Courtmaker: John Marshall and the Forging of America's Supreme Court

11/3/2025 | 1h 57m 31sVideo has Closed Captions

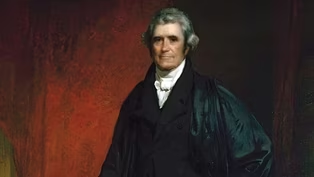

Courtmaker examines how John Marshall established the Supreme Court as a pillar of democracy.

Courtmaker explores how Chief Justice John Marshall transformed the Supreme Court into a coequal branch of government. Through interviews, stunning locations, and re-creations of landmark cases like Marbury v. Madison, the film reveals how Marshall shaped the nation's legal foundations and enduring ideals of liberty and self-government.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Courtmaker: John Marshall and the Forging of America's Supreme Court

11/3/2025 | 1h 57m 31sVideo has Closed Captions

Courtmaker explores how Chief Justice John Marshall transformed the Supreme Court into a coequal branch of government. Through interviews, stunning locations, and re-creations of landmark cases like Marbury v. Madison, the film reveals how Marshall shaped the nation's legal foundations and enduring ideals of liberty and self-government.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Courtmaker

Courtmaker is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipForged in battle.

But he made his mark in the courtroom.

The status of the Supreme Court and was disrespected and often ignored.

John Marshall's opinions shaped the country.

Historians debate whether great forces changed history or whether great men do on this issue.

A great man did John Marshall.

How this Founding Fathers influence is still being felt today.

It was under his leadership that the court became a significant player.

No one today can doubt the importance of the Supreme Court of the United States of America.

It touches every aspect of our lives and every part of our country.

The Supreme Court is the third pillar of the federal government.

It rebukes presidents and Congress.

Its decisions are often on the news.

Nominations of new members are always in the news.

But it wasn't always so.

The status of the Supreme Court, when Marshall joined in 1801 was unloved, disrespected, and often ignored.

He was the fourth Chief Justice.

Nobody remembers the work of the first three.

Marshall took it and made it into something that was of a co-equal branch.

That was under his leadership, that the court became a significant player at its finest.

The Supreme Court has been a bulwark against tyranny and popular passion, and John Marshall is the man who forged the American Supreme Court.

John Marshall is the greatest judge in American history.

Critical to America's formation.

But his formative experiences came not in court but on the battlefield.

Like his fellow founding fathers, he was shaped by the revolution.

His vision of America and of the need for a constitution, a vision to achieve.

Dedicated.

His life was forged in the fires of war.

The two men in John Marshall's life that were formative were George Washington, his founding father.

Right.

And then his father.

So this is the county where John Marshall was born and grew up.

That's right.

He's born in 1755.

And this county is formed four years later.

But this is the formative place of his youth.

So he's he's practically frontier.

It's not just practically from.

I mean, it's actually frontier.

This is this is the edge of civilization for British North America right now.

As a man in his 70s, reflecting back on on his life, he says he grew up in a time when love of the union and resistance to Great Britain were the claims of Great Britain were the inseparable inmates of the same bosom.

Yet today he was the importance of the war in shaping his outlook for the rest of his life cannot be underestimated, and I so this is where he would have left to join the militia.

That's right.

In 1775, 19 year old.

This is where he would have essentially strode into American history to go in service of an idea of political liberty and self-government.

This is a major decision that you're going to take up arms and become a traitor, which, if this fails, you will be hung.

And then the continental.

This is Valley Forge, the military camp where George Washington and his army suffered through the winter of 1778.

After the British captured Philadelphia.

They didn't have supplies.

They didn't have much food.

And yet Marshall was the best tempered man.

And his cabin mate would say, this is the worst experience in American history.

And your cabin mate is saying, you never complained and you were telling stories and just holding people together.

You get a sense of what kind of person Marshall was.

You also just see a natural leader.

He's also witnessing George Washington holding together the army at Valley Forge.

It's a horrible, trying experience, one in which Marshall appreciates firsthand in his bones the weakness, of of the government at the time.

At Valley Forge, John Marshall saw a revolution hanging in the balance.

The lessons he learned here would last a lifetime.

What Marshall Papers do you have?

Well, we have an account book of his.

Like many of his contemporaries, Marshall destroyed most of his personal papers before his death.

But deep in the archives of William and Mary College in Williamsburg, Virginia, are letters and documents that offer an intimate view of the Great Chief Justice throughout his lifetime.

Here's a document in John Marshall's hand when he was serving with the Virginia militia during the Revolution.

It shall be the duty of commanding officers of companies at every muster to inspect the public arms.

Yeah.

So if the soldiers weren't up to, snuff when it came to their inspections, they could be, fined not exceeding $2.

It's clearly in his handwriting, but it's.

He has no legal training.

But he's he's literate, of course, and, and smart as a whip.

And so he's able to digest the laws of war and to administer military justice as a deputy judge advocate general.

He learned the way lawyers in those days tended to learn by doing, by apprenticing, by by doing actual legal work in the, in the Army under Washington.

At William and Mary College, John Marshall received his only formal legal training, six months of study under George with America's first law professor and a mentor of Thomas Jefferson.

I think with wanting to instill in his students the values of being well-rounded.

So they didn't just read legal treatises, they read other books in the humanities.

They practiced moot court, they practiced in the legislature.

And also the idea behind it was to create citizen lawyers, to create people who would lead our nation into greatness.

John Marshall was in that early class of statesmen, the first alumni of George, with the first of young lawyers to lead a nation.

Williamsburg was the capital of Virginia for most of the 18th century.

Here in the rebuilt Governor's Palace, I've been invited to an annual event that takes us back to 1781, when Thomas Jefferson, Marshall's cousin, was governor and John Marshall was courting Polly Ambler.

Marshall himself was on inactive duty after the 1778 1779 campaigns.

Polly caught his eye.

She was only 14.

Your.

Thomas Jefferson.

Oh, let the rebels come in.

Falls.

We're where the elite of Virginia socialized and where their children looked for wives and husbands.

Polly Ambler, not quite 14, had never laid eyes on Captain Marshall.

Never even been to a ball.

But her sister wrote she set her cap at him and vowed to eclipse us all.

What came from this dance was the love of his life.

John and Polly Marshall moved to Richmond in 1784, where the young lawyer sets up his first law practice in the new state capitol.

Historian Charles Hobson brings me to the Richmond House.

John Marshall Bills soon after his marriage to Polly.

We only know about it from Marshall's point of view.

Through 45 letters, all of them addressed to my Dearest Polly.

Yeah, it was clearly a love match.

Over many years, and they probably spent a lot of long winters evenings reading to each other.

When he talks about they used to beguile those long winter evenings.

I love that word beguile.

This was a room where Marshall had his famous lawyers dinners.

He liked to entertain.

He thrived in and masculine company.

With his law practice prospering, Marshall and his public service.

Elected to the Virginia House of delegates in 1787 as a staunch Federalist, Federalists were the people who wanted a stronger national government that felt that the Articles of Confederation weren't powerful enough, really, to hold the states together and to accomplish what they thought a central government had to do.

The Articles of Confederation, which preceded the Constitution of the new nation, had been a pact between the states.

The Articles of Confederation had no executive or judicial or, common legislative functions, with the power to tax and to defend.

All of the states were sovereign, and the Anti-Federalist believes that they maintain that sovereignty.

Federalist and disagreed.

