bottle of vodka and just wash it down.

(laughs) This is the last chance and a good chance to be there, you know?

We were surviving somehow.

(tense music) - [Julie] From the moment we got off the plane in Krakow, Vladimir was in high demand.

While we waited at the baggage carousel, Vladimir conducted his first interview on Polish soil.

It would be the first of many.

We had left Vladimir's apartment in Plattsburgh, New York 24 hours earlier.

(fast string music) - It's a special trip.

Thank you for taking the courage to come back 'cause we wanna learn.

We wanna hear from you.

- I doubt that I will survive.

- You will.

- Absolutely.

- [Julie] A news team from Vladimir's hometown of Pardubice had traveled from the Czech Republic to meet him.

Sarka Kutchtova and Tomas Bloch were waiting at the hotel to interview Vladimir.

Sarka had been in contact with Vladimir for months, hoping to tell his story on a Czech news program similar to 60 Minutes.

I could see that speaking in Czech lifted Vladimir's spirits and energized him.

After nearly two hours, I had to pull Vladimir away from his compatriots.

The next day is the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz at the camp.

It was going to be a long day, and he needed his rest.

(soft string music) After a good breakfast, Vladimir was eager to board the bus to Auschwitz for the anniversary ceremony.

We had heard sad news on the elevator that morning.

One survivor who had gone to the camp the previous day for a press tour had a heart attack and was in the hospital in Krakow.

His condition was unknown.

His family was in shock.

The drive from Krakow to Auschwitz would take about an hour.

The day's itinerary began with lunch and a group photo of the survivors' delegation.

As I looked over the sea of faces assembled for the anniversary photo, it was clear that this special group of humans had faced many challenges to be here.

Each lined face had a story of survival.

It was humbling to look out at them.

And I swelled with pride at the strength of my friend making the trip to be among them.

We boarded the bus again and traveled in silence across the street to the camp.

I realized the first irony of the trip.

The survivors would need to enter the tents alone, separated from their caregivers.

Vladimir looked so small and unsteady walking up the ramp.

Then he was swallowed up into the tent.

The event was televised around the globe, with millions of viewers watching as the survivors gathered in the shadow of the gate.

Dignitaries from numerous countries were in attendance.

Security was high, not just due to the presence of world leaders, but because the growing rise in antisemitism had sparked fears of violence.

The speakers spoke passionately about the need for the events of the Holocaust to never be forgotten.

- Do not be silent.

Do not be complacent.

Do not let this ever happen again to any people.

- [Julie] Vladimir sat for hours listening attentively on his headphones as the speeches were translated from many different languages into English.

He swayed to the chamber music that separated each speaker.

I watched him closely for any kind of emotional reaction, but it became clear that he had compartmentalized the formality of this event.

Would it be a totally different story the next day when we would walk the grounds of Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he had experienced unimaginable loss?

(gentle music) The next morning, a van departed the hotel full of Auschwitz survivors and their companions.

In just over an hour's ride, Vladimir would be at the camp where he had been held prisoner and where his parents and over 30 family members had perished.

What was going through his mind?

Would he recognize any landmarks?

Would we see where he was processed and given his tattoo?

Would it be too much for him?

His mother and father, aunts and uncles had no formal resting place.

They were more than likely among the many who were cremated at the camp.

Before the trip began, Vladimir had said it would be like going to a cemetery.

Would he feel that way once he was standing inside the gates?

As we passed a wooded area, he murmured, "Birkenau, the birch trees."

Birkenau was the German name for the Polish village Brzezinka, just a few kilometers from Auschwitz One.

The name stems from the Polish word (speaks in foreign language) or birch.

Upon seeing the iconic birch trees in the forest, Vladimir's memory was springing to life.

What other memories would this trip to the camp uncover?

Every moment had its cruel twin in a mirror held up to the past.

Would he disembark the bus and relive the selection process?

Was he regretting making the trip?

Did the thought of paying his respects to his parents and family members feel worth it as he set his foot on the soil of this terrible place once more?

Over 100 of the camp survivors brought here as prisoners in cattle cars when they were little more than children were about to leave the comfort of the charter buses to set foot once again on the grounds of the place where many had almost perished.

Almost 95, Vladimir was one of the oldest survivors on this journey.

Despite heart problems, he had traveled 24 hours to get here.

- Oh!

That's great.

What would I do without you?

- You already comfy in there?

- I'm very comfortable.

- [Julie] Setting foot on the ground outside of the gate to the camp was a terrifying homecoming of sorts.

No matter what happened over the next few hours, he was a hero in my eyes.

Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi concentration and extermination camp, was the largest of its kind and consisted of three camps, Auschwitz One, Auschwitz Two, and Auschwitz Three.

