Finding Your Roots

Family Harmonies

Season 12 Episode 7 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

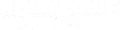

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. introduces musicians Flea and Lizzo to their inspiring ancestors.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the roots of two celebrated musicians: Lizzo and Flea, tracing lineages that run from plantations in the American South to battlefields in France to a hardscrabble gold mining town on the shores of Australia. Along the way, Lizzo and Flea reimagine themselves as they learn the true stories of the people who laid the groundwork for their success—and inspired their art.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Family Harmonies

Season 12 Episode 7 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the roots of two celebrated musicians: Lizzo and Flea, tracing lineages that run from plantations in the American South to battlefields in France to a hardscrabble gold mining town on the shores of Australia. Along the way, Lizzo and Flea reimagine themselves as they learn the true stories of the people who laid the groundwork for their success—and inspired their art.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

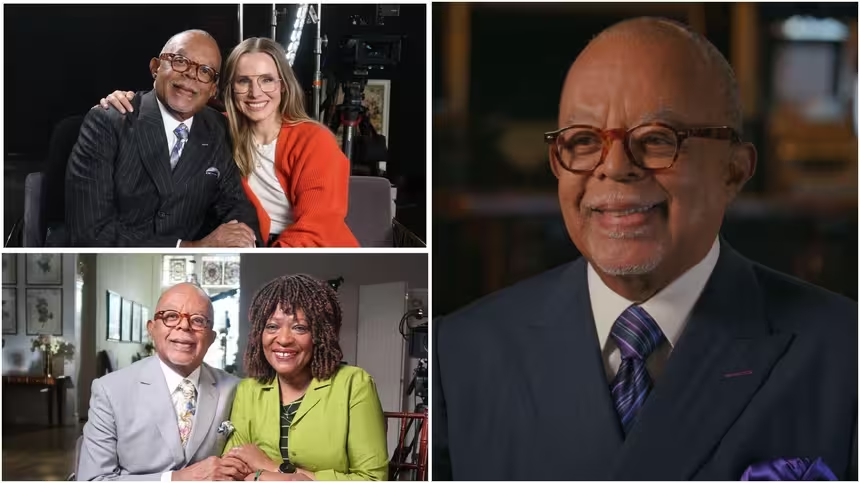

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet Lizzo and Flea, two extraordinary musicians whose lives were transformed by their talents.

LIZZO: I was weird.

I stood out 'cause I would write raps all the time, like when I was like 10 or 11 or 12, and I would always like subvert expectations.

FLEA: Growing up, I thought that I was never good enough, that the world was scary.

But as soon as I discovered music, I thought, this is what real is.

This is something to hold onto.

And it just took over my life.

All of a sudden, I was interesting, instead of weird.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

LIZZO: That's crazy.

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

FLEA: Wow.

GATES: And we've compiled everything... FLEA: Wow.

GATES: Into a "Book of Life."

LIZZO: Oh my gosh.

GATES: A record of all of our discoveries.

FLEA: How the hell did you find this?

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

LIZZO: You just think about like the little things that have to happen for you to exist.

GATES: That's right.

LIZZO: I'm actually speechless by that.

FLEA: I don't know why this has affected me so much.

It's emotional, someone I never knew, you know, you just feel like you know him a little bit.

It's family.

GATES: My two guests have performed all over the world, bringing joy to generations of listeners.

In this episode, they'll step off the stage and become listeners themselves, hearing stories about long-lost ancestors, stories that will forever change how they understand who they are.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ LIZZO: It ain't my fault ♪ ♪ that I'm out here gettin' loose, ♪ ♪ gotta blame it on the goose... ♪ GATES: Lizzo is a force of nature.

The Grammy award-winning singer radiates an infectious charisma.

And her message of female empowerment has proven both widely resonant and wildly entertaining.

♪ LIZZO: Blame it on my juice, ♪ ♪ blame it, blame it on my juice.

♪ GATES: Watching her perform, it seems Lizzo was destined for the stage.

And in a sense, she was.

Born Melissa Jefferson, Lizzo, was raised in Houston, Texas, in a churchgoing family filled with talented musicians.

And she grew up wanting to join them.

LIZZO: I knew when I was nine years old.

GATES: You did?

LIZZO: It's so wild.

I knew I wanted to be like the Spice Girls so bad, and I wanted to be like Destiny's Child.

And I was put, I was forming little girl groups, and my first girl group was Peace, Love, and Joy.

And I was like, "You be, you be 'Love,' you be 'Joy,' I'll be 'Peace,' that's our brand."

And I was writing these little girl power songs.

GATES: Yeah?

LIZZO: Yeah.

And then I had another girl group, Initials, and then I had another girl group, and then I had Cornrow Clique.

And so I was always a part of these girl groups, 'cause, but I, I, I wanted to be a part of a team.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: Really badly.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: A girl team.

GATES: Lizzo's ambitions may have been clear, but she struggled mightily to make them a reality.

After high school, she became the lead singer of an experimental rock band and started playing small clubs in Houston.

But her world was turned upside down when her father passed away, just before her 21st birthday, leaving Lizzo utterly shattered.

LIZZO: It got really bad.

I stopped going to work, I stopped paying my car note, stopped paying rent.

