Hemingway, the Sea and Cuba

Special | 1h 1m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

Q&A with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Cristina Garcia, Brin-Jonathan Butler and Ann Bocock.

In this virtual event series, filmmakers and special guests explore the writer’s art and legacy. Conversations on Hemingway: Hemingway, the Sea and Cuba was presented by South Florida PBS, The Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum, and FIU Casa Cuba. It features Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Cristina Garcia, Brin-Jonathan Butler and Ann Bocock.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for HEMINGWAY was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Annenberg Foundation, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, and by ‘The Better Angels Society,’ and...

Hemingway, the Sea and Cuba

Special | 1h 1m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

In this virtual event series, filmmakers and special guests explore the writer’s art and legacy. Conversations on Hemingway: Hemingway, the Sea and Cuba was presented by South Florida PBS, The Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum, and FIU Casa Cuba. It features Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Cristina Garcia, Brin-Jonathan Butler and Ann Bocock.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Hemingway

Hemingway is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Conversations on Hemingway

Join the filmmakers and special guests as they explore the writer’s art and legacy. The hour-long discussions feature clips from the three-part series.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Conversations on Hemingway has filmmakers and special guests explore the Hemingway's art and legacy in hour-long discussions, featuring clips from the three-part documentary series.

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Joyce Carol Oates, Francine Prose and Edward Mendelson. (1h 4m 12s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A event with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Amanda Vaill, Howard Bryant and Paul Elie. (1h 4m 44s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A event with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Tobias Wolff, Abraham Verghese and Alan Price. (1h 7m 21s)

Hemingway, Gender and Identity

Video has Closed Captions

A virtual Q&A event with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Mary Karr, Marc Dudley and Lisa Kennedy. (1h 8m 38s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A event with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Lesley Blume, Patt Morrison and Rachel Kushner. (1h 4m 7s)

Hemingway and the Natural World

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Sarah Botstein, Terry Tempest Williams and Jenny Emery Davidson. (1h 4m 31s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Virtual Q&A event with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Alex Vernon and Melinda Henneberger. (1h 4m 28s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Virtual Q&A event with Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, Verna Kale, Tim O’Brien and Paris Schutz. (1h 4m 9s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Good evening everyone, and thank you for joining us.

I'm Dolores Sukhdeo, President and CEO for South Florida PBS, and I am delighted to welcome you tonight to the South Florida conversation, Hemingway, the Sea and Cuba.

We are thrilled to be one of only nine stations across the nation selected to host one of these fascinating conversations, ahead of the April 5th premiere of Ken Burns' and Lynn Novick's newest documentary, Hemingway, airing on South Florida PBS, as well as on every PBS station in the country.

South Florida has a special connection to Hemingway.

Not only did Hemingway choose Key West, also known as Cayo Hueso as his home, but he also visited Cuba on a regular basis.

And these visits and his love of the sea were the inspiration for his Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Old Man and the Sea.

Participating in tonight's discussion, are filmmakers and great friends of South Florida PBS, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, writer Cristina Garcia, and author and journalist, Brin-Jonathan Butler.

The conversation will be moderated by Ann Bocock, host of our local book review program, and podcast, Between the Covers.

The three part Hemingway documentary will premiere on South Florida PBS's WPBT, on Monday April 5th through Wednesday April 7th at 10:00 PM, and on WXEL Thursdays, April 8th, 15th and 22nd at 9:00 PM.

Thanks to all of you for your steadfast support and for joining the conversation this evening.

Now, before we start the discussion, enjoy a sneak preview of Hemingway.

(gentle music) - Hemingway was a writer who happened to be American, but his palette was incredibly wide, and delicious, and violent, and brutal, and ugly.

All of those things.

It's something every culture can basically understand.

Every culture can understand falling in love with someone.

The loss of that person, of how great a meal tastes, how extraordinary this journey is.

That is not nationalistic, it's human.

And I think with all of his flaws, with all the difficulties, his personal life, whatever, he seemed to understand human beings.

- [Man] You see, I'm trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across, not to just depict life or criticize it, but to actually make it alive, so that when you have read something by me, you actually experience the thing.

You can't do this without putting in the bad and the ugly, as well as what is beautiful.

Because if it is all beautiful, you can't believe in it.

Things aren't that way.

It is only by showing both sides, three dimensions, and if possible four, that you can write the way I want to.

(bright music) - [Narrator] Ernest Hemingway remade American literature.

He paired storytelling to its essentials.

Changed the way characters speak, expanded the worlds a writer could legitimately explore, and left an indelible record of how men and women lived during his lifetime.

Generations of writers would find their work measured against his.

Some followed the path he'd blazed.

Others rebelled against it.

None could escape it.

He made himself the most celebrated American writer since Mark Twain, read and revered around the world.

- It's hard to imagine a writer today who hasn't been in some way influenced by him.

It's like he changed all the furniture in the room, right?

And we all have to sit in it to some, you know, we can kind of sit on the edge of the arm chair on the arm, or do this, but you know, he changed the furniture in the room.

The value of the American declarative sentence, right?

The way you build a house brick by brick, out of those.

Within a few sentences of reading a Hemingway story, you are not in any confusion as to who had written it.

- I can't imagine how it's possible that any one writer could have so changed the language.

People have been copying him for nearly a hundred years, and they haven't succeeded in equaling what he did.

- If you're a writer, you can't escape Hemingway.