Auschwitz One began as a jail for Germany's political prisoners.

With Auschwitz Three, companies like IG Farben would capitalize on the slave labor of over 30,000 prisoners.

In 1941, the SS began expanding the original camp, branching out into the nearby village of Birkenau.

It would become the site of the Nazi's largest-scale prisoner extermination program.

Today, Auschwitz One and Auschwitz Two, Birkenau, make up the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Oswiecim, Poland.

The row upon row of pre-war brick barracks, or blocks, that make up Auschwitz One had originally been part of a former Polish Army compound.

The cobblestone streets lined with tall, thin trees had been left in their original condition.

In the early days of Auschwitz One, prisoners actually served their sentences and were released.

More buildings were added, and the modest two-story buildings were often made to hold upwards of 700 prisoners.

As many as 1,200 prisoners were crammed into the barracks at one time.

Auschwitz One evolved into its role as a concentration camp at first using inmates as disposable slave labor and later targeting groups felt to be a threat to the Reich.

We would begin our tour with our guide, Peter, in Auschwitz One.

Vladimir had been sent to Auschwitz from Terezin concentration camp along with his father in a series of mass deportations.

He was not a political prisoner and for that reason had never set foot in Auschwitz One.

The streets that day were crowded with survivors, their companions, and news crews from different countries.

The rough cobblestone streets made it difficult to proceed with Vladimir in the wheelchair.

He preferred to walk, no matter what the risk.

We followed the crowd and found ourselves at the infamous gate which marked the entrance to the camp.

The words on the gate, arbeit macht frei, translate to work will set you free, but it was a lie, one of many of the new arrivals at Auschwitz would be told.

That moment is etched in all of our memories.

It felt triumphant.

The 19-year-old young man who had survived Auschwitz- Birkenau had returned.

The Nazis had not won.

He was here alive.

He was a survivor.

- [Vladimir] (groans) Oh, oh, oh.

Oh, I made it.

- [Julie] You made it.

There was an exhibit Vladimir insisted on seeing which focused on the fate of the Bohemian Jews of which he and his family were a part.

The challenge of walking up the stairs was worth it.

The exhibit was in his native Czech, and his intimate knowledge of the fate and events which befell the Czech Jews brought out the teacher in him.

Soon he was leading the tour, and our guide was asking him questions.

The exhibit told the story of the Czech resistance and subsequent repression of the Czech Jews.

After the German occupation of the Sudetenland and creation of the protectorate, Vladimir's family attempted to emigrate.

All options were closed to them.

They could not escape.

A map depicts the concentration and extermination camps to which Jews were deported as Czechoslovakia was made systematically Jew-free.

Most were sent to Theresienstadt and later to their deaths at Auschwitz.

- [Vladimir] 18,400, and 1,500 survived.

- [Julie] And you're one of them.

- [Vladimir] Yeah.

- [Julie] An entire wall was filled with photos of early political prisoners.

We did not expect to find photos of any of Vladimir's family, but it was heartbreaking to see the sheer number of victims.

Each one was an individual, not a number, with a life, a family, and before the Nazis, a future.

(haunting music) (female vocalist singing) - [Julie] Now it was time to make the 3 1/2-kilometer trek to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

To prepare myself for what we might see at the camp, I had watched videos of the Russians liberating the camp on Yad Vashem's website.

Yad Vashem is the World's Holocaust Remembrance Center, a memorial dedicated to preserving the memories of the victims of the Holocaust.

I watched graphic videos depicting the camp's skeletal survivors.

First, they would have to overcome malnutrition and disease.

Then they would have to face the fact that, in most cases, none of their families had survived.

I feared for the toll his return to this evil place would take on my dear friend.

Neither Vladimir nor I had any idea what to expect.

There was no turning back.

The gate through which trains to Auschwitz-Birkenau passed is called the Gate of Death.

One cannot begin to imagine the terror that those who approached it must've felt.

In October of 1944, Vladimir and his father, Karel, were on one of those trains.

The trip from Terezin took 30 hours.

A hush descended over the train as it came to a screeching halt just inside the gate.

The doors to the train cars were ripped open, and nothing could be heard among the shouting of the SS guards, (speaks in foreign language), and the barking of the dogs.

(men shouting) Vladimir and his father had arrived in hell.

Now, Vladimir was standing just a couple hundred yards away from where he had stood 75 years ago, near the platform where he had waited his turn in line for the selection process under the cruel eye of Dr. Joseph Mengele, the same spot where he stood helpless as his father was sent to the left, and Vladimir was sent to the right.

For the first time in his young life, surrounded by a sea of tortured souls under a barrage of shouts and beatings, Vladimir was suddenly, totally, and utterly alone.