Actually, my car just disappeared.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: 'Cause I didn't, I think it got repo'd.

GATES: Uh-huh.

LIZZO: And I remember being like, "Oh, well."

And I was homeless for a year.

GATES: Oh, poor baby.

LIZZO: I was showering at the gym.

I was sneaking into the gym to use the showers.

GATES: Oh.

LIZZO: Yeah.

Friends were feeding me.

GATES: You descended into the valley of the shadow... LIZZO: Yeah.

GATES: ....in the wake of your father's death.

LIZZO: Yeah.

GATES: Mm.

LIZZO: It was rough.

And my mom, you know, I know she feels bad 'cause she'd be like, "Please just come home."

Like, you can just come home.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: But it was so hard.

I remember, I, I remember in the dark, and I was laying there, I was thinking, and I was like, "Why is everything so hard?"

I was like, is this like God trying to warn me to get outta this situation?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: Or is this God trying to make me stronger?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: By enduring this situation.

I didn't know.

GATES: Lizzo's questions would soon be answered.

In 2011, she moved to Minneapolis, drawn by the city's vibrant music scene, and ended up in a girl group called The Chalice, with a sound that was more in line with her talents.

The group's success would attract the attention of one of Lizzo's idols, Prince, and Prince gave her the chance to turn her life around.

LIZZO: He was like, "I want you to be on this song."

And he had us in the studio, played the song, and he was like, you know, "It's your song.

Just pretend it's your song."

And I went so crazy on that song, boy.

I said, I'm gonna rap, I'm gonna sing, I'm going squall, I'm going to give it to you.

And I did... GATES: Uh-huh.

LIZZO: And he was like, I can offer you the world, you know what I mean?

And was like, "But you can't cuss, you can't talk about anything negative."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: And I remember being like, "Huh, no cussing, no negativity."

And that became the catalyst of me making positive music.

GATES: Hmm.

LIZZO: I started, 'cause I used to talk about like, uh, I'm anxious, I'm broke, I'm tired.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: I'm, uh, it was always this negative stuff.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: And I remember being like, my mom being like, "If you gonna talk about being broke and tired, you're gonna be broke and tired."

And I was like, "Yeah, whatever, Mom."

GATES: I like your mom.

LIZZO: Right.

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: So I, I tried to start talking about more positive things, but it was really ego-based.

But then once it was like, no, don't cuss, don't talk about nothing negative.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: I started making positive music, and that's how I got to where I am today.

GATES: My second guest is Michael Balzary, better known as Flea.

The legendary bassist of The Red Hot Chili Peppers, one of the most successful rock bands of all time.

Over the last four decades, Flea and his band have packed stadiums around the world and sold more than 120 million records.

But the man who was brought so much joy to so many people came to his calling almost by accident.

Flea was born in Australia and might never have found music at all, were it not for his parents' troubled marriage.

FLEA: My real father, my biological father, you know, had a suit, briefcase, went to work every day.

Uh, he worked when we moved to New York when I was four; he worked at the Australian Consulate as a government official of some kind.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Customs, I think he did.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Um, I never quite understood what he did.

Um, and, and my mom left him, remarried when I was seven years old, and, uh, to a jazz musician.

And he started having other jazz musicians come over for jam sessions.

GATES: Wow.

FLEA: And they'd all set up in the living room and play, you know, we'd have food, everyone would be drinking, smoking weed, playing Bebop, you know, and these guys are just going for it.

You know... (imitating jazz musicians).

You know, Bebop.

GATES: That's Bebop, that's Bebop.

FLEA: Very cerebral, very sophisticated, very emotional, spiritual, physical music.

GATES: Right.

FLEA: And, um, the first time I saw it, if you would like, disappear right now, or start walking on air, or turn, turn into a, a pig... GATES: Uh-huh.

FLEA: It wouldn't be any more amazing than how that made me feel when I was a child.

I remember just, you know, rolling around on the floor laughing, 'cause I was so overwhelmed with joy.

GATES: The joy of that moment would soon lead Flea to take up the trumpet, but it would also lead to something much darker.

In 1972, when Flea was nine years old, he moved yet again, this time to Los Angeles, where his stepfather attempted to launch a music career and ended up in the throes of addiction, casting Flea's family into chaos.

FLEA: It was terrifying to be in our house.

I used to, um, sleep in the backyard out in the garage.

GATES: Mm.

FLEA: It was too scary to be in the house.

He was, um, you know, he was, uh, emotionally very unstable and violent and, um, would destroy the entire house.

And, you know, my mom would leave him.

We'd always go back.

We'd run and go stay in a motel somewhere, and then come back.

The police would take him away.

I'd come home, and it'd be cops outside with guns.

You know, it was just scary, 'cause you didn't know when it was gonna happen, what was gonna happen next.

GATES: Mm.

FLEA: You know, and so when I was 12 years old, I'd be out to three in the morning, four in the morning, out on Hollywood Boulevard, you know, running around, stealing stuff.

GATES: Mm.

FLEA: I started getting high when I was about 11, I started smoking pot.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Um, and as my teenage years went on at, got into all the hard drugs and all that.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Um, and at the time, it's funny, I didn't think of it as quelling pain... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: ...'cause I didn't know what it was to not be in pain.

GATES: Fortunately, Flea would find other ways to handle pain.