He's so damn popular that you can't begin to write till you try and kill his ghost in you, or embrace it.

And I think, I identify that most about Hemingway, that he was always questing.

The perfect line had not happened yet.

It was always a struggle trying to get it right, and you never will.

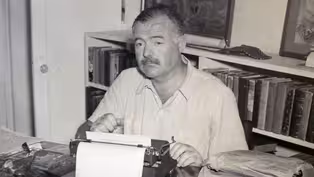

- [Narrator] For three decades, people who had not read a word he'd written thought they knew him.

Wounded veteran and battlefield correspondent, big game hunter and deep sea fisherman, bullfight aficionado, brawler and lover, and man about town.

But behind the public figure, was a troubled and conflicted man who belonged to a troubled and conflicted family, with its own drama and darkness and closely held secrets.

The world saw him as a man's man, but all his life he would privately be intrigued by the blurred lines between male and female, men and women.

There were so many sides to him, the first of his four wives remembered, that he defied geometry.

- He was open to life.

He was open to tragedy.

He was open to feeling.

I liked that he fell in love, and he fell in love quite a few times.

He always had the next woman before he left the existing.

- [Narrator] He was often kind and generous to those in need of help.

And sometimes just as cruel and vengeful to those who had helped him.

- [Man] I have always had the illusion, it was more important or as important to be a good man as to be a great writer.

I may turn out to be neither, but would like to be both.

- [Narrator] Hemingway's story is a tale older even than the written word, of a young man whose ambition and imagination, energy and enormous gifts, bring him wealth and fame beyond imagining.

Who destroys himself, trying to remain true to the character he has invented.

- One of his weaknesses, I was going to say failures, and this was a great pity, it's a great pity for any writer, he loved an audience.

He loved an audience and in front of an audience, he lost the best part of himself, by trying to impress the audience.

- I hate the myth of Hemingway, and the reason I hate the myth of Hemingway, it obscures the man, and the man is much more interesting than the myth.

I think he was a terrific father, sometimes.

I think that he was a loving husband, sometimes.

I think he was like so many people, except this enormous talent.

Hemingway is complicated.

He's very complicated.

- [Man] The great thing is to last, and get your work done, and see and hear, and learn and understand.

And write when there is something that you know, and not before and not too damned much after.

(solemn music) - Good evening, I'm Ann Bocock, host of Between the Covers, produced by South Florida PBS, and I want to welcome our viewers to this special conversation, on Hemingway, the Sea and Cuba.

And this is ahead of the upcoming three part documentary series, Hemingway, beginning on April 5th.

On the panel this evening, are award-winning filmmakers, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

And they're joined by the very talented writers, Cristina Garcia and Brin-Jonathan Butler.

We'd love for you, the viewers to take part.

So please drop your questions in the chat.

We will get to those a little later in the hour.

And we have viewers not only from all over the country, from all over the world, and they've been very loyal through, this is number five of the series of conversations and there will be a total of nine.

Ken, I'd love to start with you.

If perhaps there is a positive note during this year of staying home and quarantined, perhaps it's that reading has seen a resurgence, and not just reading but rereading.

Reading books that we read from our past.

And I know that timing is totally coincidental.

This documentary had to be in the works for years, decades.

So I want to know if you have re-read, if you were doing it while you were making the film, and did going to the places, did going to Key West, did going to Cuba give you a new appreciation for Hemingway?

- Well, that's a really complicated question.

I'll say one thing, that we obviously, making this film over the last six years, all of us involved have come back and revisited the works that first got us interested in Hemingway, as early as high school for me and beyond.

I know that's the same for Lynn and that the production afforded us a chance to see this material in a new light and do that wonderful thing, which is to have a piece of fiction, or in the case of Hemingway, also non-fiction, either a novel or a short story or some of his great works of non-fiction, to be able to rearrange your molecules in a new way.

I'd like to say about the last year, we've been way too busy to be able to have any kind of recreational anything, but I'll tell you that one of the reasons why we're busy is that we still have the great privilege to work, and to work on a number of projects, and particularly over the last year, to spend a good deal of that time finishing this film and getting it to the point where we'll be able to share it next month, on the 5th, 6th, and 7th of April nationally.

And it's our network that deserves the credit here.

You know, PBS knew exactly what to do, the second this thing hit.

When we shut down, they began putting out Lynn in my baseball series, you know?

Baseball was canceled and it wasn't sure that it was gonna start up.

And so that is, they began to work with parents and teachers and students to figure out how to enhance the difficult task of being online.

So I think that at the heart of our network, has always been a love of books and a love of reading, and the sort of the seriousness with which we take our subjects, all sends people back to books.

I mean, one of my most favorite calls I've ever received in my life was from Shelby Foote, who after the series was out and his series, which had sold respectively of three volumes, he called me up and he says, "Ken, you made me a millionaire."

And that was because the book sales went up, and I'm looking forward to a spike in sales for a guy who's been gone for an awfully long time.

And that's exciting to us.

But Lynn can talk a little bit about the places become hugely, hugely important for Hemingway, which is why we're here in South Florida to talk about things.

But Lynn had the opportunity to visit both Key West and Cuba, so given the geographical proximity to you all, let Lynn do the back half of your question.

- Okay.

- I think I will.

And I will say Ken is in New Hampshire, am I correct?

- I'm in my barn in New Hampshire, which Lynn often stays in when she's visiting, but nobody's been here for a year.