They insisted that we, the people of the United States as a whole, have the sovereign power, and Philadelphia delegates from across the country are forging a new path for their new nation.

From May to September in 1787, a shifting cast of 55 men would write a new constitution for the United States.

John Marshall knew a lot of the men in this room.

His law client, George Mason, would oppose the Constitution at the end and refused to sign it.

Alexander Hamilton, his comrade from Valley Forge, would sign and would argue for the Constitution in the Federalist Papers.

The presiding officer of the convention and the most important delegate was the man Marshall had obeyed for five years.

George Washington.

He was the first to sign and his large rolling hand, and he would lobby vigorously for ratification.

Behind the scenes, it's so striking to think of these men who came to Philadelphia to debate the Constitution and the personal dynamics among them, debating people who disagreed strongly during the day about fundamental questions like the nature of federal versus state power or slavery and freedom, led by a few distinct individuals, many of whom had known each other and grown up with each other.

The new constitution is controversial, and many oppose it.

In The Federalist Papers, Hamilton and his colleagues argue passionately for its passage nine of the 13 states must ratify it for it to go into effect, and Virginia, the largest, is a must have.

Marshall throws himself into the fight for ratification.

There, while Thomas Jefferson, now America's ambassador to France, is much less enthusiastic.

He believed in the American nation, but he believed it was a nation of states.

John Marshall is Thomas Jefferson's cousin and the relationship between these two men will dramatically impact America's development as a nation.

The Jeffersonian feared that the Federalists really wanted to reestablish a monarchy, the very, very thing we had overthrown in the, in the Revolutionary War.

Many people considered Virginia to be the epicenter of what comes to be known as the Jeffersonian Republicans.

And Marshall is a Federalist in Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall had a very complicated relationship.

There was a sense of mutual respect in that, in a way that maybe to tigers, in a, in a cage would have some mutual respect.

They were opposites politically, really for for their whole, for their whole life, this political difference between the two cousins will only grow.

But there are personal differences, too.

Marshall served in the revolution.

He was at Valley Forge with his men, and Jefferson was not a soldier.

I mean, in that day and age accounted for a great deal.

The ratification of the Constitution was controversial in Virginia, and the ratification and debates in Virginia are wonderful microcosm of the competing arguments for and against the Constitution, the Jeffersonian spirit, a very strong central government, one that would crush the rights of individuals and would crush the authority of states.

When you think about what happens in 1860, when you have a civil war, that is very much a continuation of this battle of, whether you're going to have state sovereignty and state power versus national sovereignty and national power.

It was this fundamental political difference, of course, that ultimately translated into the political party system in the early period.

Were it not for Washington's shining reputation, the fact that all the delegates from North and South acknowledged his greatness and his neutrality, the convention would never have been successfully summoned and the Constitution would never have been ratified.

Virginia is the 10th state to ratify the Constitution, and in June 1788, marshal and crowds across the new nation celebrate.

Ten months later, in April 1789, the country celebrates again as Marshall's mentor and hero, George Washington takes the oath.

This first president of the United States.

The 1790s was a really intense, passionate, and often unpleasant decade.

People are realizing, you know, we fought this war and we created this country, but we now have some different understandings about what that actually means.

People really don't know what kind of nation it's going to be, or even more significant, if it's going to survive at all.

By Washington's second term in office, factions are already splitting his cabinet.

Jefferson and his allies support France, America's Revolutionary War ally, while Washington, Hamilton and the Federalists support Britain, America's chief trading partner to everyone.

Shock George Washington, who could have reigned for life, decides I am not a king.

We have to establish from the beginning the president of the United States is not like the King of England.

I hereby retire the United States was a new nation.

It was tiny.

It wasn't really in any way militarily strong.

And for much of the 1790s, it was being bounced back and forth between France and England.

Jefferson is a strong believer in the French Revolution.

We Americans should be grateful for the French who came to our assistance at Yorktown, and without whose military assistance we would never have won.

Ridiculous, says John Marshall.

We have to understand that it's the British who control the ocean.

And if we ally ourselves with the French, the British are going to invade us again.

John Marshall became the Federalist Party's champion in Richmond, defending its foreign policy in public rallies and here as a member of the House of delegates.

So the French are upset that the Jay Treaty was signed and American relations with England seemed to be going swimmingly.

And there seem to be economic implications of that.

And as happens throughout this period, the French do not like this.

So they respond by starting to intervene with American shipping at sea.

In 1797, the incoming president, John Adams, taps Marshall and two others for a vital diplomatic mission.

On the visit, we're on board the U.S.

Coast Guard ship Eagle, seventh of its name, sailing into the North Atlantic as Marshall did in 1797.

The U.S.

Coast Guard is a direct descendant of Alexander Hamilton's Revenue Cutter Service, and the first two Eagles fought in the undeclared conflict with France, known as the Quasi War.

It's essentially a diplomatic misunderstanding that snowballs.

French Foreign Minister Talleyrand tells Marshall and his colleagues that the price of peace will be money up front to France, and bribes for him.

Marshall reveals the shakedown in a coded report, Home News that ignites a political firestorm across America.

This becomes this great moment of outrage, where Americans are insulted that they're being asked to pay tribute to a foreign nation and the United States starts building up the army and preparing for this quasi war.

Marshall arrives home on June 17th, 1798, and finds himself a hero for one of the few times in the 1790s, the Federalist Party.

Marshall's party is getting a lot of popular appeal.

Jefferson and his pro French Republicans are furious by making France seem hostile.

Marshall has made them look un patriotic, and the rift between the two parties widens.

He called it a dish cooked up by Marshall.

Yeah, yeah, he's distrustful of these people because he thinks that they're disloyal to the American Revolution.

These are very powerful, intelligent men who are just despising one another and public.

Then, in the fall of 1798, Marshall received a pressing invitation from George Washington to come and visit at Mount Vernon.

Washington very earnestly urged Marshall to stand as a candidate for the next Congress to represent the Federalist Party, and Marshall refused any idea of stepping back into public life.

But Washington's passionate argument for public service eventually wears Marshall down, and Marshall said, I yielded to his representations and became a candidate for Congress.

Marshall was a High Federalist, which means he was a nationalist in Alexander Hamilton's mold.

He was a disciple or a protege of, Alexander Hamilton.

At a time when there was political pushback against a strong central government.

In December 1799, John and Polly Marshall come to Philadelphia, where John takes his seat here in the House of Representatives, John's Federalist Party is riding high.

They control the white House and both houses of Congress, but they're engaged in constant struggles with their rivals.

The Republicans, and with each other.

Marshall is in some ways helping Adams carry on Washington's legacy, but Adams is dealing with a Federalist party that is spiraling, out of out of control.

It's falling apart.

George Washington's death in 1799 seems to unleash the inner demons of federalism.

And it comes after a decade of feuding between the Federalists and the Republicans.

Politics in 1800 was a contact sport.

Today, we wring our hands over rough politics.

But the founding fathers fought each other and they fought hard.

There were real ideological differences, for example, over what the proper role of the federal government was and what its relationship to the states would be.

In the midst of this battle for America's soul, President Adams fires his Secretary of state and appoints John Marshall to the position, just as the seat of government leaves Philadelphia in June 1800, President Adams and Secretary of State Marshall moved to the new capital city, named after George Washington.

After a week, Adams went to Massachusetts to tend to sick wife and Marshall moved into the white House to run the executive branch until the president returned.

He's probably after Adams, the brightest star on the Federalist side.