And he's been drug-free for decades.

But his path to happiness began on the same streets where he tried to lose himself, in a chance encounter with a kindred spirit.

A classmate named Hillel Slovak.

Hillel went on to become a fellow founding member of The Red Hot Chili Peppers.

A guiding light in Flea's life.

FLEA: We met him while we were hitchhiking one day in the street, and he drove by and picked us up and... (laughter).

GATES: And that was it.

FLEA: Uh, yeah.

And, and we just kind of became inseparable.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: And one day he was like, you know, our bass player, he is just not serious.

He doesn't, he doesn't believe in it and, and why don't you learn how to play the bass?

And I was so happy, I, I couldn't believe... GATES: Huh, why?

FLEA: ...that he asked me.

Um, I think I always felt kind of like an outcast.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: And like, I didn't belong.

I always felt kind of removed from what I saw as like, the center of what was happening in school and social, I was just kind of a outcast.

That's how I felt.

And, um, he asked me to be a part of something.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: And I went out and got a bass the next day.

I think my friend's dad had an extra bass, let me use it until I could figure out getting one on my own.

And, um, literally two weeks later, I was on stage on at a nightclub on Sunset Boulevard... GATES: No.

FLEA: ...performing.

GATES: Wow.

FLEA: Two weeks from the day I started.

GATES: That's amazing.

FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: That is amazing.

FLEA: You know, acting like a rock star, posing and prancing around, and that changed my life forever.

GATES: My two guests found fame when they were young, and they've never let it go.

But living in the limelight means living far from your roots.

And both came to me with fundamental questions about those roots.

It was time to provide some answers.

I started with Lizzo and with a mystery at the heart of her family tree.

Lizzo's father, Michael, grew up knowing little about his own father, Lizzo's grandfather, a man named John Andrew Franklin.

What have you heard about him?

LIZZO: The only thing I've heard is we don't know his ethnicity.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: We don't know who his parents are.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: There's a story that he's Puerto Rican; there's a story that he's White.

There's a story that he's super light-skinned.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: We don't know.

GATES: Okay, you ready to find out?

LIZZO: Yes.

GATES: Please turn the page.

LIZZO: This is crazy.

GATES: This is your grandfather's application for Social Security.

It's dated February 10th, 1940.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

LIZZO: "John Andrew Franklin, age 18.

Mother's full of name Hattie Caldonia Cunningham."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: "Father's name Calvin Columbus Franklin."

GATES: Have you ever heard those names?

LIZZO: Never heard those names.

GATES: Now that we knew their names, we set out to learn more about Lizzo's great-grandparents, and we soon encountered something puzzling.

In the 1930 census for Muldon, Mississippi, we found Lizzo's great-grandmother, Hattie.

She's listed as being Black and single, and she's raising seven children, including John, all on her own.

So why wasn't John's father Calvin with the family?

His death certificate, filed in Memphis, Tennessee, over a decade later, contains a clue.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

LIZZO: "Certificate of Death: Full name Calvin Columbus Franklin.

Race or color?

White."

There it is.

GATES: There it is.

Your great-grandfather was a White man.

LIZZO: Whoa.

GATES: How does that make you feel?

LIZZO: I, I just wanna know what, what happened between them, what's the story?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: You know, you hear about things like that back then, and you assume something negative, you know?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: You don't assume it was outta love, you know?

And I hate that that's where my mind went to something like rape or, you know what I mean?

GATES: But your grandfather knew the name of his father.

LIZZO: He knew the name.

GATES: If you had a child as, after you were raped, I, it's difficult for me to imagine, your gonna tell... LIZZO: That's true.

GATES: ...your child, the name of your rapist.

LIZZO: What's their story then?

GATES: We don't know what exactly happened between Hattie and Calvin; there are no records to tell us.

But Calvin's obituary, published in Memphis on December 31st, 1943, shows that he was a man of many secrets.

LIZZO: "Mr.

Franklin was born in Muldon, Mississippi.

He leaves his wife, Mrs.

Virgie McConnell Franklin of Memphis..." Wow, look at this.

"Two daughters, Mrs.

Russell.

J Hennessey."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: "And Mrs.

Winston Jackson.

Both from Memphis, six sons: C.O.

and J.C.

Franklin of Memphis, J.B.

and C.E.

Franklin of Jackson, Mississippi.

Staff Sergeant Thomas J. Franklin of the Marine Corps and Private Claude J. Franklin of the Army."

GATES: There's your great-grandfather.

According to this obituary, at the time of his death, he was a married man.

LIZZO: Hmm.

GATES: Married to a White woman and they had eight children, two daughters and six sons.

Those children are your grandfather John's, White half-siblings.

LIZZO: Wow.

GATES: John himself, of course, was omitted from the obituary.

LIZZO: Right.

GATES: So he had an affair with your great-grandmother.

LIZZO: Right, right.

GATES: Do you think Calvin's wife and children knew that they had a mixed-race, half-sibling?

Probably... LIZZO: Probably not.

GATES: Yeah.

But we know from the documents we gathered that your grandfather knew who his father was.

LIZZO: Yes.

GATES: We also know from this obituary that Calvin moved away from Muldon to Memphis in 1922, the very year your grandfather was born.

LIZZO: Oh, scandaloso.