And down below, we have a room where we have screenings with our consultants and in the case of Hemingway, we'd have loved to have, we did have before COVID some in-person stuff, but to have people up looking at the film itself and being able to talk about it, and then there's an editing house a mile and a half away that we actually work, but it's been empty except for one person.

We're a little, the tumbleweeds are going through here.

And it's just me and my dog who's around here someplace.

And, but we're connected by this magnificent thing called Zoom, daily, weekly, monthly, and now we've passed the year, we've lapped ourselves.

- Well, what a wonderful thing to have this Zoom, because there are people from all around the world that can take part.

- Just think, when we come and visit you guys, we cram into an auditorium.

- Right.

- We share clips, and we have a Q&A, and it's wonderful, but now we've really exploded it.

And so we're always surprised that in each of our regional things, Chicago and Kansas City and LA and Idaho, that we were suddenly getting people from all around the country.

And Ann, as you said, around the world.

- Lynn, I'm gonna let you take the second part of that question.

- Okay.

- And you know, I'm going to admit, I'm in South Florida, I've been to Key West so many times.

I love the Hemingway House, and I can feel his presence in that house.

That said, I've never been to Cuba.

So I'm probably the only person in this whole Zoom thing here that has not been to Cuba.

So that's part of my question.

How did, what did it feel like putting this project together but also being in that environment?

- Yeah.

Well, my visit to Key West, which was, I think 25 years ago, and my visit to Hemingway House is kind of what put me personally on this journey of just feeling his presence, like you said, in the room where he worked and seeing his, the objects he owned and thinking about the time he spent there, what that place meant to him and just, you know, then reading voraciously, a lot of his work and work's about him then.

And, you know, having, I guess an image in my head of the home in Cuba, the Finca Vigia, I've heard so much about it.

Everyone who goes to Cuba that I know has been there, and it is a place to see.

But I couldn't quite, and I'd seen pictures, but going there was different.

Our associate producer, Vanessa Gonzalez-Block and I were able to make two trips to Cuba, one to go and kind of scope it out, meet a Cuban producer who would help us do a filming there, and meet the people who are in charge of the home.

And we were helped in that with the Finca Vigia Foundation, which is based in Boston, which has dedicated itself to restoring and preserving the home and all the objects in it, which is an incredible national/international treasure.

So, you know, we can talk about it a little bit more later, but feeling his spirit in Key West is one thing.

But the home in Cuba, he lived there for 20 years.

And when he left, he didn't know that he wasn't coming back.

So everything he owned was in that house.

That was his only residence at the time.

I mean, he had the house in Idaho, but that's where everything he owned was.

So when you walk in there, you see everything that belonged to him, his records, his eyeglasses, his, you know, his razor, his shoes, all the animals that he killed that are mounted on the wall, his books, and there're books everywhere, every magazine.

I mean, he saved everything.

So it's quite an extraordinary, I don't even know what the word is, not a shrine, it's not a museum, it's his house.

And it's his place.

- And you know, one thing I'll say, and we did benefit from the help of the Finca Vigia Foundation and its head, Mary-Jo Adams.

But one of the things that's incredibly critical, and this is an appeal to the PBS family, is that the foundation really needs support.

There's some structural issues there now, there's termite damage, there's water damage.

And it really behooves us if we care about it, and not just pay lip service, to make sure that that ability to go in as Lynn did, and look at the bottles of liquor, you know, half drunk, the records on the record player, the little notations of his weight by the scale in the bathroom, all of those things have to be there because, you know, we are interested in listening to the ghosts and echoes of this inexpressibly wise past.

And part of that is our own individual, but also collective commitment to the preservation of these sites.

And this is one that's central, to understand Hemingway is to, of necessity, get there or see it in some way, shape or form, and feel his presence in every room.

- And that's, this was the home that he spent more time in than anywhere else that he ever lived.

- That's right, ever.

- Yes.

- Yep.

- Absolutely.

- Cristina, I've got to get you into this, because I really want the author's take on the clip we just saw.

Tobias Wolff said he couldn't imagine a writer who hasn't in some way been influenced by Hemingway.

You've written seven novels if I counted correctly, you were a finalist for the National Book Award for your book Dreaming in Cuban.

So how do you feel a Hemingway influence?

- I feel that he was absolutely seminal to my becoming a writer.

It's funny, we were talking about rereading, and I re-read A Moveable Feast among other, I mean, even before I knew I was gonna be participating in this, and I first read it at 22.

So 40 years later, I read the same book.

And what was astonishing to me was that, well, first that it's the prose handbook equivalent to Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet.

It's that important.

And so not only does it hold up the bookends of a writing life, but I realized 40 years later how much I had absorbed, internalized, and even interjected is not too strong a word.

Like just how to live and put the language down, how to make it, how to invite the entire world in to your novel.

And for that, I will always be grateful.

And he was, he had a big debt to the Russians.

I always loved the Russians and his whole notion of family as a dangerous, you know, families as dangerous echoes, that wonderful opening to Anna Karenina about families.

Basically he invited us all to become writers, via the virtues of his experiences and struggles.

- Wow, well said, well said.

- That is well said, thank you, Cristina, I didn't ask where you are physically now.

- Oh, I'm in Northern California, although I have a little palm tree for tropical effect.

(laughing) - Brin, I want you to pick up on that thread, because literally you followed in Hemingway's footsteps.