I had a flashback to my parents dropping me off for my freshman year of college.

After sitting through a welcome lunch and orientation with my mother and father, I could barely contain my excitement to get out of the car, say goodbye to them, and begin my new adult life.

I gave my mother the quickest hug, and without so much as a second look, ran up the stairs and out of sight, I took for granted the fact that they would be there for me in the future, for the day I married, the birth of my child.

There was a crack in the universe that stole all that from Vladimir.

In an instant, a level of cruelty was allowed that would prevent Vladimir from ever seeing his loving parents again.

Robbed of a proper goodbye, they would not see him marry.

They would never meet his sons, his grandchildren, and they would never grow old.

I was heartbroken for his loss.

(sorrowful music) The acres upon acres of barracks, reduced now to piles of bricks, stretch out as far as the eye can see.

Looking out over them, it is impossible to deny the Nazis' cruel intent.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was made for the systematic murder of over a million human beings.

It was a killing factory.

The last time Vladimir had seen these buildings, he had been a young man of 19.

He looked out over them now with the wisdom of a 94-year-old man.

"How can one person do that to another person?"

he asked.

(striking poignant music) It was here that his desperate loneliness had turned to hatred and thoughts of revenge.

He refused to use the wheelchair.

He was gaining strength with each step, fueled by those raw emotions he had felt as a young man.

As we walked toward the women's barracks that was used to house the very ill before being sent to their death, I could tell Vladimir was struggling with the heaviness of this place.

The brick and wooden barracks were barely fit to house animals.

Many originally had dirt floors and were meant to house from 400 to 700 prisoners.

Sanitary conditions were abysmal.

Lice and rodents were prevalent, and dysentery, tuberculosis, and typhoid were rampant among those in such close quarters.

Prisoners were not permitted to use the toilets at night.

These inhumane conditions contributed to a steady decline in the health of the prisoners, often resulting in death.

Once we were inside the barracks, the memories that came over him were almost too much to bear.

- [Vladimir] This were the beds on both sides.

But these were the barracks you lived.

And you (indistinct).

You don't too much to be alive.

You didn't need toothpaste and toothbrush.

You didn't need paper to clean your... You were permitted to go once in the morning to the latrines.

You didn't need spoon to eat.

You got soup in the dish.

You drank it with your fingers to get everything that was solid.

They really just dehumanized you to put you on the level of an animal.

(soft, somber music) And you were so cold.

When I was lying in the bed, I was shivering, shivering, shivering.

When I was in the infirmary, they were just something like this there.

I always had to share the bed with another guy who died during the night.

The morning, they pulled him out, put another in.

(soft, somber music continues) This is the end of Birkenau.

- Here, can you manage to step?

- I'll jump.

- No, don't jump, not today.

Tomorrow we jump.

- [Julie] Tomorrow we jump.

- [Vladimir] Okay, thanks.

- We looked over the remains of two of the crematoriums, crema two and crema three, and the site where the two largest gas chambers had once stood.

They were destroyed at the end of November 1944 by order of Heinrich Himmler.

They had continued to work day and night for six weeks after Vladimir's arrival.

Now a pile of crumpled metal and brick, they were no less menacing than if they had still been standing in perfect condition.

The train tracks nearby were put down late in the war to bring the Jews into the camp closer to the gas chambers.

Those selected for death walked straight to the gas chambers, while those selected to work and die later walked down the road where they were disinfected, given clothes, and put to work.

The international monument was erected in 1967, a Cold-War-esque sculpture consisting of dark monoliths.

It is situated close to the crematorium remains.

Granite plaques inscribed in every European language, Yiddish, and English are on display just feet away from where the Jews were gassed.

We walked slowly past the rows of plaques written in French, Greek, Hebrew, Croatian, Italian, Yiddish, and Russian until we found the one in Czech.

- This is Czech.

- This is Czech?

- Mm-hm.

- Forever let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity, where the Nazis murdered about 1 1/2 million men, women, and children, mainly Jews from various countries of Europe, Auschwitz-Birkenau 1940 to 1945.

(soft, somber music continues) Does being here after 75 years, is it what you imagined, or is it different than what you've been thinking about all these years when you sort of pictured it in your mind?

- It's not.

It's not so real as it was 75 years ago because it's empty.

When we came here, it was full, these barracks on both sides.

Though the feeling is the same as it was the first time.

It must be very depressing for you too, right?

When you look around it, it's unreal.

Look at it.

- It is unreal.

- Huh?

- It is unreal.

- It's unreal.

Yeah, for me, I would say it's a certain closure because I can't do anything more for all the dead.

They were my relatives, but at least I did this, that I came back at the end of my own life to see where their life ended.