GATES: We can't be certain that Calvin's move was the result of John's birth, but it seems highly likely.

And as we dug deeper, we noticed something that shed a little more light on the relationship between Lizzo's great-grandparents.

The 1920 census for Mississippi recorded about two years before John was born, shows that Calvin and Hattie lived just a short distance apart and that Calvin was already married at the time.

So he was cheating on his wife.

LIZZO: Ah.

GATES: We don't know if any of John Andrew's siblings were also fathered by Calvin.

LIZZO: Right.

GATES: We don't know.

We found an online obit that refers to Calvin as the father of John's older sister, Evelyn.

LIZZO: Stop.

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: So multiple kids.

GATES: That's from the obituary, which have been, you know, somebody in the family has to put down who was the father and who was mother.

LIZZO: Right, and she had seven kids.

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: Two of them.

GATES: So if there were two, that means they had a relationship.

LIZZO: That's a relationship.

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: That's a situationship.

GATES: Please turn the page.

LIZZO: Oh, who is that?

GATES: That is your great-grandfather.

LIZZO: That's Calvin.

GATES: That is Calvin Columbus Franklin.

That is your father's grandfather.

LIZZO: He had blue eyes.

Oh my gosh.

Oh my gosh.

I've had like, you know, like a... (makes sound).

Like spidey sense, like my whole body, like... (makes screeching sound).

...when I saw him.

(laughter).

Wow.

This is wild.

This is crazy.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

LIZZO: Okay, alright, now that I've gotten over the White man of it all... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: His energy, he gives, like, I can see, I can see he's got like a puppy dog eyes type of thing.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: And I can see... GATES: Why she would fall for him?

LIZZO: Why she would like him.

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: He got the suit on, down.

This is wild.

This is so wild.

GATES: Unfortunately, this story was about to take a painful turn, digging into Calvin's roots.

We discovered that Lizzo's White family traces back to the 1700s through Mississippi and South Carolina, and includes at least three men who own slaves.

Leaving Lizzo to puzzle over this very complicated newly found branch of her family tree.

LIZZO: I have a lot to process... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: ...with the White side.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: Um, but I don't feel like there's that much White side.

It's just a little, it's a little, but I got way more Black side.

(laughter).

But, um... GATES: Did, when you were growing up, did anybody ever get on you?

"You think you White, you act White?"

LIZZO: Oh yeah, I got that a lot.

GATES: Well, see, they were right.

LIZZO: Ah, don't play with me.

That is true.

All the White-girl allegations are true, honey.

Yeah, it's, it's, you know.

GATES: How much resolution would this have brought to your father to know?

How would he be feeling right now?

LIZZO: I think that he would have, um, gotten a good laugh out of, uh, this one right here.

He look; he look apologetic.

He look like, "I'm sorry."

Yeah, you should be.

GATES: Like Lizzo, Flea grew up knowing little about his paternal roots, but for very different reasons.

His father, a man named Noel Balzary, moved back to Australia when Flea was eight years old.

And the two had a distant, often strained relationship for decades, in no small part due to Noel's struggles with alcohol.

And although they were at peace by the end of Noel's life, Flea still wrestles with his father's memory.

What do you miss most about him?

FLEA: You know, I miss, I always kind of hoped that our relationship could be better and deeper and, um, I miss kind of just the hope that it could be what it could be.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: You know, and I think when he died, one of the things that was really hard for me was that it didn't get to what I always kind of my dream relationship with him, you know, the sense of ease and comfort and, uh, humor and you know, the things that you want when you spend time with someone.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: But he was such a strange character of a man.

Um, yeah.

And I, I, yeah, he was, he was funny and nutty and, um, and when you get him in the right time, you know, my father really drank a lot, so you'd have to kind of catch him in the right moment, you know, how it is with alcohol, you know, kind of on way up or, um, he would, he, he'd be, you know, really funny and charming, you know?

I miss that, yeah.

GATES: Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the gaps between them, Flea and Noel rarely discussed their shared roots.

Flea knew that Noel's father, Clifford Vincent Balzary, had also battled alcoholism.

And he'd heard that Clifford had been a difficult man.

But when we began to research Clifford's life, we found that a crucial part of his story had not been passed down.

It begins in Australia's national archives with the World War I enlistment record.

FLEA: "To the recruiting officer at Melbourne.

I, Clifford Vincent Balzary, hereby offer myself for enlistment in the Australian Imperial Force for active service abroad.

Consent of parents or guardians for persons under 21, father's signature, Edwin A. Balzary, mother's signature, Ehmma Balzary."

How the hell did you find this?

(laughter).

GATES: I take it you've never seen this?

FLEA: No.

GATES: Clifford enlisted in March, 1917.

He was just 18 years old.

Now, what were you doing when you were 18 years old?

FLEA: Smoking weed, hanging out at the park.

(laughter).

Yeah.

GATES: What's it like to learn, uh, that your ancestor at that age did this?

FLEA: It's intense and very much like my father to do that.

Um, you do your duty.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: No matter what.

My father really believed it.

And my father was also very like, nationalistic, like, Australia Day was a big day, you know, he is very patriotic in that way.

GATES: Uh-huh.

FLEA: And, um, you know, we've always gone with America.