You wrote The Domino Diaries, My Decade Boxing With Olympic Champions and Chasing Hemingway's Ghost in the Last Days of Castro's Cuba.

So I'm gonna let you take it from here, if you would pick up that thread.

- Yeah, the subtitles are the publisher's doing.

It's a mouthful.

(laughing) Yeah, like Cristina was saying, I was so moved the first time I read The Old Man and the Sea.

And to know that an American had been so honored and cherished in a country like Cuba that's so representational by its opposition to America.

I thought, "What is going on here?"

And you arrive and you have this incredible museum of, it seems as if he just left the place.

Incredibly haunting to visit it.

I was 20 years old.

And you had, at that time, the accessibility to Gregorio Fuentes who actually was the basis for The Old Man and the Sea.

I was able to talk to him for $15.

And there he is at 103 years old.

So Cuba was sort of everything I imagined it would be, based on that novel.

Of course it's so famously frozen in time in some ways, but also in a lot of ways that are incredibly beautiful.

You're warned about the poverty that you're gonna encounter before you go there.

And what's left out, is it reminds you of the poverty that you have, where you come from, because you see so many riches that are not measured in money, but the sense of community, the sense of family, these were things that were kind of resonant from this little book that he wrote.

And after he finished it, his wife read the manuscript and said, "I forgive you for everything."

And there was a lot to be forgiven for.

And I love that Hemingway reminds us that people are never remembered for what they have.

They're remembered for what they give.

And then you can carry Hemingway books around the world and people will come up to you and say how much these books meant to them.

And we're 60 years away from his death, now.

He's been dead as long as he was alive.

And still people are finding tremendous connection to the themes of his work.

And it's a profound legacy that I can't think of an author in literary history who inspired more tourism or pilgrimages, which suggests that people are still connecting to who he was.

There's a timelessness to him that is still deeply resonant.

- I can't even imagine at 20 years old, what you did, this is absolutely incredible.

And we will get to more of that.

Lynn, I know he had four wives.

He was always in love with someone.

Personally, I think he loved his boat maybe as much as the wives, because he had the boat for longer than I think any of them.

There is a clip coming up now, if you could tell me what that is.

- Yes, exactly.

He did have a custom made boat, which was a very beautiful and fancy boat for the time.

And what he loved was deep sea fishing.

And we have a scene to show of just his relationship to the sea and being out on the boat.

And I think it was a sense of isolation.

You know, he lived so much because by this time, where we're talking about the early thirties, he was very, very, very famous already.

And this is a place he could get away.

So, here's a clip about Hemingway and the sea.

(lively music) - [Man] The Gulf Stream and the other great ocean currents are the last wild country there is left.

Once you're out of sight of land and of the other boats, you are more alone than you could ever be hunting.

And the sea is the same as it has been since before men ever went on it in boats.

No one knows what fish live in it, or how great size they reach or what age.

When you're drifting out of sight of land, fishing four lines, 60, 80, 100 and 150 fathoms down in water that is 700 fathoms deep, you never know what may take the small tuna that you use for bait.

And every time the line starts to run off the reel, slowly first, then with a scream of the click as the rod bends, then you feel it double, and a huge weight of the friction of the line rushing through that depth of water while you pump and reel, pump and reel, pump and reel.

Trying to get the belly out of the line before the fish jumps.

There is always a thrill that needs no danger to make it real.

- [Narrator] Hemingway had a 38 foot fishing boat custom built for himself.

"A sturdy boat," he wrote, "Sweet in any kind of sea."

He named her Pilar, one of his nicknames for Pauline.

And he spent weeks sailing the waters off Key West and the Gulf Stream off Cuba and around Bimini in The Bahamas in search of good times and giant fish.

(bright music) - That was sheer happiness for him.

I've always thought that seeing the fish come, is like seeing a huge elephant or a tiger that may emerge from the sea.

You don't have any warning, they're just suddenly there, you know, and that I think was a thrill that he never got enough of.

(lively music) - Ken, I have to ask, that so much of what I thought I knew about Hemingway turns out to be a myth, as is explored in the film, but there was this sort of love/hate relationship with fame.

And I'm wondering, was being at sea, was being in Key West and in Cuba, was he running from it or did, was this a refuge for him?

- It's such a mix and a melange, you know.

I think we feel the same way.

And as we approach a subject, we come armed with whatever conventional wisdom or baggage that we have.

We're not there to tell you what we know.

We're rather there to share with you at the end of a long, in this case, multi-year process, our process of discovery.

Look what we've discovered and all of it is, I had no idea.

And that's part of, I think, what we like in our films is not going in knowing, but going in unknowing and the discovery of it.

This is a man who is fed by solitude, who's fed by nature and nurtured at the earliest part of his life.

He needs that, it is sustaining for him.

And yet he is also a social creature, gregarious, and he goes into the world, into the Paris of the 1920s, into the reporting all around Europe, into wars, all of that's there.

And then he's also at the same time mythologizing, he's creating his own mystique in a way that in the United States, only in the previous century had Mark Twain done that kind of thing, but he did it on this, in some ways, an even grander scale.

And a lot of it was true.

He was a deep sea fishermen, as you can tell.

He was a big game hunter.

He was brawler.

He was a, you know, a man about town, a bon vivant.

You know, he could get, he could fish in upper- All of those things were true, but somehow he built this elaborate sort of PR campaign about it for himself, that then became a kind of prison.