It's really like going to the cemetery to say goodbye.

(haunting music) (female vocalist singing) (Julie exhales) (Julie cries) - [Julie] There was nothing left to say.

Vladimir would tell us later, "I am so glad I went."

The scope of the genocide is impossible to comprehend, and for the survivors, impossible to bear.

The Pinkas Synagogue in Prague bears the names of all the Czech Jews who were murdered during the Holocaust.

The names of Vladimir's parents, Karel and Hermina Munk, are written on its walls along with 78,000 others.

It would take 78 buildings like this one to list the names of all six million victims.

- Why me?

Why not the other?

It was plain luck.

I didn't do anything on arrival.

The truth is, and I don't talk about it, that I did some dishonorable things.

And most of the survivors did them, because to survive, you were not a nice person.

Anne Frank was a nice person.

She didn't survive.

I had to steal.

I have to lie.

I have to cover.

I had to do all kinds of things to survive, but they were not all honorable.

But it's important for the new generation to realize that something bad, it just happened in the 20th century, and that it was caused by most industrialized and most intelligent nation in the world.

Germany was on the top of everything.

It means that it can happen again.

It doesn't have to be in Germany.

It doesn't have to be in Europe, but it can happen.

(upbeat string music) - We traveled to Poland at the very beginning stages of the pandemic, and no one knew what was around the corner.

We were flying.

We were literally in rooms with thousands and thousands of people from countries all over the world.

And we made it home safely.

We celebrated Vladimir's 95th birthday at the end of February.

And within weeks, the whole world was on lockdown.

This was going to have a real impact on him.

At a certain point during the pandemic, it became very clear that Vladimir was having some serious health problems.

His cardiologist recommended that he get a valve replacement, which would seem crazy for most people to be even considering at the age of 95.

But his doctor felt that he was a good candidate.

He saw how active Vladimir was and how much he embraced life and what kind of shape he was in.

And he confidently suggested to him that he get the surgery, not the kind of thing you wanna do during the middle of a pandemic.

But it wasn't really elective surgery at that point.

- [Man] Morning, Vladimir!

- [Vladimir] The last minute of my life.

- Oh, stop.

(Vladimir and Julie laugh) - They said, "You have the problem with the heart only."

So I said, "Sign me for it."

Then they asked me, "Do you have any questions?"

I said, "Yeah, can you drink wine after the operation?"

And they looked at each other.

There were four doctor, said, "We better start fast."

- [Julie] Vladimir came through the surgery with flying colors.

- [Vladimir] Everything was great.

It lasted for about six weeks.

Then I started to have shortness of breath, such shortness of breath that I had to call the ambulance.

- [Julie] Vladimir was suffering from congestive heart failure.

From that moment forward, he would have to maintain a delicate balance of fluids to protect his heart and his kidneys.

- I found out even an improvement.

Instead of water, I drink beer.

You don't need so much beer to just cool your cells because it's bitter.

It's cold.

It helps.

So maybe in the future, we can make a patent for the breweries that they'll make a special beer to protect you (laughs) after heart operation.

- [Julie] Vladimir made the best of what he could and celebrated his 96th birthday on Zoom with his sons, their wives, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

As lockdown continued after Vladimir had the surgery, he was very frustrated.

He was asking, "Why did I get the surgery?

Because I'm still in lockdown, so I can't enjoy life."

And he was actually getting pretty depressed.

And then the minute they started talking about the vaccine, everything changed.

I don't think the irony was lost on any of us that as he rolled up his sleeve to offer up his arm for the second vaccine that his tattoo was clearly evident, the tattoo that he had received at Auschwitz.

And now in that same arm, he was getting the second dose of a life-saving vaccine that was going to open up his life and give him freedom to enjoy the rest of his life.

- [Woman] Yay, yay, yay.

- It has really been a full life that he has lived, and it's terrific to still have him around at this age.

And I'm at a point where I think that I should be putting him in my will because he's likely to outlive me.

(man and woman laugh) - Even being survivor, look how many times I lost everything that I worked for or I made and started over again.

As a child from the high school to concentration camp, return without parents, without anything.

Went to school, finished school, graduated, got finally PhD, worked in the research, was successful, got state prize which was the highest award in Czechoslovakia.

I had to leave everything there, move to the United States without any money.

Started again with no money, no nothing.

Finally, I was very careful not to do anything that I will lose my job or something like this.

I retired, and, well, how much can I lose now?

So, now I am waiting for the end, but it's a comfortable waiting, you know?

(haunting upbeat music) (female vocalist singing) Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk was made possible in part by the generous support of the following people.

Return to Auschwitz: The Survival of Vladimir Munk is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television