We've always gone with, you know, with England, you know, you don't question these things.

These are the alliances that make us who we are.

He really believed in that.

Um, and it very much makes sense.

I mean, yeah.

It adds up in my mind that that's something that my father's father would've done.

GATES: As it turns out, Clifford was not the only person in his family who was eager to serve his country.

Records showed that his older brother, a man named Leonard Balzary, had enlisted two years before him.

FLEA: So I have a great uncle named Leonard?

GATES: There you go.

FLEA: Wow.

GATES: He enlisted in July 1915 when he was 18 years old, two years before your grandfather.

And you've heard nothing about this?

FLEA: No.

GATES: What's it like to learn that you're related to not one, but two Balzarys who fought in World War I?

FLEA: Um, it's amazing to know, you know, uh, it, it can't help but like open up in my imagination, like what was it like for them?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: They had been in Australia, like living a very provincial, rural type of life, I'm sure... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Um, in Australia at that time, and they got on a ship, where did they go?

GATES: Right.

FLEA: Did they go all the way to Europe?

You know, wow.

GATES: The two brothers would indeed find themselves in Europe, but not in a way that either of them likely hoped or imagined.

When Clifford enlisted, Leonard was already in France serving on the infamous Western Front.

Months later, Flea's grandfather would board a transport ship seemingly bound to follow in his brother's footsteps.

But by the time Clifford arrived, Leonard had made the ultimate sacrifice.

FLEA: "Casualty was sitting on the side of Westhoek Ridge in the open, a shrapnel shell exploded near casualty, killing him instantly, and went immediately to his assistance, but he was beyond all aid.

He was buried near Westhoek Ridge, but I do not know the exact spot."

So that's my Uncle Leonard.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: My great uncle Leonard.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: He got killed.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: Wow.

GATES: He was 20 years old, Flea.

FLEA: Oh man.

GATES: What's it like to learn that?

FLEA: I mean, I'm grateful for it; it's unbelievable that you unearthed this.

I don't know how you guys find this stuff.

Um, yeah, I'm... crazy man.

It's, it's, uh, it's emotional, someone I never knew, you know, and just reading the first part, made me... you just feel like you know him a little bit all of a sudden, you know?

GATES: Sure.

FLEA: It's family.

GATES: Leonard died in September 1917 near Ypres, Belgium.

He was buried in an unmarked grave near where he fell.

Less than a year later, his brother Clifford would arrive in the same place, heading into a nightmare.

(explosions).

In August of 1918, Clifford's division joined other allied forces in what became known as the Hundred Days Offensive, an all-out effort to break through Germany's trenches and end the war.

The offensive would prove a success, but it came at an enormous cost.

It's estimated that the allies suffered over one million casualties, including more than 25,000 Australians, some of whom Clifford likely knew.

So how do you think it affected him?

FLEA: Without doubt, like, you don't come home the same.

GATES: No, you can't come back normal or the way that you left.

FLEA: No.

GATES: Plus your brother's dead.

FLEA: Yeah, no, your relationship to life and to what human beings are capable, capable of changes forever.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: From what I know from my dad, he drank a real lot.

GATES: Mm.

FLEA: And that it killed him at a, you know, he didn't live long.

GATES: Mm.

FLEA: And you know, per, perhaps the trauma of that, he must have seen a lot of, you know, people being blown up and killed and stabbed and shot and bayonetted and whatever they did.

Maybe that's, you know, a birth of a lot of trauma, you know, that, you know, back then, I don't think you got, um, you know, I've got stress disorder after the war, or whatever it is, you know.

GATES: No, PTSD didn't exist as a concept.

FLEA: Yeah.

Get over it.

GATES: Yeah, be a man.

FLEA: You know, especially in Australian culture.

GATES: Oh yeah?

FLEA: Yeah, there's none of that.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: No coddling.

GATES: Clifford was honorably discharged on October 2nd, 1919, more than two and a half years after enlisting.

He was just 20 years old and had survived some of the worst combat in the history of war.

He would eventually receive multiple medals for his service, but it's not at all clear that he ever recovered from the stress.

Do you think your father knew any of this?

FLEA: He must have.

He must have.

And he might have, like, I, I feel dopey, like he might've like dropped a little bit here of it here and there, and I didn't really get it.

GATES: Uh-huh.

FLEA: You know.

GATES: Uh-huh.

FLEA: I'm wondering, like what, anything that he said that I missed.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: You know?

Um... GATES: Or maybe he didn't want to talk about it.

FLEA: It could be, yeah.

GATES: You know?

FLEA: It was too painful to him to talk about or... GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: I just don't know.

I just, there's so much all unknown to me.

GATES: Uh-huh, has it changed anything about the way you now think of your father?

FLEA: Um, it makes me understand him better.

Doesn't really change my opinion of him or, you know, what kind of man he was, it makes me understand more.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Like, you talk about trauma being handed down, and I think about how much, like, my sister and I were often kind of angry with him... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Over what we saw as, you know, dysfunctional behavior and anger and trauma, and like how much he was doing the best that he could with what he had.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: And what was handed down to him.

GATES: We'd already traced Lizzo's paternal roots back two generations in the Jim Crow South.

Now, Lizzo was hoping we could go further back into the slave era.