And it was always, you could see him, and just as Cristina was saying, you know, echoing the opening of Anna Karenina, he's also desperate for family but he's desperate to get away from family.

So he needs to strike out.

And I think that in Key West and in Cuba is his search for another kind of nature, that solitude, where you're away from land and you're in this primordial space.

And you feel the thing that Hemingway was always getting after, the tenuousness of life.

And because he's got this reputation that he's also trying to mask his own curiosities, his own appetites, his own vulnerabilities, his own insecurities.

And then of course, as the demons begin to catch up, of mental illness, of severe head traumas, of alcohol, of depression, dementia, all of the things that are sort of chasing him down, you know, he's running faster and faster, but somewhere out in these places, as his son, Patrick said, something happens that's magical for him.

And there's an intimacy even with the unforgiving.

And he's not a romantic about nature, this unforgiving and open landscape of the sea.

It's sustaining.

And, but boy, it's complicated.

You can never say when the image leaves off and when the real person begins, except in the writing, you know?

The writing is what he left us.

And it's just, it is, as everyone has described here, Brin and Cristina and Lynn, it's just so spectacular.

And now that we know a lot of what the facade was trying to protect, gender fluidity and curiosity about androgyny and the other sex and all of that, he then sort of reinvents himself for us, as you know, 60 years of, as Brin said, after his death.

He's now, he's got fresh new ways of speaking to us, or we can understand him, without being scandalized by things that 60 years ago, or 80 years ago would have been you know, impossible to talk about.

Gertrude Stein, no conservative slouch, read his story up in Michigan and said, "This is obscene.

"It cannot be published again."

And it, in fact does not appear in the second volume of In Our Time.

And you know, this is Gertrude Stein, about a guy who's writing about the intimacies of a date in Michigan.

And it's still about as powerful as you could get, as if it was written, you know, appeared in The New Yorker this week.

- You know, Lynn, I knew when I first heard you were putting this documentary together, I knew I was going to be captivated.

But I came with it with what I thought Hemingway was.

And you've really opened my eyes on that.

I want to know is as you were putting this project together, did you evolve in your feelings?

- Yes, absolutely.

I mean, I just speak for myself, but I think it's probably true for everybody.

And like Ken was saying, we start off, you know, we know enough to know this is gonna be a worthwhile project to undertake, but we're by no means experts.

And we actually surround ourselves with experts, people who've studied Hemingway and can help us really you know, sort of see the forest for the trees of what's important to say.

That being said, you know, I think even seeing the photographs gives you a different sense of a person than reading the words on the page, seeing the letters that he wrote to his family, to his wives, to his parents at different stages of his life, some of them beautiful and warm and loving, some of them cruel, some of them funny, sad.

I mean, every emotion you can imagine are expressed in those letters, which are such a treasure trove and gave us such incredible access to his inner life and his relationships.

And then spending time with his work and trying to figure out, okay, we're gonna do The Old Man and the Sea.

What passage are we gonna have Jeff Daniels read for us?

You got read the whole of The Old Man and the Sea, and pick the two passages that really are gonna crystallize that book.

And, you know, for every work of his, we had to do that.

So that was a daunting, but also wonderful, just to be able to go back and think, okay, what can we pull out that's gonna be the essence of these works?

And so through all of that, I think I gained a deeper appreciation for his talent, his sophistication as an artist, his dedication and also a deeper understanding for his complexities as a human being.

Because, you know, there are lots of aspects of his personality, of his behavior and his life story that are hard to deal with.

So sort of having to carry all of that, you know, I emerged with a much fuller understanding of him than I had to begin with.

- I think that complex doesn't even begin to (laughing).

- No.

- No.

- We looked for words, exactly.

We've been saying- - We'd bring it out.

- This is not good enough.

- We'd bring it out.

- We need a better word.

Hemingway could help us come up with a better word.

- Or not.

- Or not.

- Or a shorter word.

- Yeah.

- Yeah.

- You know, Brin-Jonathan, I'm curious.

The mythology of Hemingway is so fascinating.

Certainly the picture of this man's man, the game hunter, a boxer, a drinker, the deep sea fisherman.

All of this was pretty much etched in stone by the time he got to Cuba.

He ended up giving his Nobel Prize to Cuba.

I want you to weigh in on this if you can, from your time there.

Do you have a feeling of what he meant to the Cuban people?

Do you have a feeling of what the Cuban people thought of him?

- Yeah, I mean, I think Gertrude Stein, when she wrote about him in the autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, tried to slight him by saying he had passionately interested, rather than interesting eyes.

And I would say that's what I was blown away as a misconception about Hemingway, is he's a much more interested person than he is even interesting.

And so in approaching Cuba, he approached it not in the classic, ugly American kind of manner, but looked for correctives to the culture that he came from from Cuba.

And so I think their way of life, their values, the cultural richness of Cuba was something.

He declared himself a Cuban at a certain point.

So I think the macho-ness, yes, those sides are there to him.

But as you were talking about up in Michigan, it's not just a story of a date.

It's a story of a date rape, told from the perspective of a woman being raped.

Hills Like White Elephants is the story of a man pressuring a woman into an abortion.

So you're seeing him confronting toxic masculinity.

As much as he demonstrates it in other areas, he's taking huge artistic risks to approach the perspective of women.

Farewell to Arms, we have childbirth leading to the death of the mother and the child.

So there's a sensitivity to him and there's so many contradictions to him.

Well, what is a more complicated place, or a place of contradiction than Cuba?

(chuckles) You know?

So I think Hemingway fit in very well there, as an artist who had all of these different faces.

Capote he said he was a closet everything.

I think Cubans would argue, he wore many masks, but he was those masks, as much as he was trying to hide from things.

He's just such an immensely complex kaleidoscopic person.

- That's so interesting.

Cristina, there's something about the sea and, you know, on a basic level, it can be soothing and calming.

And then in a moment it can be deadly and perilous.

You yourself have written about the sea, and here is Hemingway writing as an American living in Cuba.

I'm curious from, and I'm really you know, putting you on the spot here, but what do you think the sea itself represents for the Cuban people?

How did Hemingway look at it from that perspective?

- A couple of things come to mind.

Obviously Cuba is an island.

And so pretty much your horizon is always that blue.

It's always that sea with all of its attentive complexities, and also the promise of solitude.

And I'd like to connect it back a little bit, 'cause I was thinking about earlier, when you were talking about that yearning for solitude, how, and if it's connected to the art of omission in his work.

Because so much of his omission is what is the greatest strength of his work.

And I think so much of his solitude, which is a form of social omission in a way, also served to strengthen himself, strengthen his resolve, to satiate his own hunger for memory and a sense of self.

And so I think the sea serves many purposes.

Its mystery, its power, its potential for solitude, its proximity to death, and ever the sustaining blue of the horizon.

- And I would, I mean, I think this is so interesting.

You know, we, in making the film, we engaged this, but in thinking about it in this conversation, there's also the contest with the fish, which you know, I mean, I didn't really understand until I saw the images that we just showed how big those fish are, and how unbelievably difficult it is to land them.

And it could take six hours, eight hours, and you would be completely depleted.

It was like running a marathon, and not that many people could actually do it.

And how he sort of decided to master this thing and take on these unseen, you know, monsters of the deep, there's something very primal about that.

There's not that many opportunities in modern life to do something like that.

So you have to go out on the ocean to find those fish and to do battle with them.

And that seems to be, he did it for his own sake because he wanted to, but then he also found incredible inspiration from the existential questions that that raised for him.

So, I'm not sure he went out there specifically knowing he's going to write a great book about it.

He went out there because he wanted to do it, but then it worked on him, you know?

I find that really interesting.

- I'm just gonna toss this out to to the panel, and it really has to do with his time in Cuba, his political awareness, if it existed, of being an American in Cuba.

Did he feel a responsibility, and I'm gonna ask the writers, I think, did he feel a responsibility in how he had to write?

- In relation to Cuba?

- Yes.

- Well, I mean, this is a guy, For Whom the Bell Tolls let's remember in 2008, when Obama was running against John McCain, both of them cited the same literary hero, which was Robert Jordan.

Simultaneously, Fidel Castro was using For Whom the Bell Tolls as a blueprint for guerrilla warfare in the Sierra Maestra in Cuba.

So again, this is a very complex subject in terms of how different people from very different political allegiances can sort of convene and see what they want to see in the characters, the complex characters that he writes about.

- Cristina, did you want to follow up?

- I would also just add very much like, Jose Marti, whom everyone claims as his own, culturally, literarily and otherwise, I think Hemingway has that effect on people as well.

And I know he named his boat after Pauline, but Pilar is also a very famous poem by Jose Marti.

He couldn't have stumbled on a better name.

It's also my daughter's name.

But he also stumbled on an iconic name and image of Cuban literature.

So between his boat, Jose Marti, and his, it seems universal appeal.

And also I think he felt a responsibility to get it right, to make it right.

Not just describe what he saw, but to surrender and get fully involved in what he felt privileged to participate in.

And Cuba was one of those privileges for him.

- I do believe you have a character in one of your books named Pilar.

Am I correct?

- Yes, yes.

Pilar's everywhere.

The character came before the child.

(laughing) Multiplicities of Pilar.

- I still go back to he loved that boat as much as he loved his wives.

Lynn, I'm gonna toss it to you, because we have a final clip to watch.

So if you could set that up for us.

- Yeah, it doesn't need much introduction.

We're just going to show a scene that we dedicated to describing The Old Man and the Sea, which we've been speaking about already.

- [Narrator] The Old Man and the Sea, told a story of an old Cuban fisherman, alone in a skiff who hooked a great marlon that towed him far out to sea, before he could harpoon and lash it alongside.

But as he struggled to return to land, sharks devoured most of his prize.

Hemingway had originally planned to include the story as the coda to a longer novel, but he now wanted it to stand on its own.

"Publishing it now," he told Scribner's, "Will get rid of the school of criticism "that I am through as a writer.

"That claims I can write about nothing except myself "and my own experiences.

"It could even serve as an epilogue to all my writing "and what I have learned or tried to learn "while writing and trying to live."

Most readers seemed to agree.

The Old Man and the Sea appeared first in Life Magazine on September 1st, 1952 and sold well over 5 million copies.

The hard cover book when it was published would remain on the bestseller list for 26 weeks.

(speaking foreign language) - The Old Man and the Sea.

(speaking foreign language) - We now have questions from the audience, and boy, do they have good questions, so I am going to start with a question from Ed.

And Ed wants to know, "What was the allure of the Spanish culture "that actually intrigued Hemingway?"

Ken, would you like that one?

- Well, I think, you know, this is a developing relationship.

It starts with his trips out of France into Spain and being captured by that country's mysteries and its inscrutable national sport, and his kind of continue return to there.

And then of course, as he is participating as a journalist and collecting for the novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls in the Spanish civil war, that love is deepening, but the pain is also deepening.

And by this time he's beginning to escape to Cuba and escape the second wife, Pauline.

And so you're beginning to see the embrace of another Spanish culture.

If it can't be Spain itself, it can be Cuba.

And so I think there is a very legitimate love of it.

But he's a person, the reason why, you know, Lynn did an interview for our Vietnam series of the woman who as a teenage girl went down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to repair it, and took with her, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

It kept her alive, she felt.

And we interviewed for this film, John McCain, who was a person bombing North Vietnam, who felt that Robert Jordan is the key to him.

You know, Obama's connection is probably much less tenuous than John McCain who says, you know, to me, if you want to know who I am, it's Robert Jordan, period, you know?

Flawed man, flawed cause, trying to do his best.

So I think that a lot of him is built up in this culture and Cuba was a way to extend it.

It's an amazing relationship.

I mean, even Patrick, his son, said, he didn't really care for the Cuban people.

Like he was, this was a place of escape and yet he clearly cares of it.

And if you think about what happens in the thirties, he has the whiplash of all whiplashes.

He begins in a kind of almost libertarian anti-government mode.

And within a year, he is writing for the New Masses, a communist magazine, he is going to Spain to write about a Soviet controlled side of the struggle there with horrible atrocities, which he doesn't report until he gets to his novel, the novel being more truthful than the non-fiction.

And he also writes and narrates a film by a communist filmmaker, all within this sort of head whiplash giving short period of time.

I think it's so, so interesting.

- We have a question from Mary and it's to anyone.

"Do we owe Martha Gellhorn a thank you "for finding the house near Havana, "so that Hemingway got away from the bars "and the distractions in the city.

"Did he really get away?"

- Yes, that is very true.

They were living together actually in a hotel and they're both trying to work.

And he was, you know, very focused on his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and she was trying to do her own writing and they needed space.

And so she went out and found this rundown farm.

I mean, farm isn't really quite the right, it's sort of a manor house of a farm.

So it's not a farm house per se like we would think of a farmhouse.

It's a colonial style, beautiful home on the top of a hill, far from Havana and they rented it, and then they ended up buying it.

Then they ended up sort of doing work on the house and really making it their own.

And yes, it was far away from, you know, he could get away and he could get into Havana quickly and you could also get to the water quickly to get to his boat, which was very important to him.

- Nick and Barb from Windemere, Florida, are asking the panel, "We visited Cuba "and that's where he had his cats and his dogs."

Now, I'm just gonna do an aside.

If you visit the Hemingway house in Key West, his cats are there.

So you will see the descendants of those cats.

And they wanted to know if you could discuss how he thought his cats and dogs were a valuable aid in his writing.

- I don't think I have anyone- - I don't know.

I mean, I think they were companions and he loved them.

I'm not sure.

- Cat in the Rain, I could, we could send them to read Cat in the Rain.

- Right.

- And maybe think about what the meaning of that story is.

- I think that he's got enormous powers of observation, and particularly of the natural world, also obviously about human beings interact.

And I think what's interesting, even in Key West, he had a whole menagerie of pets there, and exotic pets too.

And it continues there.

And I think he's interested in being, and you know, our pets are a reminder that we're not the only beings.

And I think there's, there must've been some reason why he tolerated the proliferation of cats there, if not because they were like almost everything else in front of him, stuff, grist for his mill.

- And such a contradiction, this man who was a big game hunter, and you know, this macho man and he loved these little cats.

It's, you know?

We do have a question from Miriam, she's in Nashville.

"Did Hemingway play an active role "in supporting the Cuban revolution?"

We kind of didn't get there before, we were sort of on a tangent.

And I don't know, I'll leave that up to you.

- There's definitely letters where he talks about believing in his words, the necessity of the Cuban revolution.

But he did not really want to be actively political in Cuba.

He was really clear, if you're not willing to take up arms, you don't have a right to comment on the political landscape.

And of course, he's dead in 1961, so we don't know how he would have felt about where Castro and the revolution went.

- That's exactly right.

That's exactly right.

- As Ken said earlier, when he left, after, you know, after the Bay of Pigs in 1961, he really didn't think he was leaving forever.

This was- - No, and he didn't really want to leave, frankly.

I think that the U.S. government actually pressured him into leaving and said that if he stayed there, he'd be considered an enemy of the United States.

I think that's correct.

So, you know, we don't know whether he would have wanted to leave later, but he was not leaving under protest of Castro per se.

There was a lot of anti-American feeling at the time.

I'm sorry, Brin, yeah.

- Sorry, I was just gonna say, and Hoover had an extensive file on Hemingway, monitoring his movements, so his paranoia was quite justified on that front.

- All right, we're talking about paranoia.

We have a question from Laura, which is close.

She wants to know, "Was Hemingway ever diagnosed "as depressed or bipolar?"

- Oh boy.

- He was treated for mental illness at the Mayo Clinic, but we're not really sure about the diagnosis.

He was definitely having suicidal depression.

And I think that's as far as we can go with diagnosis per se.

So that's what he was treated for, among other things.

But there's certainly a history of mental illness in the family and mood disorders, so.

- And multiple concussions and probable PTSD from being 18 and being blown up, with 40 years of alcoholism compounding.

- And the self-medication that comes with that alcoholism.

There's not one thing, it's just, it's somebody riding as fast as they can ahead of a stampeding bunch of furies after him.

And who gets him, doesn't really matter.

He's gotten.

- Yeah.

- And there was the electric shock therapy too that he underwent, which, who knows really the short and medium, he didn't even have long-term effects.

It didn't, he wasn't around long enough.

But yeah, that too I'm sure contributed.

- Yeah, and having two plane crashes in two days doesn't help anyone.

We do have, we're gonna go to something a little more fun.

David is asking, "What were the bars in Cuba "that were his favorites?

"They seemed to be an important part of the experience.

"And are they still there?"

So Lynn, did you go?

- Well, the only one I'm really familiar with is very famous, which is called the Floriditas, and it's a real tourist attraction now, if you take a cruise ship to Cuba, you know, you basically have to go to Floriditas.

I'm not, I don't think it has the exact ambiance it had when Hemingway went there.

It's very, it really feels like you're on a Hollywood set of a bar from Cuba or something.

So I'm not sure.

I think you guys probably know better than we do where he actually, you know, other places he went.

- I love this question from Joan.

"She just started reading his letters "and he's come alive for me.

"Did he keep copies or were they collected from recipients?"

And so much of what you did was from letters and in my mind, is this, was it like a treasure trove or a Pandora's box?

(laughing) - Both, I, you know, what's great is that you have the literature and you try to form certain feelings.

You have the contours of biography done by the hard work of biographers, but the letters really fill things in.

So if, as we were speaking, you know, about some of the posthumous publications, Cristina was talking about A Moveable Feast, The Garden of Eden in which some of this gender fluidity is really, really out in the open.

And he knew it could not where he felt it should not be published in his lifetime.

There are contemporary letters that we were able to have that showed the same sort of thematic thinking that gives us a clue.

It's sort of an advanced notice.

So the triangulation that can take place with these letters, good and bad.

Let's remember there's some pretty God awful letters sent out about James Jones's From Here to Eternity, but also to his son.

And it's, one of his sons and it is hair curling.

- I do think that if you received a letter from Ernest Hemingway, you might save it.

- Yeah.

- There's a lot of people who have letters or had letters.

I mean, they didn't throw these things.

He saved copies, I believe there are a lot of letters.

He had, you know, secretarial assistance sometimes to type for him, or she typed and he had carbon copies.

But if he didn't, I think a lot of people saved those letters and there's been an incredible project to collect every single letter he ever wrote, and publish them in an ongoing volume of, I think they're gonna be 20 books, Cambridge University Press of every letter Hemingway ever wrote that can be found.

So it's quite a remarkable archive.

- It's a lot of letters, 20 books.

I am curious for the filmmakers, when you do this, is it like peeling back the onion and there's a layer and a layer.

And you, you really can't go with a preconceived notion, because I guess you don't know what you're going to find.

- Well, you know, the thing we've been saying as we've been having these conversations, and it's really true is to, if I'm honest, I don't remember what I remembered about Hemingway when I started this.

It was important to sort of check your bags and they're in some carousel in some other city.

And the preconceived notions had to go, and that's, you know a prerequisite for getting into these kinds of multi-year projects that we do.

And you get in and all of a sudden, there's a kind of familiarity and a curiosity and it's leading you in so many different directions.

And then when you're beginning to finish, and you see the kind of beginning of the end of it, that the thing is emerging as a thing in and of itself, it's beginning to talk to you and demand of you things, and it isn't just the imposition of will on it, our collective will, you then start trying to remember what exactly it was you thought.

I mean, I can remember my response to reading The Killers when I was a kid, or to Old Man and the Sea or later things.

But what I don't know is exactly who the person was after we said yes to this project.

After talking about it for decades.

And then when we said yes, and knew we were gonna do it, I just, everything has been so new.

It has been literally, as I said, the sharing of a process of discovery.

- I hope we can squeeze in just one last question.

And this is from Michael, who wants to know, "How did the Hemingway archive "end up at the Kennedy library?"

- That's a very interesting story.

And from what I understand after Hemingway, I may not have this exactly right, so I, but after Hemingway died, and his widow was able to collect all of his papers eventually from the home and from the bank vault in Cuba and just collect everything, she was approached or she approached Jacqueline Kennedy.

And basically they agreed that Hemingway was so important to the nation, that in the new JFK library, the Hemingway papers belonged there.

I think I have that right.

I'm sure I'll be corrected if not exactly right.

- Thank you Michael, for your question.

Boy, this hour went by way too quickly!

- Yeah, too fast.

- Thank you all.

Thank you to this extraordinary panel for your insight this evening.

Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, I can't say enough about how good this documentary is.

Cristina Garcia and Brin-Jonathan Butler, you made the conversation shine with your stories and your personal connections, and especially to all of our viewers, thank you.

I want to give a special thanks to our event partners, FIU's CasaCuba, The Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum, and Books and Books at the studios of Key West.

Hemingway premiers on South Florida PBS on April 5th at 8:00 PM, on WPBT and April 8th at 9:00 PM on WXEL.

And I encourage our viewers to check your local listings for when Hemingway is in your area.

I appreciate all of you spending your time with us.

Have a good night.

- Thank you, Ann.

- Thank you so much.

- Thank you.

Great to be with you.

Thank you.

Support for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for HEMINGWAY was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Annenberg Foundation, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, and by ‘The Better Angels Society,’ and...