The election of 1800.

The incumbent, John Adams, loses to Jefferson, and the Federalists are very much on the defensive and out of power.

This is the first major case of a democracy facing the question of a transfer of power from one political party to another political party, but it wasn't clear that that was going to happen.

When John Adams loses the election of 1800, one of the ways that he thinks the Federalist can continue to exercise power into this new era of Republican control is by gaining the reigns of the judiciary.

And so he passes a law.

With the help of Congress.

He passes a law that creates a new judgeships and also a whole bunch of new justice of the peace commissions.

In the waning days of his administration, from his office in the still unfinished white House, John Adams filled the judiciary with fellow Federalists, the Midnight Judges.

In December, he got a letter from then Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth saying that he must resign because of ill health.

Adams nominated John Jay, who had held the job in the Washington administration, and the Senate approved that.

In January, Secretary of State Marshall handed Adams a letter from Jay.

Dear sir, I've been honored with your letter informing me that I had been nominated to fill the office of Chief Justice.

I left the bench perfectly, convinced that it would not obtain the energy, weight and dignity that are essential to it.

Hence, I am induced to doubt both the propriety and expediency of my returning.

I am, dear sir, you are a faithful friend and servant.

John Jay Adams asked Marshall, who shall I nominate now?

Marshall said, I don't know, sir.

Adams said, I believe I must nominate you.

Marshall bowed silently.

And then John Marshall is now both Secretary of State and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

On March 4th, 1801.

He administers the oath of office to his cousin, Thomas Jefferson.

The Jeffersonian feared that the Federalists, though defeated at the ballot box, would try to govern the country through the federal courts, since, after all, the federal courts were entirely in the grip of members of the Federalist Party.

The Federalists said President Jefferson had retired into the judiciary as into a stronghold.

One of the main items on his agenda would be breaking Chief Justice Marshall and his stronghold down over the next 34 years, John Marshall Supreme Court will hear more than 1100 cases.

Many will have a lasting impact on America down to the present day.

One is a case that comes before Marshall late in 1801 that will put him in direct opposition to his cousin and the new Republican majority in 1800.

William Marbury is a successful banker and a real estate speculator.

I'm here at the home he built in Georgetown, on the outskirts of the new federal city.

Marbury was a stout Federalist.

In recognition of his loyalty, he was named a justice of the peace of the District of Columbia by outgoing President John Adams.

Marbury was one of several midnight judges to several judges who were appointed at the end of what administration before the beginning of the other.

John Marshall, in his capacity as Secretary of State, is in charge of writing out commissions.

To all of these gentlemen.

And they're all, of course, gentlemen.

And most of them had their commissions delivered sort of in an overnight rush before the handover of the reins of power from the Federalists to the Republicans.

Marbury had been appointed.

His commission had been sealed, guaranteeing the authenticity of the appointment.

But the paper never got delivered.

The commission never got delivered.

In the confusion at the end of the Adams administration, when Jefferson became president and Marbury requested the delivery of his commission, the executive branch said, nope, we're not going to give it to you.

Jefferson thought that, having been made president, he should have the right to make these kinds of appointments.

He saw this as an attempt to extend Federalist rule through the judiciary, through any means necessary.

And so he did see it as an attack on his power.

Marbury tries for months to find out what happened to his commission, but everyone in the executive and then Congress, both firmly and Republican Party hands stonewall.

So finally he goes to the Supreme Court asking it to issue a writ of mandamus to James Madison, Jefferson's secretary of state.

And what a mandamus is, is an order from the court ordering somebody, a government official, to do something that the government official has a legal obligation, an obligation under statute or under the Constitution to do Jefferson's new Judiciary Act cuts Supreme Court sessions to one a year.

So it's almost two years before Marshall hears Marbury case.

Why did he take it?

He took it because he saw that the Jeffersonian were about to undermine the Federalist vision of the Constitution in the country.

And if there was going to be a fight about it, he was going to be on the front lines.

And if Jefferson was on the other side, so much the better.

I mean, they hated each other and he was going to defend the the court and the Constitution against the Jeffersonian, revolution.

It was an exercise of separation of powers at a very critical moment in American constitutional history.

The relationship of the three branches of government simply had not been defined up to that point.

It was a work in progress.

Six justices, all Federalists, including Marshall, will decide the case.

With justice Chase immobilized by gout, the court conducts its business in a Washington boardinghouse, where the justices live together while the court is in session.

Peculiar delicacy of this case requires a full explanation of the principles on which the opinion is founded.

When a commission is signed by the president, the appointment is made to withhold William Marbury Commission.

Therefore, as an act that violates a vested legal right for which the laws of his country afford him a remedy.

But then we get the rub.

Does this court have the authority to write the wrong?

Marshall doesn't want to go there because Marshall doesn't actually want to decide the case.

And the reason he doesn't want to decide the case is because he's pretty sure that if he sends a writ of mandamus to James Madison, Madison will ignore it.

Under Jefferson's orders, his court is quite weak at the time.

Jefferson is quite strong at the time.

Jefferson controls not just the presidency, but basically the Congress as well.

Marshall wants to avoid a crash between the court and the president, because Marshall knows he's going to lose.

He ends up giving a disquisition on the law that cast Jefferson as a lawbreaker, as someone who'd taken away something that Marbury was entitled to.

But then he pivots from that to a discussion of the court's jurisdiction.

Okay, so article three of the Constitution, which sets out the powers of the Supreme Court, says that in a certain class of cases, the Supreme Court can have original jurisdiction, which means the case begins in the Supreme Court.

That's what Marbury is trying to do.

Marbury has brought his case under a 1789 act of Congress, allowing the Supreme Court to issue mandamus threats to anyone holding federal office.

But the Constitution only gives that original jurisdiction in a very limited class of cases.

That doesn't apply here.

And when the Constitution and the law disagree, says John Marshall, the Constitution is paramount.

While ostensibly declining to exercise power, he hasn't been granted exercising judicial modesty and restraint.

He's actually asserting a grander, much more decisive and important power.

It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.

The Constitution is a superior, paramount law, unchangeable by ordinary means, and no ordinary act of Congress may govern any case to which they both apply.

Consequently, an act of the legislature repugnant to the Constitution is void.

The rule requiring the Secretary of State to show cause is therefore discharged.

The case is known for, and it's most properly famous for its recognition that the Supreme Court can hold an act of Congress unconstitutional.

Is the one that is fought to establish judicial review.

It is important because of the way that he did it, by coming out in a particular way, which goes against what you would think he would be for here.

He's refusing to do something in the interest of his own political party, the Federalist Party.

Marbury does not get his reps, and technically they.

Administrations wins.

Jefferson is outraged by the decision, but there's not a lot he can do about it, and that's what makes it so beautiful.

I mean, Marbury loses, so it's not beautiful for Marbury.

And the fact is, nobody cares whether William Marbury gets a commission.

But the legacy of the case endures, which is the power of judicial review.

So this is this brilliant move which we're going to see time and again in Marshall's career of political statecraft.

The case that Marshall chooses to announce the authority of judicial review is actually a case for Congress is trying to enlarge the power of the court.

Hey, smart, crazy, a little bit of both.

Why do you think he did that?

It's a decision that echoes down through time at the College of William and Mary and Williamsburg, Professor Larson takes her students to a local tavern to discuss cases, just as George Swift did with Marshall and fellow students back in the 1770s.

It's like a natural byproduct of of creating the Constitution itself.