In the archives of Mississippi, we found Lizzo's fourth great-grandparents, a couple named Ambrose and Susan Dangerfield, as well as their daughter, Susan.

They're all listed as property in the estate records of the White man who owned them.

LIZZO: "Chattels and personal estate of Nathaniel H. Hugh, and Noxubee County deceased.

Ambrose valued at 600.

Susan valued at 200.

Susan valued at 325."

Chattels is crazy.

GATES: Mm.

LIZZO: $200.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

To see your own flesh and blood listed as property with a value put next to their names?

LIZZO: I think there's a certain gravity that you feel, because we as Black people today are far removed from chattel slavery.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: Just from, just because of time.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: But also the erasure that's starting to happen, um, in our schools where they don't teach it anymore, it's starting to be suggested, it's starting to be like, "Oh, they were indentured servants."

"They were..." GATES: Right.

LIZZO: "They were immigrants."

GATES: Right.

LIZZO: No, they were stolen.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: Um, seeing something like this makes it, it brings me right there.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: It like closes the gap... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: ...between 1865 and today.

GATES: Right.

LIZZO: And it's like, it's heavy.

GATES: Mm.

LIZZO: It's very heavy.

GATES: This story was about to take an unexpected turn.

Lizzo's ancestors were enslaved by a man named Nathaniel Hugh.

He owned vast plantations in both Mississippi and Virginia and kept hundreds of people in bondage.

But when he died, his will suggests that he was not exactly a typical slave owner.

LIZZO: Whoa.

"Tenth item, 'I emancipate and set free my slaves in Virginia and set those free to be sent to Africa by my executors and their expenses paid out of any monies under their control.

I do also emancipate and set free each and every one of my slaves in the state of Mississippi now under the control and management of Matthias Mahorner in Noxubee County as above directed before starting for Africa.'"

Huh, plot twist.

(laughter).

He emancipated them.

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: And paid for their trip back to Africa?

GATES: That's what he said in his will, when I die, I have left money, and this has to happen.

(laughter).

Nathaniel Hugh passed away in 1844, and the unusual stipulation in his will would prove fodder for the local press, which detailed his involvement with what was known as the American Colonization Society.

A group founded to promote the emancipation of enslaved people and their resettlement in Liberia, a colony the society had founded on the Pepper Coast of Africa.

LIZZO: "Mr.

Nathaniel H. Hugh of King George County, lately deceased, left by his will nearly all his slaves, free, amounting to some two or 300 slaves."

GATES: Yeah.

LIZZO: "With ample provision to carry them to Liberia.

The liberated slaves are to be removed under the direction of the Colonization Society."

GATES: We have never seen anything like this in the whole history of this show, never.

And I've read about the American Colonization Society since I was, I took my first Black history class as a sophomore in college.

You're the first guest ever related to this movement, to repatriate liberated slaves back to Africa.

LIZZO: Wow.

GATES: What do you make of this?

LIZZO: I'm like, well, did they go?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: That's what I wanna know, clearly, they didn't.

GATES: Lizzo's hunch was correct.

Although the enslaved people on Nathaniel's, Virginia Plantation boarded a ship for Liberia in November of 1845.

Lizzo's ancestors are not listed on that ship's manifest.

And neither are any of the other slaves held on Nathaniel's, Mississippi Plantation.

None of them made it to Liberia.

LIZZO: Like what happened?

GATES: In 1845, Nathaniel Hugh's heirs, his son, William D. Hugh, and a minor grandson named Nathaniel Hugh Harrison, petitioned the court in Mississippi to stop the emancipation of Hugh's Mississippi Slaves, including your ancestors, they contested the will.

"This is too much money to let go."

They go, "Old man must have been out of his head."

They claim this was against the laws of the state of Mississippi, which in 1842 forbade the manumission of slaves.

LIZZO: Hmm.

GATES: In the end, the high court in Mississippi agreed with them.

So, Nathaniel slaves from his Virginia plantation ended up being transported back to Liberia.

But the Mississippi slaves, including your ancestors, remained in slavery.

LIZZO: Jesus Christ.

GATES: Now imagine.

LIZZO: I was rooting for them.

GATES: Imagine they're told that they're free.

LIZZO: Yes.

GATES: He probably said, "When I die, you all are gonna be free."

And then it snatched away.

LIZZO: Damn, that, that really, really upsets me.

GATES: Tragically, this was not the end of Lizzo's family's ordeal.

In the wake of the court's decision, Nathaniel's slaves in Mississippi were distributed among his heirs.

Lizzo's fourth great-grandparents, Ambrose and Susan, became the property of Nathaniel's son while their young daughter, Lizzo's third great-grandmother, became the property of his grandson.

LIZZO: So they were split up.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: The daughter was split up.

GATES: Yes, the family was torn apart.

LIZZO: Split from her parents.

GATES: Yes.

What's it like to see that?

LIZZO: Yeah.

It's like, I've read about this so much, and I've seen so many documentaries and films and it's, it's, it's, it's like, um, I don't, I don't, it is very uncomfortable... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: 'Cause we talk about it like slavery separated families, we say that that's what we say when we're out here talking, you know?

And it's wild to be like slavery separated my family.

GATES: Lizzo's ancestor was just eight years old when she was taken away from her parents.

And it's quite possible that she never saw them again.

Her new owner appears to have transported her to Texas, some 600 miles away, and we could find no evidence that the family was ever reunited.

LIZZO: I can only imagine, like, what, losing both of her parents like, that what that, did to her.

GATES: What do you think did to the parents?

To lose your 8-year-old daughter?

LIZZO: I think that's the fear that they lived with every day.

GATES: Mm.

LIZZO: And I feel like, I hate to say this, a part of them had to have been emotionally prepared for it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: Hardened a little bit.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: It's, there's nothing you can do to really prepare for it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: You know what I mean?

GATES: Sure.

LIZZO: It's heartbreaking, but it's like you have to keep living.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: You have to keep living.

GATES: There is a grace note to this story: when Lizzo's ancestor was taken to Texas, her parents remained behind in Mississippi.

And records show that after freedom came, her father Ambrose demonstrated that, despite all he had suffered, he was still willing and quite able to help his community.

LIZZO: "I, Benjamin Roby for and in consideration of the sum of $200 to me in hand paid, have this day bargained and sold and by these presents due grant bargain sale and convey until William Catlett, Ambrose Dangerfield and Richard Gray for the sole use and of the congregation of colored persons in the Town of Macon and Noxubee County in the state of Mississippi, known and recognized as the First African Baptist Church in said town, the 21st day of October AD 1868."

GATES: Three years after they were freed, your fourth great-grandfather, Ambrose, and two of his friends bought land for the benefit of the congregation of colored persons known as the First African Baptist Church.

(laughter).

LIZZO: Why did that make me tear up?

Of all the things we talked about today... (laughing) ...of all the things!

GATES: Isn't that amazing?

LIZZO: You got me.

Well, I wasn't expecting that.

I know that on my mother's side, um, Mama Kirkwood started a church.

GATES: Mm.

LIZZO: I didn't know on my dad's side.

I didn't know.

Whoa.

I'm actually speechless by that.

GATES: We'd already uncovered the story of Flea's grandfather Clifford Balzary, who served in the Australian army during World War I. Now moving back two generations, we came to the man who brought this line of Flea's family to Australia in the first place.

His great-great-grandfather, Albert Balzary.

Albert was born in Hungary and immigrated to Australia sometime before 1853.

While the details of his early life are unclear, we found a birth record for one of his children.

And it shows that Albert and Flea shared something profound.

FLEA: "Births in the colony of Victoria.

When, and where born July 21st, 1858.

Pleasant Creek, child's name, Arthur Vincent Balzary, father Albert Vincent Balzary, Rank or Profession, gold digger and musician."

Gold digger and musician.

GATES: Did you have any idea that you were not the first musician on the Balzary line?

FLEA: I had no idea; I had never heard that before.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

FLEA: Amazing, I love it.

GATES: Unfortunately, Albert's musical talents were eclipsed by a more urgent need.

The need to earn a living.

When he arrived in Victoria, the province was in the throes of a gold rush.

And immigrants from all over the world were pouring in, searching for riches that almost invariably proved elusive.

Albert was not an exception.

He found no riches, just long hours of hard work in brutal conditions.

And when the gold rush petered out, he paid the ultimate price for his efforts.

FLEA: "Age 51 years.

When and where died?

Third July, 1865.

Dunolly Hospital.

Cause of death, duration of last illness, dysentery, five months."

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: Well, dysentery, is that a, is that a... GATES: Intestines.

FLEA: Intestines.

GATES: Severe diarrhea.

FLEA: Severe diarrhea.

GATES: You die of dehydration.

FLEA: You die of dehydration.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: And living a hard life will do that to you, man.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: You know, out there digging in the dirt and probably whatever mining he did after that, like, I mean, when gold rush didn't pan out, he must have done other types of mining... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: ...because that's what he knew how to do.

GATES: Right.

FLEA: Um, it's sad, you know?

GATES: When Albert died, he left behind a wife, Flea's great-grandmother, a woman named Henrietta Balzary.

She was just 32 years old, and suddenly she had to raise a family all on her own.

She had four children by this time, Flea.

FLEA: 32 with four kids.

GATES: Four children and a widow.

FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: So let's see how she fared.

FLEA: Okay.

GATES: Please turn the page.

The two documents in front of you are from the year 1870 and 1872.

Five and seven years after Albert's death.

Would you please read the transcribed section of both?

FLEA: "Petty sessions at Dunolly on Friday, the 23rd day of September, 1870, complainant William Crofton, defendant Henrietta Balzary.

Cause, selling ale without license.

Petty sessions at Dunolly, on the 3rd day of September, 1872, defendant Henrietta Balzary.

Cause selling liquor without license.

Decision, defendant fined five pounds with one pound, six shillings costs."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: So she was selling probably some kind of bootleg to make do.

GATES: You got it.

FLEA: Wow.

GATES: Yeah, what do you make of that?

FLEA: I, you know, you gotta do what you gotta do to get by, you know?

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: I, I appreciate the, uh, the, the industriousness of doing it.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: You know, power to her man.

GATES: Henrietta may have been industrious, but she faced steep odds.

Australia did not offer many avenues for a single mother to make a living.

Most experienced dire poverty, and selling alcohol illegally was one of the few ways to survive.

Fortunately, Henrietta soon found another.