I think that is exactly what Marshall would say, that it's it's inevitable.

It's part of the function of constitutionalism is to have a neutral arbiter.

And Marbury versus Madison is often the focus of discussion.

There's plenty of other democracies out there, like England, where their courts do not have the power of judicial review.

So I think it's useful for us to think about why did Marshall think it was so important for judges to have this power in our democracy?

What makes us unique or what makes his reasons so powerful?

I would have to say that judicial review, the power of unelected judges to review the constitutionality of laws enacted by the elected representatives of the people, and, if necessary, hold that they are unconstitutional and therefore unenforceable, is the greatest American contribution to jurisprudence more determined than ever.

To break Marshall's hold over the Supreme Court, Jefferson adds three Republican justices.

By 1807, filling two vacancies and increasing the overall number to seven.

One reason people were reluctant to serve on the Supreme Court was the justices had to ride a federal circuit, one justice called the assignment intolerable.

Marshall circuit included Richmond, where he lived, and Raleigh, North Carolina.

Twice a year.

He made the 170 mile trip there and back.

And it says a circuit judge that he will next clash with his cousin, Thomas Jefferson, when he presides over Vice President Aaron Burr's trial for treason.

Aaron Burr was a brilliant, brilliant and powerful person, extremely well-connected and extremely ambitious.

Thomas Jefferson hates Aaron Burr, and he hates Aaron Burr for a variety of reasons, but most of them stem from the election of 1800.

Jefferson runs with Aaron Burr.

It's Jefferson and Burr, the presidential electors under the existing Constitution vote for two people, and whoever got the most votes was president.

Whoever got the second most was vice president, regardless of party.

But there's a tie between Jefferson and Burr, and the Constitution says if there's a tie, then the House of Representatives chooses between the two and Jefferson's party doesn't control the Congress altogether.

So some Federalist, some anti Jefferson folks, they lost the election, but they still have the ability to to basically make some mischief by picking Burr over Jefferson.

So you go through ballot after ballot after ballot.

Alexander Hamilton, staunch Federalist and no friend of Jefferson, believes him the lesser of two evils, considering Burr a man with no principle on the 36 ballot.

Hamilton's backing tips the scales.

Hamilton has thrown his support to Jefferson, and now Jefferson is president for his vice president.

Jefferson never forgive spur for this.

Here was Burr sitting as vice president who has no job other than to preside over the Senate.

Being a pariah so far as Thomas Jefferson is concerned.

The thing that, of course, climaxed, Burr's demise was the fact that he shot Alexander Hamilton in the famous duel in 1804.

And so Burr finds himself an outcast.

Burr now is no longer vice president of the United States.

He's killed the great Federalist champion and John Marshall's hero, Alexander Hamilton.

He's a man without a party, a man without principles.

What's he going to do?

I he does what every young American does that is out of luck.

In the East.

He goes west.

We're sailing down the Mississippi River to New Orleans.

Crown jewel of the Louisiana Purchase, bought by Thomas Jefferson in 1803, the city control the trade of the West and offered a gateway to Mexico.

No wonder the United States wanted it.

When Jefferson buys almost 900,000m of land west of the Mississippi River from France, the Louisiana Purchase, he doubles the size of the new nation overnight.

Westward expansion is in the air, and opportunities for land and riches seem limitless.

Well, Burr seizes opportunity here.

Maybe he can find a way to have some degree of power, to have some degree of influence, to find a place where he can have some importance and engage again in leadership and politics.

From the very moment that he headed west, rumors began to circulate.

What actually is he doing out in the West?

James Wilkinson as governor of Louisiana and general of the United States Army, Wilkinson probably is one of the most Machiavellian characters in the early Republic, and he assumed that there was eventually going to be war between the United States and Spain.

Wilkinson is initially a willing partner in Aaron Burr schemes.

The accusation is that he's creating an army of his own.

Not only was he interested in invading Mexico, but he was going to sever the West, and then he was going to create his own independent country, and he's going to set himself up as a kind of American Napoleon.

I'm at blunder House, that island on the Ohio River in what is now West Virginia.

Late in 1806, a party of armed men set off from here flatboat to rendezvous with Burr downriver.

What they were doing would decide Aaron Burr s fate at his trial.

As rumors spread of Burr's activities, General Wilkinson betrays this friend.

He writes to President Jefferson, accusing Burr of a deep, dark, and widespread conspiracy to sail down the Mississippi with 7000 men, seize New Orleans, and invade Mexico.

The muster of 60 men at Lennar House.

This island will be portrayed by the prosecution as a visible proof of treason.

This is the power of political gossip, the power of how one's negative image followed him and Thomas Jefferson, who is still present, is very willing to believe every piece of dirt, every piece of gossip that's reported to him about Aaron Burr, Thomas Jefferson, like a lot of other people, thought that Burr was not only a scoundrel, but a danger.

Jefferson had a vision of the United States in the West, in particular, that this was going to be part of America, the United States of America, an empire for liberty or empire of liberty.

And anything that interfered with that we thought was a threat.

This was a young and vulnerable republic.

Its future was the reverse of clear.

No one knew where this experiment and republican government would go.

Previous republics at all failed.

When they failed, they always ended up in the hands of a strong man, of a demagogue, of, of a power hungry maniac.

And, Jefferson saw Burr as someone who might very well fit that, fit that role.

In January 1807, Congress received an electrifying message from President Jefferson Aaron Burr, former vice president, was plotting to invade Mexico and break up the United States.

The evidence was not yet formal and legal, but Jefferson assured Congress that first guilt was beyond question, and the question is who is going to try him?

None other.

And John Marshall, who has a complicated, to put it mildly, relationship to Thomas Jefferson Marshall will hear the case because Brenner has set Ireland a key location, and Burr's alleged conspiracy falls within his circuit.

I'm and Colonial Williamsburg, a place where it's still possible to recapture a sense of everyday life at this pivotal time in American history.

In the courtroom of the old Capitol, present day lawyers argue whether there is sufficient evidence to indict Aaron Burr on the crime of treason.

Counsel, please state your name for the record.

Judge Roger Gregory of the Fourth Circuit, Marshall's old circuit sits in judgment.

Councils for prosecution and defense are practicing trial lawyers.

Kevin Walsh only the defendant, Aaron Burr, is portrayed by an actor.

Aaron Burr has been arrested and now comes before the court for a preliminary hearing on the charge of treason and assembling an armed force with a design to seize the city of New Orleans and to separate the western and the Atlantic states.

This charge is punishable by death.

The government shall present its evidence in support of probable cause for this charge.

Thank you, Your Honor.

First, we have an affidavit from General Wilkinson.

The commander of U.S.

Army Forces in New Orleans.

As General Wilkinson's affidavit recounts General Wilkinson's testimony and letter to President Jefferson as primary evidence against Burr, as a justice who writes, the case will ultimately come down to the general's own credibility in front of the grand jury trial arguments are drawn from original trial transcripts.

This is not where we are deciding whether this man will be convicted of treason.

The court right now is deciding the limited court is quite aware of the burden of proof at this stage is probable cause.

John Marshall has a very strict standard for what counts as treason.

Treason isn't just loose talk.

We are just asking for the information that the president has declared he has.

And rather than provide this basic information, his proclaimed Aaron Burr a traitor to the country, just let slip the dogs of war the hellhounds of persecution to hunt down my friend Aaron Burr, who was the best lawyer on his own side to Marshal, I need to see this key piece of evidence that Jefferson used to bring his charge of treason in President Jefferson's communication to Congress, dated 22nd January, 1807, to both houses of Congress.

He speaks of a letter and other papers, receipt from General Wilkinson, dated 21st October.

Person to marshal.

Hey, look, I want you to order the president of the United States to deliver this piece of paper in your possession.

Jefferson says I'm present in the United States.

I have a lot of sensitive information, and you can't force me to actually disclose that.

It would be remarkable for this court to command that a private correspondence to the president of the United States, John Marshal, is now once again faced with a decision.

Does the court really want to walk down that path of forcing the president to disclose very sensitive documents?

On the one hand, is he going to force Thomas Jefferson to reveal sensitive national security diplomatic secrets?

I hand, is he good to deny Mr.

Burr his fair trial?

Is not the court able to in-camera look at those documents and determine whether or not there are things on the sensitive nature that you suggest.

Aaron Burr's request for a subpoena was a powerful courtroom reversal.

The letter from General Wilkinson got the whole process started.

But when Aaron Burr asks that President Jefferson produce it, he forced Jefferson into a defensive crouch, defending his own prerogatives and position.

Chief Justice Marshall decides that the president can be subpoenaed, forcing Jefferson to provide Wilkinson's letter, and was reluctant if in any court of the United States it has ever been decided that a subpoena cannot issue to the president, that decision is unknown to this.

I said this was a big victory, not only for Burr, but for Marshall and the judicial process, because it proved one thing that the president of United States is not above the law.

And Jefferson himself conceded that point when he delivered the papers as the government.

In spite of Marshall's reservations, the grand jury indicts Burr for treason crimes.

The full trial begins in August 1807, and Virginia's House of delegates, with Chief Justice Marshall again presiding.

The theater involved.

The legal theater involved was extreme.

Apparently people were camping out along the riverfront just south and below the Capitol proper, waiting to see what the next developments in this long case might be.

Knew the old House of delegates Chamber and the Virginia Capitol building, where Aaron Burr's trial took place, is now a museum.

I guess the floor no longer has the sand filled boxes that were intended to capture at least some of the chewing tobacco that was being great.

Arguments were made on both sides of the question.

The prosecution was prepared to call 140 witnesses, but Marshall stopped testimony after hearing only a dozen because no overt act of treason was proven.

Indictment charges the prisoner with levying war against the United States, and alleges an overt act of levying war.

That overt act must be proved by two witnesses.

It is not proved by a single witness.

Jefferson fumes in the white House as the jury acquits Burr of treason, and there's widespread anger across the country.

Marshall and Burr are burned in effigy in Baltimore.

Marshall writes that the Burr case is the most unpleasant ever brought before a judge.

And then, very tellingly, Marshall says, I may perhaps have made it less serious to myself if I had followed the public will instead of the public law.

The Virginia Argus newspaper said that his performance in that trial showed that an independent judiciary is a very pernicious thing.

Marshall's steadfast adherence to the Constitution, even in the treason trial against the unpopular Aaron Burr, showed just the opposite that an independent judiciary is a very precious thing.

That's the great accomplishment of Marshall, to make the Constitution interpret the Constitution as law, and the role of the court as preserving it against the political branches.

I would just and emphasize how important he is to the fact that we live under, under laws rather than under men.

But Marshall's life isn't wholly consumed by the law.

I'm on a better James River flat like those that Marshall on a survey team took up river in 1812.

The state of Virginia has commissioned him to see if the James can be linked to the Ohio River by a canal, competing with New York for advantage in establishing Western trade routes.

And when Marshall did his 1812 survey, he did it in September because he wanted to be on the water at the lowest time of the year to see is this route going to be feasible at its hardest?

They're still talking about these United States and not the United States.

For the health of the Union, it was imperative to cement political and economic ties with the people of the Midwest.

He's also thinking as a as a a nationalistic Virginian, you know, he he wants to benefit Virginia by tying the union together through Virginia.

This connected him with George Washington, who dreamed of such a route years before, connected him with his father, Thomas, who had been a surveyor.

And it got him away from an election his party was losing and from a war he didn't want America to fight.

First, they had been France and the United States in the quasi war, banging up against each other.

And then, of course, the next problem becomes the United States and Britain.

The British are intervening with American shipping.

It becomes something that seemingly can't be resolved in any way.

Jefferson's, fanatical opposition to the British precipitates as a War of 1812.

The Federalists are really, really aggressively anti war as a party.

Their identity was partly bound up with the British.

They also, economically and in every other way, felt that it was really important to maintain ties with the British because they strongly oppose the war.

Federalists appear unpatriotic and their national reputation suffers.

After the war, the party collapses, but the judiciary is still firmly under John Marshall's control, and another case from what only recently has been the frontier will pit it against the ruling Jeffersonian Republicans.

Dartmouth College was this college who had been set up originally to serve vengeance.

The founder was a year who had gone up with a Bible and drum.

And oh, how many gallons of New England rum is the story?

Evolving from a school and Indian country into one of the first colleges in North America, Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire becomes another battleground between John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson, no longer in the white House, but still pulling the strings of Republican politics.

Dartmouth College was a haven of Federalists in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire, on the other hand, was governed by Republicans, and they did not want Dartmouth College to be a bastion of, Federalist, thought the Republican governor of New Hampshire is William Plumer.

William Plumer, how would you characterize him politically?

Oh, he used to be a Federalist.

Right.

And after the War of 1812, when the Federalist Party had more or less lost its bonafides and credibility, he converted right Republican ism, and he became a Jeffersonian, Democrat.

And he saw the college as a political instrument for developing not only his strength as a political figure, statewide, but nationally.

The state wanted to turn Dartmouth into a public university.

They say we are tired of having this private college training, the elite training our political opponents.

Let's dismantle Dartmouth College as it exists, make it into a state university.

And so they pass a law that, makes Dartmouth College essentially a public college, no longer a private college.

And that places above the Dartmouth trustees, a new board that is selected by the state of New Hampshire and Dartmouth College of Woodward is a suit between the old Dartmouth College and the new Dartmouth College, who was Woodward.

Woodward had been treasurer of Dartmouth College, and he, looking at the new legislation, decided to cooperate.

So he agreed to become treasurer of Dartmouth University.

A new Dartmouth University now holds the seal charter and college buildings, and the old college wants some back.

There's much at stake here.

If New Hampshire can so easily take over Dartmouth College, what's to prevent other state governments from taking over other private colleges across the country, like Princeton and Harvard?

So how does the lawsuit start?

The trustees said, we're the initial contractual partners, and we refuse to obey the governor's edict.

So the case goes to the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

And what do they rule?

They rule in favor of Plumer and, favor of the governor.

Back for the governor.

It looked airtight.

The Dartmouth College case is argued by Dartmouth's most famous alumnus, Daniel Webster, who one of the great lawyers at the time, Daniel Webster, still in his mid 30s and a budding Federalist politician, as well as a lawyer, will use all his intellectual and rhetorical powers to defend his beloved alma mater.

Webster thinks the next step should take it to the Supreme Court in order to have the court decide on whether or not a state has sovereign power to violate conditions of a contract.

Following the example of John Marshall and his fellow justices, I've invited a group of legal scholars to dinner.

The Jefferson Hotel in Washington, DC, to discuss the Dartmouth case.

Dartmouth College is not about opening up a higher education.

It's not a vision of, an ecumenical vision.

Right?

And after they heard a case, they would retire to the boardinghouse and they would discuss the case for a long time, have a drink at dinner.

And that lubricates the the social interaction of the seven justices now on the court, five have been appointed by Republican presidents, including Joseph Story, who becomes like a son to Marshall.

Some of the justices who have been the most effective have been the ones who are able to earn the trust, of their colleagues and, made colleagues feel comfortable, talking with them.

But let me be devil's advocate here.

Education is very important.

I mean, it just is.

And so why not open up to all views?

What's the matter with that?

Deal's a deal.

You had a contract.

You had a charter, and you're going to take that one to the bank, you know, and that's what a contract is.

But the point is, the governor of New Hampshire wants to, steal the assets of the trustees of Dartmouth College for the people of New Hampshire, because he doesn't want to actually appropriate money to build a state university.

He has a lot of support for what it is that he's saying.

Justice Marshall saw that, the Supreme Court justices were divided in the case.

Really a question he wanted to develop the consensus on the case before he pronounced his decision.

Is it so now the court is speaking with supposedly one voice, and in Marshall's case, it was typically an opinion written by himself.

The opinion appears more powerful, more impregnable.

It's more authoritative.

This was a genius.

And Marshall was able to do this because of his personality.

And it was ever since that day until this day, that, Supreme Court opinion started to be studied as though they were the law.

He says, you can't take a private college and make it public.

He said the question before him was whether the charter was a contract within the meaning of the contract clause of the Constitution, but that provision was clearly even Marshall recognizes it wasn't meant for this kind of situation.

One big problem is why is the charter a contract?

Marshall just announces, as he does want to do?

Marshall says, we understand it wasn't written for this, but although it might be a rare case, the contracts clause applies here.

So what he's doing is finding a way to use federal authority to police state authority over contracts.

Marshall doesn't have to work his way through previous precedents as modern courts do.

He gets to make the precedents and courtyard line for victory.

In a landmark ruling, Marshall affirms Webster's argument and holds that Dartmouth's charter is a legal contract protected under the Contracts Clause of the U.S.

Constitution.

The state of New Hampshire may not unilaterally alter or imperil Dartmouth, would remain a private college, and not become a state university.

But Marshall's opinion was so much more than a victory for just Dartmouth.

And of course, it was a magna Carta, not just for private colleges and universities, but for private corporations more generally.

It helps spur economic development throughout the growing nation.

Again, it's sort of Marshall's vision of what kind of country, the Constitution was going it's going to shape and the importance of, contractual agreements.

I don't know if he was a, had a good sense of economics or not.

But that became such an important principle in the growth of the country throughout the second decade of the 19th century.

America is growing rapidly.

And Marshall, like his heroes, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, believes only a strong federal government and a strong national economy can hold the new nation together.

This is a printing press of Marshall's youth, but throughout his life, print was like today's social media.

Marshall and his critics were just as mean, maybe because they were all neighbors living together in Richmond.

They used pseudonyms, but everyone knew who wrote what.

Four weeks after the Dartmouth decision, Marshall's court heard a case that pitted the powers of the federal government versus those of the states.

His decision in McCulloch versus Maryland was attacked by critics and Jefferson's Republican Party, egged on by the ex-president himself.

For the only time in his life, Marshall took to the press to defend himself.

The issue is who makes money?

Do you have a national economy?

Do you have a national bank?

Do you have a national currency?

The issue was whether Congress could charter a bank of the United States.

I mean, you might say, well, how could it be an issue?

Because Congress had already chartered the Bank of the United States in 1791, had run for 20 years.

The Bank of the United States was controversial from the very beginning, in the 1790s.

When it first comes up, Hamilton raises it, and when it first comes up, Jefferson is quite opposed to it.

The Bank of the United States prompted the first major debate in America about the scope of Congress's power to regulate the national economy.

This is the headquarters of the Federal Reserve, the successor of the Bank of the United States.

Randall Quarles is vice chairman of the Federal Reserve System.

Mr.

Powell, how do you do?

Thank you.

Thanks for having me.

Oh, thanks for being here.

Why does a country need a central bank?

It provides a stable currency for a country.

It regulates the banking system and the financial system of a country or financial system.

What was Alexander Hamilton trying to accomplish when he proposed the first Bank of the United States, evident at the time that the first Bank of the United States was proposed.

The financial system of the US was, you know, absolutely an embryo.

There was no coordination between Congress and the individual states, with local banks and businesses issuing their own banknotes.

They had neither the scale nor the trust, to really provide the type of financial support for what would be a rapidly growing economy and then you had continuing through that time, the political and economic concerns about concentration of power and the continuing questions about constitutional legitimacy that ultimately led to the demise of the first Bank.

No sooner had the first bank ended, and then we had the War of 1812 and the financial and economic upheavals of that war reinforced in the minds, really, of everyone, the usefulness of a central bank.

The debt we ran up in the War of 1812 caused even many Jeffersonian to change their minds and say, well, you know, we really do need this bank as a matter of public policy.

So we'll avert our gaze or we'll hold our noses and we will permit a second bank to be chartered.

But the second bank got off to a pretty bad start, staffed by speculators and people who are interested in a quick buck, in the rising value of war debt left from the War of 1812.

In some cases they, engaged in practices that, I think were pretty clearly fraudulent.

That particularly happened in Baltimore.

By 1819, Baltimore was the largest city in the American South and a powerhouse of trade and industry.

Maryland has passed a law imposing a tax on out of state banks, banks that haven't been chartered by the state of Maryland.

And oh, what a coincidence.

There's only one bank that this applies to, and it's the Bank of the United States.

James McCullough is the cashier of the Bank of the United States, and it is up to him to pay these taxes.

He does not pay the taxes, and the state of Maryland sues him to get the taxes for the state of Maryland.

And the second bank agreed to a suit that will test the state laws.

Constitutionality.

The governor calls the case an amicable arrangement, and when the state court decides against the bank, McCulloch appeals to the U.S.

Supreme Court.

This comes before the court, and there are two main questions in the case.

The first question is whether the federal government has the power to create a bank at all.

And then the second question is, well, if it's permissible for the bank to exist at all as a federally chartered bank, can Maryland tax the bank?

And the court answers both questions in favor of the national government, because it's a properly federally chartered bank and states can't undo what the federal government has properly done?

That's actually not the most interesting part of McCulloch versus Maryland.

The most interesting part of McCulloch versus Maryland is why the bank wins, how Marshall chooses to explain his result.

Marshall answered the first question.

Yes, Congress had the power to charter a bank, even though that is not listed among Congress's enumerated powers.

And therein lies the problem, right?

The the federal government is supposed to have enumerated powers.

Only those powers that are listed in the Constitution.

But there is nothing in the Constitution that says you can do it back.

The phrase we must never forget it is a constitution we are expounding comes in the case of McCulloch versus Maryland.

What does that mean?

It seems to suggest that a constitution is not a statute.

A lawyer's document, a technical series of rules that have to be applied in the strictest and least forgiving way.

Marshall and his six fellow justices have now been together for seven years, and the chief justice is at the height of his power and influence.

Marshall decides that although the power is an expressly granted to the United States to charter a bank or other corporation, it is implied by the Constitution.

Marshall relied on a clause from article one, section eight of the Constitution Congress may make all laws which shall be necessary and proper to executing its enumerated powers, or, as Marshall put it, let the end be within the scope of the Constitution.

All means adapted to it and not prohibited are constitutional.

Did Marshall think he was interpreting a living constitution?

It's a clever metaphor.

It's an attractive metaphor.

Who wants a dead constitution?

If you mean a document that was malleable and could be shaped to the particular purposes of the people interpreting it, the answer is definitely no.

On the other hand, if you're talking about a document that would remain relevant despite changes in society, well, very much I think he he thought that the Constitution doesn't decide every question, that it leaves a lot of questions to be decided by Congress and by the president.

It leaves a lot of things to the states, and it necessarily speaks in general terms.

And those terms have to be applied to new situations that often could not have been anticipated at the time when it was adopted.

John.

Marshall decides not only that the bank is constitutionally permissible, but that the efforts of Maryland to tax the bank or constitutionally impermissible, the power to tax involves the power to destroy and the power to destroy may defeat.

The power to create.

The states have no power, by taxation or otherwise, to retard, impede, burden, or in any matter control the operations of constitutional laws enacted by Congress.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of the State of Maryland is therefore erroneous and must be reversed.

The state's rights people hate McCulloch because of its implications, and is all the more brilliant because he's getting justices who have been appointed by Jefferson and by Madison to join this opinion.

He gets a unanimous court.

Temperaturs round Harve Jefferson called Marshall and his colleagues secure for life and skulking their responsibilities.

Marshall called Jefferson the most ambitious and unforgiving of men.

Their struggle would go on, but Marshall had established the Constitution as the People's Act and therefore Supreme.

In a vault at the New York Historical Society, James Bhasker, president of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, shows me how painful the fallout from the McCulloch decision is for John Marshall.

A letter, actually, in John Marshall's hand there, he is, Richmond, okay, from his main residence, 1823.

So this is, four years after the McCulloch decision.

But the issues that it raised and the passions that it raised are still political matters.

And he's writing to his correspondent about Mr.

Johnson, who is Senator Richard Johnson of Kentucky, who is a critic of the court, and he's proposing a number of constitutional amendments to clip its wings.

You can feel the urgency of this crisis, of this issue in in Marshall's handwriting.

He's not in the letter.

Marshall opposes Senator Johnson's constitutional amendments on the grounds that they would weaken the very authority Marshall himself had worked so hard to establish for the court.

His recipient here is Henry Clay, who's another senator, sympathetic senator.

Yeah.

So he's writing, an ally in the Senate about an enemy in the sun.

How often did Marshall intervene or try to connect with the political sphere as he was preserving the court's autonomy very carefully and very strategically?

John Marshall is now, in his mid 60s, one of the most eminent men in the land.

But home in Richmond, away from Washington and Supreme Court responsibilities, is still the same.

Down to earth man who enjoys family games and drinking with friends and neighbors.

Every Saturday from May to October, Marshall would walk to a nearby farm, now this Richmond City Park, and play quoits, an old British game like horseshoes but played with metal rings.

Oh, there's it's touching the Lehner.

It in contested throws.

You find the Chief Justice of the United States.

He's down on all fours with a straw, measuring the distance of the court from the pay.

Another point.

All right, let's have a count.

13.

Oh, Marshall.

Love this.

He had a few, mint juleps along the way, which he was famous for.

Well, Marshall would just come up and stick his mug right in the thing.

That's right.

And say, hello, gentlemen.

And you couldn't talk about politics or religion, in which case you got fined.

And let's define a case of champagne.

It's a champagne story, said I love his laugh.

That's right.

Love letter to Hardy for an injury for entregar.

I mean, I don't have that many descriptions of people's laughs.

Oh, no, but that was Marshall's way, wasn't it, to bring people together that had different views, to talk it out in a, you know, informal setting?

His whether it was at his dinner table or over a quaint game or at the Supreme Court.

Marshall's 1812 attempts to survey a canal route from Virginia to the Ohio may not have succeeded, but as the American frontier pushes west and trade with the East becomes a national priority, technological change fuels an infrastructure frenzy.

Speculators are building roads and digging canals, and waterway traffic will be the next case before Marshall's Court to pit federal power against states rights.

For centuries, ships depended on wind and sails for power.

But when Robert Fulton figured out how to attach a steam engine to a paddle wheel, everything changed.

Holton was the inventor of the steamboat, and Livingston was his financial backer.

New York gave them a charter that said they would have exclusive rights to ferry passengers up the Hudson, down the Hudson to ports of New York.

There was a fear that if there was too much competition, it wouldn't be lucrative and people would stop investing in steamboats.

Robert Fulton tragically passes away, but his license lives on, and Ogden is the inheritor of his license to New York in the 1820s is the nation's financial and economic heart.

Its politicians and entrepreneurs are aggressive in their efforts to keep it that way.

Thomas Gibbons is a new competitor, and he wants to run, boats between New York and New Jersey across the Hudson River.

Gibbons insisted that this monopoly was not only unwise economically, but it was unconstitutional, Gibbons says.

You can't have a monopoly on navigation from one state to another.

That's that's interfering with interstate commerce.

The number one question is, is navigation within the commerce power, which says Congress shall have power, to regulate commerce with foreign nations among the several states and with Indian tribes.

It is the end of a long period of stability for the Marshall Court.

Justice Brockholes Livingston has died the previous year, but his replacement, Justice Smith Thompson, will miss the start of the 1824 session.

So Gibbons versus Ogden is heard by the six justices who have now been together for 12 years.

Lawyers for Air and Ogden agree that state regulations cannot trump laws of Congress, but insist that Congress has passed no laws regulating steamboats, so their monopoly simply fills a vacuum.

Gibbons hires Daniel Webster, now a leading congressman and chair of the House Judiciary Committee, to argue his case before the Supreme Court.

Daniel Webster argued for national power.

Even if it's not narrowly buying and selling, it's not commerce in the most narrow imaginable sense, Congress has the power to regulate all sorts of things that involve more states than one commerce power, which is one of the most important powers ever granted to the federal government, had never been interpreted by the court or any court until 1824.

Marshall's opinion, and Gibbons versus Ogden will be another forceful declaration of federal supremacy.

The United States basically is almost entirely composed of states, so you're always going to be in one state or another state.

But when you're trying to get from one state to another state, the entity that should be able to regulate that transaction is an entity where those states are both represented.

And that's Congress.

Steamboats may be licensed in common with vessels using sails.

The laws of Congress do not look to the principle by which the vessels are moved.

Any law of the State of New York upholding the monopoly is repugnant to the Constitution, and void when it actually came down to the interpretation of the Constitution.

I don't think he ever very he ever wavered from what he believed the Constitution really meant.

And he had strong ideas about that.

He was close enough to the founding era to have a feeling that he understood the essence of the Constitution.

Now, whether Marshall intended to authorize such a broad, capacious power is an open question.

It's undermined by the fact that in the in Gibbons he also identifies what the broad powers of states are, which includes the regulation that, you know, health and welfare laws of every description.

New York's law was unconstitutional because of the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution.

Supremacy clause says that federal law prevails over state law where they are in conflict with one another.

Federal law has to prevail.

Within a year of Marshall's decision, the number of steamships using New York's harbors grows by 700%, while trade and passenger traffic on America's waterways expands exponentially.

Marshall and the other Federalists believed that we needed a flourishing national economy for the nation to flourish as a commercial republic is the sort of thing Hamilton, the great arch federalist envisioned.

And he viewed the Constitution as, essential to preserve, I think his vision of what the country was going to be like his Federalist, view of how the country should, should function.

This is the last great nationalist opinion of Marshall, because the forces of states rights opposition are ardent, are gathering.

And in the mid 1820s, in a very serious way.

And slavery is one of the biggest issues around which states rights are focused.

Slavery is the ever present and ever invisible issue.

It's everywhere.

Men like Adams were anti-slavery.

Hamilton was anti-slavery.

Jefferson knew it was wrong, but he practiced it.

The nation is built on slavery.

However, no one wants to talk about it in the realms of the national government because it is literally a deal breaker of one sort or another.

The Constitution does not mention the word slavery.

At the same time, there were a series of fatally significant compromises over the slave trade in order to maintain unity so that republican government could prevail.

Despite the differences about slavery.

The framers made the compromises they did with slavery because they realized that no constitution could be ratified without.

Some states wanted to ban the importation of slaves, others wanted to preserve the slave trade.

The compromise was to allow Congress to ban the importation of slaves, but only after 1808.

After 1808, the slave trade was legal in the United States, supposedly illegal, and obviously there were, illegal shipments of people.

But in this period, the nation is expanding, and as it expands, every new state raises the issue.

Is this going to be a state where slavery is allowed or not?

The Missouri Compromise was made in 1820, with Missouri admitted to the Union as a slave state, while Maine comes in as a free state, maintaining the balance of power in the Senate between North and South, and in 1819, Congress passed a new law that heightened penalties that provided funds for the enforcement of the prohibition on the slave trade.

Now, when slave ships carrying illegal cargoes were captured, those potentially enslaved people would be turned over to the federal government, and they would be then returned to Africa.

One ship, antelope, becomes a symbol of the international traffic and human flesh.

An 1820 antelope is a Spanish ship buying slaves on the coast of Africa.

It's captured by a competitor, a South American privateer that had already plundered American and Portuguese slave ships.

Antelope and its captor had back across the Atlantic to sell their human cargo.

When the privateer wrecks and the storm.

Antelope sails on.

I'm on the Savannah River and Georgia with the U.S.

Coast Guard.

It was from here that the Revenue Cutter Service, as the Coast Guard was then known, first gets word that a slave ship is approaching American shores.

The antelope is coming up through the Caribbean, trying to work its way up to where it can illegally sell the enslaved persons on board.

They really were limited to coming up to Florida.

The border between Florida and Georgia, try to meet up with smugglers to get them in through their word had gone up to Savannah at Saint Mary's.

There's a pirate down there.

They had reports that a slave ship was there.

Other mariners had seen him.

There's unmistakable.

He got close enough to talk.

You knew there were slaves on board.

Captain Jackson asked for reinforcements because he knows that a ship like the antelope was engaged in nefarious purposes, ready to cut off, pursues, gets upwind of them, which is called having the weather gauge on them, and gradually closes to within about half a pistol shot.

It turns out the new captain and most of its crew are American, but they claim they are not pirates.

But privateers legally sailing for a revolutionary South American government.

But American law is clear.

If you're headed to the United States with illegal slaves, it doesn't matter where the Coast Guard vessel finds you.

So this is a well, we're going to season this and arrest you, and we'll let the lawyers argue about it when we get in.

Antelopes.

Human cargo seized from American, Portuguese and Spanish ships creates a legal tangle that will keep their fate undecided for more than five years.

Now, once they get to Savannah, they're turned over the custody of the U.S.

Marshal.

That's an important distinction there.

They want to keep them under federal custody as they go into state custody, the tendency for them to disappear, there would be a bond put on them, and they would never be returned.

The bond would be forfeit.

But it was cheaper than buying additional people.

The Africans had been brought to a country which forbade the slave trade, but where half the states practiced slavery, what would become of them?

Ultimately, the courts would decide.

I've come to the Owens Thomas Mansion in Savannah, built by one of Savannah's major slave owners, to meet Jonathan Bryant, an expert on the antelope.

So this looks like, the kind of house that Marshall lived in, Marshall socialized in.

And Richmond.

Yes.

He would have moved in circles similar to the builder of this house.

Richard Richardson was a very active slave trader and quite wealthy.

The antelope case, after it finally reaches the Supreme Court in 1825, raises hard questions about Marshall's motives in deciding slavery cases that come before his court.

So Marshall, as a slave owner all his life, how do we think that impacts his jurisprudence?

It is a difficult question.

My guess is that Marshall would have been in the top 10%, if not higher of all Virginia slaveholders.

It makes him sympathetic to the slave owner, not the slave.

Marshall was a slave owner.

And yet he was also a founding member of the American Colonization Society.

And the American Colonization Society was of the view that slavery should be ended in the United States, but that African American people should be sent back to Africa.

Marshall was a part of the American Colonization Society because he believed that emancipation should come, but that blacks could not stay in the United States.

America was not going to be a multiracial society.

These were questions for the future.

The immediate issue is what to do with all the slaves from the antelope?

A probably there were 331 captives who left Africa when they were captured by the revenue cutter.

They were either 280 or 281 still alive, whether from yellow fever or from problems brought with them, aboard the ship.

The captives continued dying.

So we're going from the big house to the slave quarters.

Yes.

And, the U.S.

marshal was in charge of these captives, and he decided to distribute them to wealthy families here in town.

Slavers in an urban situation.

These are the actual slave quarters.

There were probably between 7 and 9 enslaved servants, who lived here.

Many of the antelope Africans were sent to urban houses because of their use, right?

That's correct.

The antelope captives were quite young.

On average under 14.

And so large numbers of them were placed with families here in Savannah.

Very often you would, as a child, work in a household in the city.

And then as you became older and stronger, you would be moved to a plantation to do farm labor.

It will take years for the case to work its way up to the lower courts as multiple claimants assert ownership, including Spain, Portugal and the antelopes.

Captive.

Whose slaves were these?

Whose ship was this?

If this was an American ship, really?

If these slaves belonged to an American owner, then they would be released and returned to Africa.

If, however, these slaves belonged to Portugal or Spain, Portugal and Spain were legally engaged in the slave trade, and they would presumptively be entitled to the return of these slaves to their owners or to their government.

If the owners couldn't be identified, 40 slaves would make you a millionaire many times over.

In those days, it's an enormous amount of wealth.

By the time they're making this decision in February of 1821, there are only 212 of the captives left alive while they're deciding this.

Richard W Habersham, the United States attorney here in Savannah suddenly entered the case and to everyone's surprise, announced that, no, these people are free and they should be returned to Africa.

And this was startling in Savannah.

Savannah.

And I assumed that everyone would get to divvy up these captives as slaves and make a little money out of this.

The federal district judge dismisses the claim of antelopes captain, but accepts those of Spain and Portugal.

And Habersham says, I'm appealing this to the Federal Circuit Court martial.

Supreme court colleague William Johnson is the circuit judge.

While upholding the lower court's decision, Johnson rules that African seaboard antelope previously captured from an American vessel were enslaved illegally and must be free, and he also rules that who goes to the United States for freedom, who goes to the Portuguese and who goes to the Spanish will all be decided by a lottery.

How do you know which of the 2 or 300 slaves are free?

Put your slave.

I mean, just stop and figure.

I mean, human beings trade freedom descended by, you know, who draws a piece of paper out of the hat?

Habersham literally leaps up and he is outraged, and he announces that he's going to appeal this to the United States Supreme Court for the antelope case, brought Marshall and the court head to head.