FLEA: "Marriages solemnized in the district of Dunolly."

She really didn't get outta Dunolly.

"March 11th, 1875, William Lovett, bachelor.

Profession, minor, age 43.

Henrietta Balzary, widow, profession storekeeper."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Age 42.

GATES: Henrietta went from illegally selling booze to becoming a storekeeper, presumably with a license now.

FLEA: Yes.

GATES: And she got married again.

FLEA: To another minor.

GATES: Your ancestor had to be incredibly scrappy and resourceful.

FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: You see any of these circumstances, Mr.

Flea in yourself?

FLEA: Uh, very much so.

Yeah.

I'm scrappy and resourceful.

GATES: As it turns out, Henrietta had been living by her wits for far and longer than Flea even imagined, as evidenced by the manifest of the ship that brought her to Australia.

A teenage girl from Ireland, utterly alone in the world.

FLEA: "List of immigrants per ship Pemberton arrived on the 14th, May, 1849.

Female orphans."

Wow.

"Name Honora Bentley, age 16, calling, house servant.

Native place and county Limerick, Ireland.

Read or write?

Both."

So she was an orphan.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: And her aspiration was to be a house servant.

GATES: Yes.

FLEA: That was her hope... GATES: That's right.

FLEA: ...that she could do that.

She could read and write.

It's a trip, man.

That's my people.

GATES: There was one more beat to this story.

Records show that Henrietta was born around 1833 in County Limerick, Ireland.

Which means that when she was roughly 12 years old, she was caught up in what we now call The Great Famine.

A cataclysm that claimed the lives of roughly a million Irish people.

County Limerick alone saw its population fall by close to 70,000 people in just 10 years.

We don't know what happened to Henrietta during the famine, or to her parents, but by the time she was 16, she was an orphan living in a workhouse.

She was all on her own.

FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: Had to be very hard.

Had to be really hard.

I, you know, kind of mean, I wonder how long she had been an orphan when she was in the workhouse and... FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: We don't know or why.

FLEA: She might have been on an orphan since birth.

GATES: She could have been.

FLEA: You know what I mean?

She could have been abandoned at birth.

She could have been, they could have died of starvation, and they could have... GATES: She could have been illegitimate.

I mean, we don't know.

FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: We just don't know.

FLEA: Yeah.

GATES: The workhouse where Henrietta found herself was basically a walled-off factory with beds.

Once inside, she likely had to do physically demanding labor in exchange for food and shelter.

It's little wonder that she was willing to roll the dice and take a risk on Australia, knowing nothing of what was to come.

Do you see any of her bravery and resilience in yourself?

FLEA: Um, I hope so.

You know, it makes me feel like, you know, sometimes I've, you know, all my tough times I had and stuff makes, I feel like I had it pretty easy, you know?

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: I mean, I always, even when I was like skipping the bill at restaurants and running out without paying, I was eating, you know what I mean?

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: And people starving to death, it's serious business, you know?

GATES: What do you think of your great-great-grandmother, and what's it like for you to think that you descend from her?

FLEA: Um, I love it.

I think she's amazing.

Um, you know, she, she did what she had to do to survive.

And I'm sure that so much of it just comes from love and caring, not only, you know, for herself and treasuring life itself, and not just becoming, uh, not dissipating... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: ...at any point, you know?

Um, but continuing to focus on doing what she could do to make life good for herself.

And, you know, remarrying, she, so she, you know, I hope the guy was nice.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: You know, I hope they're all nice to her.

I hope Albert was nice to her.

GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: I hope this other guy is nice to her, too.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: Um, 'cause it must have been real hard.

GATES: Does it make you look at your own success any differently?

FLEA: You know, I've always had a real intense striving, and there's a part of me that's like, you know, like a part of me that performs and stuff where I push myself to beyond where I should push myself.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: You know, I push myself to like, just like practically death, you know what I mean?

I go back to the hotel and, you know... (makes sound) ....because I push myself so hard when I perform.

And, um, it makes me feel like that that's in me.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FLEA: That survival thing, like I really have it... GATES: Right.

FLEA: ...deeply ingrained in me.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for each of my guests; it was time to show them their full family trees.

LIZZO: Wow.

(laughter).

GATES: Now filled with names they'd never heard before.

These are all of the ancestors... For each, it was a moment of wonder offering, a glimpse of the women and men who'd sacrificed so much to lay the groundwork for their success.

FLEA: Man, I gotta process it.

I gotta think about it.

I got; it's really given me something to chew on and meditate on.

It's a lot.

I, I feel all of it, like in my body... GATES: Yeah.

FLEA: ...like in my psyche and who I am.

GATES: That's great.

FLEA: And it connects.

LIZZO: It's these little things, this whole tree just shows me like, the smallest things have had to happen for me to be sitting here today.

GATES: Absolutely.

LIZZO: I mean, so many things... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: ...had to have gone, right?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LIZZO: And I'm glad they did.

They were put in slavery, they were separated, they... (sighs).

And I'm still here.

This is, I am here for them, this is their resilience, I'm the proof of it.

GATES: And you're going strong.

LIZZO: And I'm going strong, baby.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Lizzo and Flea.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep7 | 30s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. introduces musicians Flea and Lizzo to their inspiring ancestors. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: